Penguin waddle put to the test

- Published

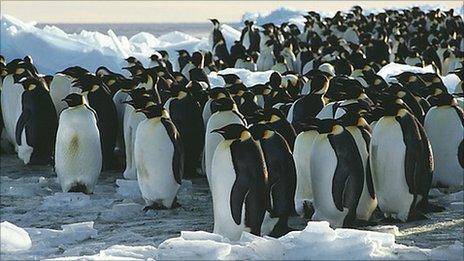

A penguin's waddle is one of nature's weirdest walks

"Come on Puddle… You can do it!" yells Prof John Hutchinson.

Puddle - a Humboldt penguin - seems more than a little bemused.

And with good reason.

A team of scientists have come to Penguin Beach at London Zoo, installed a hi-tech track and are now trying to lure Puddle and his penguin pals across it.

"Go Puddle, go!" encourages Prof Hutchinson, from the Royal Veterinary College (RVC).

And at last - with a fishy treat to help him along the way - the little bird waddles along the runway.

It is this distinctive walk that scientists from RVC and University of Texas at Austin are here to study.

Beneath the track lie force plates loaded with sensors, which allow the researchers to analyse how these birds get around.

"Penguins move in a really weird way," explains Prof Hutchinson.

"They have a very upright posture like a human, but they also have very short, crouched legs - it is very comical."

Prof John Hutchinson on the eccentricity of the penguin's walk

He adds: "But when I see an animal do something weird, as an evolutionary biologist, I want to know how that evolved, how it got that way.

"And with these experiments, we're trying to tie what we know about penguin evolution with penguin physics."

Foot swing

Previous studies of the penguin's ungainly gait have revealed that the waddle is in fact the most energy efficient way for them to get about on land.

But these experiments will reveal exactly how they are doing this.

"They are applying forces left and right as they swing their bodies from side to side," says Prof Hutchinson.

"But what is not known about penguins is how the legs do that, how big are the sideways forces on penguin legs and how that compares to other waddling birds.

"And that's why we need these force platforms to measure the forces in the legs individually."

The Waimanu is one of the oldest penguins discovered - and most likely had a more horizontal posture

But it turns out that penguins didn't always waddle. Fossils reveal that their ancient ancestors moved in a different way.

"We have all kinds of fossils as far back as 60 million years ago from the Southern Hemisphere," says palaeobiologist James Proffitt, who has come from Texas to study the birds.

"That gives us a chance to understand how these unusual anatomies and behaviours have evolved in deep time and how we have all these bizarre things we see today."

The bird bones show that the first penguins were a varied bunch: some were tiny, but others grew as tall as humans, hunting large fish with their spear-like beaks.

James Proffitt is particularly interested in a genus of penguins known as Waimanu.

These birds, unearthed in New Zealand, are the oldest-known penguins, living between 58-60 million years ago.

Mr Proffitt explains: "We know that penguins such as Waimanu were also flightless, wing-propelled divers based on things like their wing proportions and their relative size.

"But in many ways they were different, and they probably moved about differently on land based on the anatomy of their legs and hip bones."

The team believes that these proto-penguins had a more horizontal posture, and their walk would have looked similar to that of a modern-day albatross.

Today's penguins most likely evolved their unusual anatomy and resulting waddle as they became better and better adapted to swimming.

As their body shape changed to help them fly through the water with ease, they became more and more clumsy on land.

Penguins use their wings to fly through the water

Back at the running track, and the penguins seem to be enjoying not quite doing what they are told.

But Zuzana Matyasova, London Zoo's deputy team leader for the bird department, has found a way to attract their attention.

A combination of some dangling string, a tennis ball on a stick - or some fish - is proving hard for some penguins to resist.

"Some of the youngsters are really inquisitive: anything new in their enclosure is almost like a challenge and they want to be the first ones to try it out," she explains.

She's hoping all this hard work will shed light on these birds.

"I work with them every day, and I wonder about their way of moving - their distinctive waddle is just amazing."

While not every bird fancies taking a waddle down the runway, after several days, the scientists manage to collect enough data to begin their analysis.

And by comparing this with their studies of ancient penguins, they hope to establish how and when one of nature's most distinctive walks evolved.

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published4 November 2014

- Published2 June 2011

- Published9 February 2013