Collider hopes for a 'super' restart

- Published

Discovery of the new particle would herald a new realm of physics, as the BBC's Pallab Ghosh reports

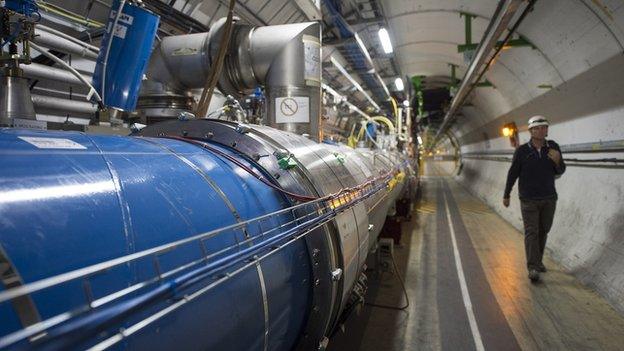

A senior researcher at the Large Hadron Collider says a new particle could be detected this year that is even more exciting than the Higgs boson.

The accelerator is due to come back online in March after an upgrade that has given it a big boost in energy.

This could force the first so-called supersymmetric particle to appear in the machine, with the most likely candidate being the gluino.

Its detection would give scientists direct pointers to "dark matter".

And that would be a big opening into some of the remaining mysteries of the universe.

"It could be as early as this year. Summer may be a bit hard but late summer maybe, if we're really lucky," said Prof Beate Heinemann, who is a spokeswoman for the Atlas experiment, one of the big particle detectors at the LHC.

"We hope that we're just now at this threshold that we're finding another world, like antimatter for instance. We found antimatter in the beginning of the last century. Maybe we'll find now supersymmetric matter."

The University of California at Berkeley researcher made her comments at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science., external

In the debris

Supersymmetry is an addition to the Standard Model, which describes nature’s fundamental particles and their interactions.

Susy, as it is sometimes known, fills some gaps in the model and provides a basis to unify nature's forces.

It predicts each of the particles to have more massive partners. So the particle that carries light – the photon – would have a partner called the photino. The quark, the building block of an atom’s protons and neutrons, would have a partner called the squark.

But when the LHC was colliding matter at its pre-upgrade energies, no sign of these superparticles was seen in the debris, which led to some consternation among theorists.

Now, with the accelerator about to reopen in the coming weeks, there is high hope the first evidence of Susy can be found.

The machine is going to double the collision energy, taking it into a domain where those theorists say the gluino really ought to emerge in sufficient numbers to be noticed. The gluino is the superpartner of the gluon, which "glues" the quarks together inside protons and neutrons.

The LHC’s detectors would not see it directly. What they would track is its decay, which scientists would then have to reconstruct.

But importantly, those decay products should include the lightest and most stable superparticle, known as the neutralino – the particle that researchers have proposed is what makes up dark matter, the missing mass in the cosmos that gravitationally binds galaxies together on the sky but which cannot be seen directly with telescopes.

"This would rock the world,” said Prof Heinemann. "For me, it’s more exciting than the Higgs."

'The other side'

So, not only would supersymmetry proponents be elated because they would have their first superparticle, but science in general would have a firm foot on the road to understanding dark matter.

Dr Michael Williams, from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said: "We sometimes talk about the dark matter particle, but it’s perfectly plausible that dark matter is just as interesting as [normal] matter, [which] has a lot of particles that we know about.

"There might be just as many dark matter particles, or even more.

"Finding any particle that could be a dark matter candidate is nice because we could start to understand how it affects the galaxy and the evolution of the universe, but it also opens the door to whatever is on the other side, which we have no idea what is there."

Particle physicists have three major conferences in August and September, one of which is the main gathering of the supersymmetry community. All these meetings are bound to draw huge interest.

But Prof Jay Hauser, who works on the CMS detector at the LHC, added a little caution on timings. "Even if we did see something, remember it might be complicated enough that it takes us a while to explain it," he told reporters.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk an follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published10 July 2014

- Published1 July 2014

- Published18 February 2014