Google machine learns to master video games

- Published

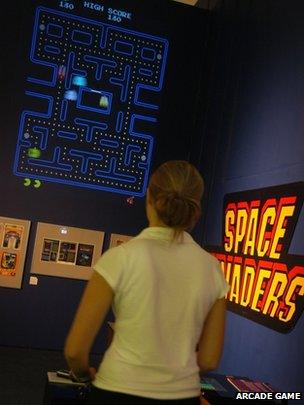

The machine learned to play video games and sometimes performed better than human professional players

A machine has taught itself how to play and win video games, scientists say.

The computer program, which is inspired by the human brain, learned how to play 49 classic Atari games. In more than half, it was as good or better than a professional human player.

Researchers from Google DeepMind said this was the first time a system had learned how to master a wide range of complex tasks.

The study is published in the journal Nature, external.

Dr Demis Hassabis, DeepMind's vice president of engineering, said: "Up until now, self-learning systems have only been used for relatively simple problems.

"For the first time, we have used it in a perceptually rich environment to complete tasks that are very challenging to humans."

Dr Demis Hassabis shows how the AI taught itself to excel at Breakout

Technology companies are investing heavily in machine learning. In 2014, Google purchased DeepMind Technologies for a reported £400m.

This is not the first time that a machine has mastered complex games.

IBM's Deep Blue - a chess-playing computer - famously beat the world champion Garry Kasparov in a match staged in 1997.

However, this artificial intelligence system was pre-programmed with a sort of instruction manual that gave it the expertise it needed to excel at the board game.

The machine excelled at Space Invaders but Pac-Man was harder work

The difference with DeepMind's computer program, which the company describes as an "agent", is that it is armed only with the most basic information before it is given a video game to play.

Dr Hassabis explained: "The only information we gave the system was the raw pixels on the screen and the idea that it had to get a high score. And everything else it had to figure out by itself."

The team presented the machine with 49 different videogames, ranging from classics such as Space Invaders and Pong, to boxing and tennis games and the 3D-racing challenge Enduro.

In 29 of them, it was comparable to or better than a human games tester. For Video Pinball, Boxing and Breakout, its performance far exceeded the professional's, but it struggled with Pac-Man, Private Eye and Montezuma's Revenge.

"On the face it, it looks trivial in the sense that these are games from the 80s and you can write solutions to these games quite easily," said Dr Hassabis.

"What is not trivial is to have one single system that can learn from the pixels, as perceptual inputs, what to do.

"The same system can play 49 different games from the box without any pre-programming. You literally give it a new game, a new screen and it figures out after a few hours of game play what to do."

The research is the latest development in the field of "deep learning", which is paving the way for smarter machines.

Scientists are developing computer programs that - like the human brain - can be exposed to large amounts of data, such as images or sounds, and then intuitively extract useful information or patterns.

Examples include machines that can scan millions of images and understand what they are looking at: they can tell a cat is a cat, for example. This ability is key for self-driving cars, which need an awareness of their surroundings.

Or machines that can understand human speech, which can be used in sophisticated voice recognition software or for systems that translate languages in real-time.

Dr Hassabis said: "One of the things holding back robotics today, in factories, in things like elderly care robots and in household-cleaning robots, is that when these machines are in the real world, they have to deal with the unexpected. You can't pre-program it with every eventuality that might happen.

"In some sense, these machines need intelligence that is adaptable and they have to be able to learn for themselves."

Some fear that creating computers that can outwit humans could be dangerous.

In December, Prof Stephen Hawking said that the development of full artificial intelligence "could spell the end of the human race".

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published19 December 2013

- Published2 December 2014

- Published2 October 2014

- Published27 January 2014