Zombie worms ate plesiosaur bones

- Published

Osedax worms eat the bones of dead whales on the ocean floor

A type of deep-sea worm that eats whale bones has existed for 100 million years and may have chewed up chunks of the fossil record, a study suggests.

Researchers found bore-holes indicative of Osedax worms in the fossilised flipper of a plesiosaur, and the rib and shell of an ancient sea turtle.

This implies that these scavengers, also known as zombie worms, may have influenced which fossils remain today.

The research appears in the Royal Society's journal Biology Letters, external.

"Our discovery shows that these bone-eating worms did not co-evolve with whales, but that they also devoured the skeletons of large marine reptiles that dominated oceans in the age of the dinosaurs," said the study's co-author Dr Nicholas Higgs, a researcher at Plymouth University's Marine Institute.

"Osedax, therefore, prevented many skeletons from becoming fossilised, which might hamper our knowledge of these extinct leviathans."

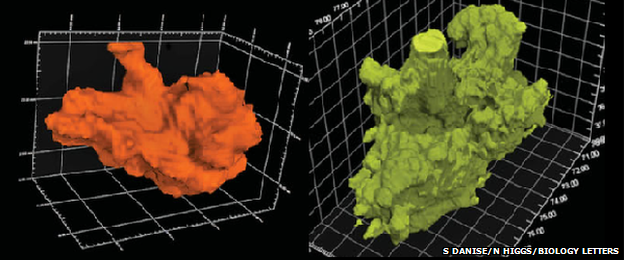

The researchers used CT scans to compare the shape of worm borings

This family of worms, first discovered by a deep-sea robot, external off the California coast in 2002, makes its living from corpses that fall onto the seafloor. They have been found at depths of up to 4km.

As adults, the finger-length worms have no mouth or digestive system. Instead they burrow into bones using root-like tendrils, which they use to drink up the fatty molecules they need to survive.

Destructive influence

It was previously thought that they had co-evolved with whales, whose graveyards they often call home at the bottom of today's oceans.

But the new research suggests zombie worms must have been around much earlier - 100 million years ago, in fact, when huge plesiosaurs roamed the deep. Then when those huge reptiles died out, 66 million years ago, they made do with sea turtle corpses until whales emerged another 20 million years later.

The evidence that positions Osedax worms firmly inside the plesiosaur corpse is the cavities they left behind. Dr Higgs and his colleague Silvia Danise made detailed 3D scans of two bore-holes left in the plesiosaur's flipper bone, along with four from the sea turtle skeleton.

They closely match the borings left in modern whale bones.

The worms may have eaten away the bones of plesiosaurs like the liopleurodon

As well as implying that these deep-sea zombie worms have a long and hungry history, the findings suggest that the scavengers may have consumed whole bones and skeletons before they became fossils - leaving holes not just in the bones that are left, but in our fossil record of the oceans.

"The increasing evidence for Osedax throughout the oceans past and present, combined with their propensity to rapidly consume a wide range of vertebrate skeletons, suggests that Osedax may have had a significant negative effect on the preservation of marine vertebrate skeletons in the fossil record," said Dr Danise, who has now moved from Plymouth to the University of Georgia in the US.

"By destroying vertebrate skeletons before they could be buried, Osedax may be responsible for the loss of data on marine vertebrate anatomy and carcass-fall communities on a global scale."

Related topics

- Published13 May 2014

- Published14 August 2013

- Published9 September 2012

- Published3 June 2011