What next for the Large Hadron Collider?

- Published

The scene is set for a new kind of physics: a new theory that will be the biggest change in our thinking for 100 years

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) has been restarted after a two-year shutdown.

Physicists hope it could lead to discoveries that could potentially represent the biggest revolution in physics since Einstein's theories of relativity.

Among them is Prof Jordan Nash from Imperial College London, who is working on the CMS experiment, external at the LHC.

"We are opening a new window on the Universe and looking forward to seeing what's there," he said.

"As much as we have a lot of theories of what might be out there we don't know. We'd love to find something completely unexpected and we might, and that's the exciting bit."

Why are scientists doubling the LHC's energy?

They want a glimpse into a world never seen before. By smashing atoms harder than they have been smashed before physicists hope to peel back another veil of reality.

The aim of the various theories of physics is to explain how the Universe was formed and how the bits that make it up work.

One of the most successful of these theories is called the "Standard Model", external.

It explains how the world of the very, very small works.

Just as the world became very strange when Alice shrunk after drinking a potion in the children's book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, physicists have found things are quite different when they study the goings on at scales that are even smaller than the size of an atom.

By doubling the energy of the LHC, it will enable them to discover new characters in the wonderful and mysterious tale of how the Universe works and came to be.

What is the Standard Model?

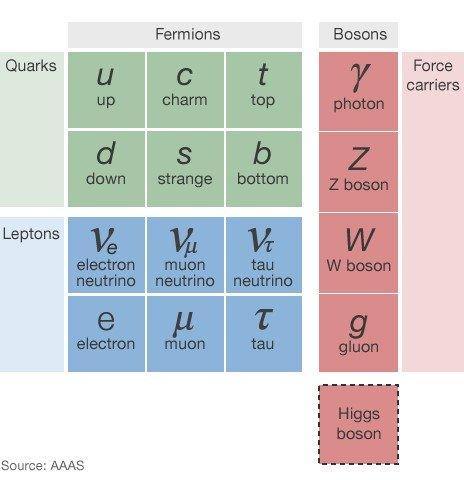

The Standard Model describes how the basic building blocks that make up atoms and the forces of nature interact.

And just as in Alice's stories it features some eccentric characters, notably a family of 17 elementary particles.

Some are familiar from school physics lessons, household names if you like.

One of the best known in the sub-atomic world is perhaps the electron, which orbits the atom and is involved in electricity and magnetism.

Another flashy A-lister is the photon, which is a particle of light.

But most particles from the Standard Model family are more niche, a little more art house if you like, and have strange names.

The elementary particles that make up the world around us. The Standard Model was thought to explain nearly everything. Now, it seems, it is time for an upgrade.

In fact, one of them is actually called "the strange quark".

And others from this group of particles are named as if by thoughtless and unimaginative parents: "up", "down", "top" and "bottom" though "charm" does sound a little more, well, charming.

A couple of these combine in various ways to form protons and neutrons, which along with electrons make up atoms from which the world is made. These are all members of a group called "fermions".

And there is another group called the "bosons", that quite literally hold the place together.

They are called the "force carriers" in physics text books and give rise to the forces of nature: electrical, magnetic and nuclear forces, which pull other particles together or push them apart.

With the discovery, external of the sub-atomic world's biggest celeb of all, the Higgs boson, scientists have now detected all the particles predicted by the Standard Model: a theory that beautifully explains how the Universe works in intricate detail.

Or so scientists thought.

What is wrong with the Standard Model?

It is incomplete. For a long time physicists thought that their Standard Model theory could explain almost everything.

Then came two phenomena that showed that it explained hardly anything.

First was the observation that galaxies are rotating much more quickly than they should.

The faster a galaxy rotates the more material it contains.

The observations suggested that they contain five times more material than could be detected.

