How do you solve a problem like the 'Beefalo'?

- Published

When bison were cross-bred with domestic cattle, a hybrid dubbed the "Beefalo" was spawned. But the creatures escaped and are now causing environmental havoc in The Grand Canyon. Some want a cull, but is this the best way to deal with the animals?

There is a strange hybrid creature - an alien, the result of a failed breeding programme - causing havoc in the Grand Canyon.

Its destructive ways are alarming both environmentalists and Native American groups who want it removed, yet tourists find it so intriguing they're putting their lives at risk to catch a glimpse.

So just how do you solve a problem like the "Beefalo"?

Out on the canyon's North Rim it's estimated that at least 600 beefalo - a crossbreed of bison and domestic cattle - are roaming.

This thirsty beast can consume 10 gallons each per trip to a watering hole, which means they can drink a source dry in no time.

But the animals' environmental impact doesn't stop there. They also defecate at the watering holes and their hefty weight compacts the soil.

Their leisurely dust baths and healthy appetites leave the ground bare.

The Grand Canyon National Park is a huge tourist attraction, drawing millions of visitors each year

While they wallow, other animals are pushed out and the ecosystem is thrown out of balance, say environmentalists. Insects and rare plants are affected along with the habitat.

Martha Hahn, science and natural resources manager at Grand Canyon National Park took us to Little Park Lake, one of the key water sources, to show us the damage.

"When we're looking at 2-300 bison using this one water source, they can drink it dry pretty quickly," she told BBC Radio 4's Costing the Earth programme.

"In terms of what could be here, 80% of our vegetation and other species rely on these very limited water sources. Lakes like this in the park and surrounding area - there are probably seven in total.

Beefalo in the Grand Canyon

"If they're depleted in terms of water those other species will be affected."

Tom Sisk from the University of Northern Arizona has been studying the effects by fencing off half the grazing area but the mighty beefalo have simply broken down the fences.

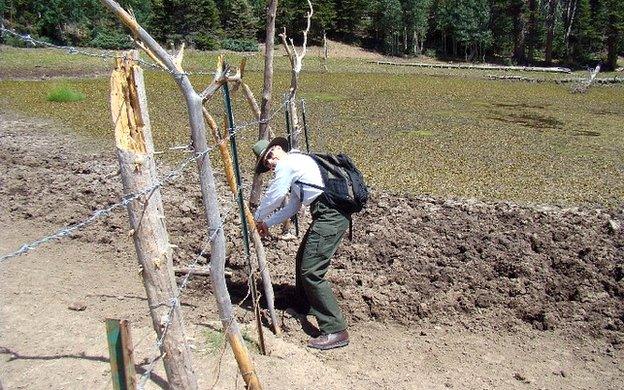

The animals are causing extensive damage at some of the Park's valuable water sources

Martha Hahn fixes beefalo damage to a fence. Barbed wire poses no obstacle to the mighty beasts

Six hundred may not seem many in the massive expanse of the Grand Canyon but as a herding animal their impacts are being concentrated around the most sensitive areas.

However Native American groups, for whom the canyon is a spiritual home, have also seen ancient ruins destroyed as the animals rub along the stone structures.

We'd factored in a whole day's hiking to search for the beefalo as they herd together and can move great distances. But we couldn't have been more surprised when we came across hundreds right near the park entrance, just alongside the road.

"It's quite amazing. Frankly I've never seen this many bison in one view in all the years I've worked here." Tom Sisk told us.

"It was just a few years ago people were writing stories about the 'ghost bison' of the Grand Canyon. They'd go out for days and see the impacts but never see an animal. So we really are seeing a dramatic increase in the population size."

Conservationists say beefalo numbers have exploded in recent years

The animals were the result of a failed breeding experiment to produce a hardy, commercial animal

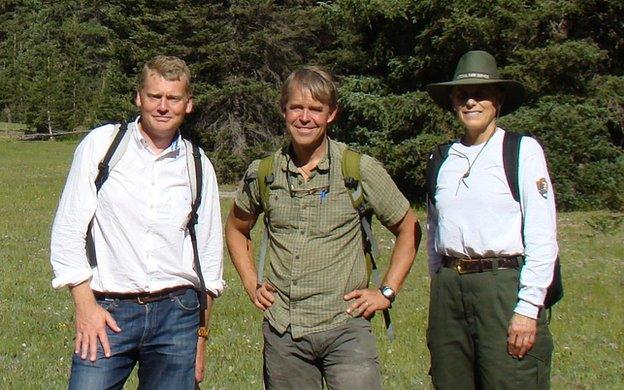

Costing the Earth presenter Tom Heap (L) was given a tour of beefalo sites by Tom Sisk and Martha Hahn

Tourists also stop to get pictures - some taking more risks than others.

"We're getting around an accident a day," Martha told us, "if a car gets in the viewshed between a calf and its mother she will ram the car. Drivers have also accidentally hit animals on the road at night."

It was Charles "Buffalo" Jones who started breeding the animals in 1906. At the time, bison - an iconic animal - were low in numbers and he crossbred them with domestic cattle to produce a hardy, commercial animal.

When he gave up, the remaining animals were managed by the state and numbers controlled by limited hunt licences. However when the animals ventured into the National Park, where hunting is banned and no natural predators exist, their numbers started swelling - by an estimated 50% a year.

Officially a 'beefalo' is a registered breed of cattle crossbreed with a specific percentage of bison. But locally tourists refer to the beasts in the park as beefalo even though they look and lean more towards bison in appearance and genetics.

The animals do venture outside the park boundary in the closed season (when hunting is banned), and Martha Hahn even thinks they may have learnt when the hunting season starts and ends.

"The first shot they hear they'll move. The lead one will know and you'll see that one heading out and the rest of its herd - 200 plus - following in a line, some of them even running," she explains.

Other hybrid animals

Liger - The liger is the result of a cross between a male lion and a female tiger, and occur only in captivity. They are the biggest of all big cats, reaching lengths of up to 3.5m.

Pizzly bear - Also known as a grolar bear, it is the progeny of a polar bear and a grizzly bear. Examples exist in captivity and in the wild - in areas where the species' ranges overlap, such as the Canadian Arctic

Africanised honey bees - They came about in the 1950s when European and African honey bee sub-species were cross-bred to boost tropical hardiness. But the aggression with which hybrids guard their hives earned them the sobriquet "killer bees".

The authorities have been consulting on the best way to deal with the animals. While some hunters would readily add such a beast to their tally, many Native American groups are opposed to killing for sport.

The options include lethal but also non-lethal methods: corralling, herding or administering contraception. But any efforts have to be effective, raising the issue of who receives any surviving animals.

Some have suggested tribes that have traditionally lived alongside bison should benefit to help pass on cultural traditions, but other parties including media mogul and ranch owner Ted Turner have also offered assistance.

Any control measures won't take place until next year but in the meantime, the numbers grow, tourists flock and the damage continues.

You can hear more about the beefalo on Costing the Earth on BBC Radio 4 Tuesday (3rd March) at 15:30 or Wednesday (4th March) at 21:00.

- Published26 January 2014

- Published8 July 2014