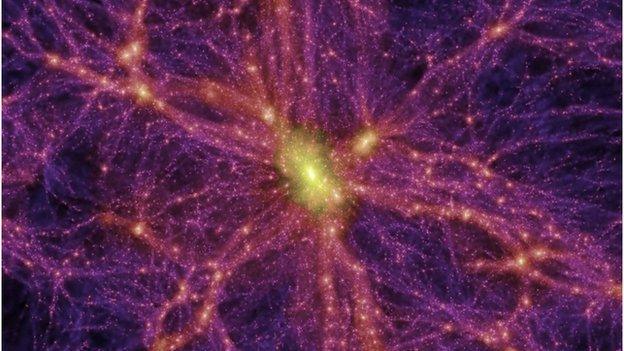

Computer-generated image of dark matter shown in pink. It is the invisible scaffold on which the Universe hangs yet it cannot be explained by the Standard Model

This invisible material has been called "dark matter", external which physicists believe accounts for a quarter of the Universe.

Second was the observation that galaxies were accelerating apart from each other driven by an even more mysterious force that the researchers who discovered it called "dark energy", external.

So all in all the Standard Model, brilliant though it is at explaining how our tiny corner of the cosmos works can't account for how the remaining 95% of the Universe works.

Even then, of the 5% it is good for it can't explain gravity.

And, just as the erstwhile poster child of physics slinks off to find a place to curl up and quietly weep, comes the biggest humiliation of all: it can't explain why the Universe exists at all.

Shortly after the Big Bang there were equal amounts of matter, from which all the atoms, stars and planets are made and anti-matter.

Moments later the two should have cancelled each other out, as ripples sometimes do when meeting in a pond, to create a gigantic blast of energy and then, nothing but light.

Our very existence demonstrates that clearly this did not happen.

You might have thought that this was bad news for physics - but actually physicists such as Prof Nash couldn't be more excited.

"It's our biggest opportunity in a generation to find out what's the next step, where do we go from here and how do we explain the things we don't understand about the composition of the Universe."

Will the LHC lead to a new theory of physics?

That is what physicists are hoping for. With the Large Hadron Collider set to double its energy, physicists hope that they will discovery weirder and even more wonderful particles that will point the way to a new more complete theory of sub-atomic physics.

In other words a sequel, with new even more bizarre characters and with no doubt some twists and turns in the plot.

Book two has the working title of: "Beyond the Standard Model".

Scientists hope to find evidence of the invisible "stuff" called dark matter: the unseen Cheshire Cat behind the grin of the visible Universe we see around us.

There are lots of different theories for what the cat might look like.

Among them is an idea called supersymmetry or "Susy" for short.

This idea predicts new particles that are invisible partners of the ones we know already about.

One of these could be dark matter.

Another idea is that dark matter could be explained by the wonderfully evocatively named "dark sector".

This comprises shadowy new particles that don't obey the same forces as everything else but cannot easily be detected. They might be the invisible culprits that have been making our galaxies rotate faster than they should.

Researchers will also be looking to find particles that are manifestations of extra-dimensions that we cannot detect but are predicted in some theories that extend the Standard Model to incorporate gravity.

And the LHCb experiment, external will be studying the differences between matter and anti-matter in unprecedented detail.

What's next?

Who knows, but possibly one of the biggest changes in thinking in physics for 100 years.

Researchers, such as Prof Tara Shears of Liverpool University who is working on the LHCb experiment hope to have their first taste of so-called "new physics: a set of discoveries that will radically transform the theories of physics and our knowledge of how the Universe works.

"If I could have just one outcome form the next run of the LHC this would be it," she explained with a far away look in her eyes.

"It would be to make a discovery so unexpected that it doesn't fit with any of our theories, something that would show us that we have been on the wrong track in our efforts to understand the way that the forces of nature work, the way that matter is composed, something that will knock our heads sideways to make us come from a new direction.

"And that would be the paradigm shift and that shift, in my dreams would lead us to a much deeper understanding of the Universe.

"It would be wonderful if we could make a head start that would point us in the right direction."

The sub-atomic world is set to become "curiouser and curiouser".

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external