Voyage to the north through ramparts of ice

- Published

- comments

Nansen wanted to jam a ship into the ice and let drift do the rest

At first sight the great slabs of grey-blue ice covering the Arctic Ocean appear to be rock-solid and immobile but the extraordinary fact is that they are restless and shifting.

Beneath what appears to be an unbending and endless landscape, the winds and currents are constantly at work reshaping it.

During the long dark months of the past winter, Norway's research vessel, the Lance, has been stationed amid the floes and drifting with them at the amazing speed of half a mile an hour.

In the few days I spent on board, when the vessel seemed to be locked in a vice-like grip, we actually travelled about a dozen miles.

The view was essentially unchanging but the satellite navigation system revealed the extent of the drift and the Lance's journey can be seen here, external.

Although deploying the latest technology, the expedition's use of ice drift is not an original idea but instead draws on the proud legacy of one of the greatest ventures in polar discovery more than a century ago - the voyage of a vessel known as the Fram under its leader, Fridtjof Nansen.

Nansen wanted to test what was then an unthinkable notion - jamming a ship into the ice and letting the flow of the ice do the rest.

Go with the floe

He and others had noticed that old timbers from northern Russia were washing up several thousand miles away on the shores of Greenland - and the only possible explanation was that winds and currents had carried them there. Scientists now call this feature as the Transpolar Drift.

And when an American vessel, the Jeannette, was crushed in the ice off Siberia in 1881, there was huge surprise when identifiable parts of the wreckage also turned up in Greenland.

That led Nansen to dream up the idea of using the natural mobility of the ice to achieve something that was impossible at the time - to penetrate what he called the "ramparts of ice" and reach the North Pole.

The movement of the ice, he judged, was sometimes "so strong and rapid as to equal that of a ship running before the wind".

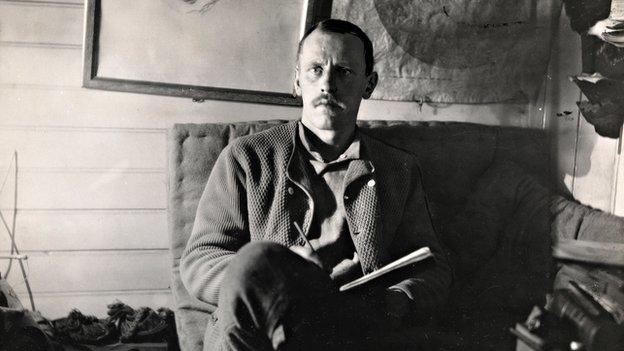

Fridtjof Nansen believed that working with the forces of nature would pull the expedition through

Nansen concluded that a vessel of the right shape - with a tough rounded hull - would be squeezed upwards as the ice closed around it, and be lifted above the surface to avoid destruction.

"I believe that if we pay attention to the actually existent forces of nature, and seek to work with and not against them, we shall thus find the safest and easiest method of reaching the Pole," he wrote.

"The ship will simply be hoisted up and will ride safely and firmly…the current will be our motive power, while our ship, no longer a means of transport, will become a barrack."

Initially, his concept was met with derision. In 1892, when he outlined his plan to the Royal Geographical Society in London, the big names of polar exploration lined up to dismiss it.

Dire warnings

The legendary figure of Admiral Sir Leopold M'Clintock, who had led the first expedition through the fabled North West Passage in the Canadian Arctic, warned Nansen that "the danger of being crushed in the ice was too great."

Sir Allen Young, another giant of Arctic discovery, highlighted the fact that no one knew whether land or islands lay in the unknown reaches of the Far North and that the idea of drifting would be "extremely dangerous".

The American explorer General Greely went even further, warning that the expedition would fail with the risk of "suffering and death among its members".

In 1893, when Nansen and his team set off, the growth of winter ice quickly surrounded the Fram and the moment of truth arrived. The ice floes jostled around the ship and a loud creaking began.

"Now both pressure and noise gets worse and worse; the ship shakes, and I feel as if I myself were being gently lifted with the stern-rail, where I stand gazing out at the welter of ice-masses that resemble giant snakes writhing and twisting their great bodies out there under the quiet starry sky."

Other explorers warned that the crew risked suffering and death through their bold endeavour

The theory worked. The Fram rose, and its well-built frame and multi-layered hull withstood what no one other vessel had managed before.

The result was that for three years the ship inched generally northwards and westwards, sometimes driven back, sometimes stationary, but proving that the Arctic is an active, restless region.

The ship did not make it to the Pole so Nansen and a crewmate ventured towards it on foot and attained the previously-unheard of latitude of 86 degrees North, where massive ridges of ice blocked their path.

The two of them, and the Fram, returned safely, and Nansen became an instant hero. Norway witnessed the largest gathering of people ever seen at that moment in its history, a significant moment for a country then yearning for its independence from Sweden.

And in the years that followed, Nansen emerged as the essential expert for others to consult before any major expedition. His fellow Norwegian, Roald Amundsen, the first man to reach the South Pole, and the British explorers Scott and Shackleton, all went to see him.

No escape

So how have things changed since Nansen's day?

The Lance is built of steel rather than the wood used for the Fram but it has the same rounded shape which serves the same purpose.

On one occasion last February, the Lance's bow rose nearly a metre into the air as the ship was lifted by an underwater ice-floe. And during our stay I felt a slight tilt as that process was at work again.

The scientists on the Lance are measuring everything from the weather to the ice to the creatures beneath it. Nansen, with cruder instruments, did the same, establishing some guiding principles for methodical observation. One of his major revelations was that the Arctic Ocean is extremely deep.

For any researchers working on the Lance, there's a rotation off the ship every six weeks by helicopter. By contrast, for the men on the Fram, there was no escape for three long years from 1893-6.

The clothing has improved immeasurably. Everyone venturing onto the ice now has to wear a floatation suit and during our worst weather, when the wind chill was minus 47C, it was just about possible to work outside. Nansen and his men, in a mix of wolf-skin and wool, must have felt the cold terribly and, if they slipped into the icy water, they just got soaked.

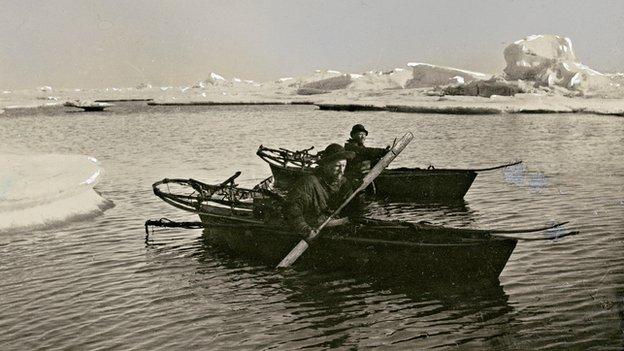

The Fram withstood forces that no other vessel had managed before

And there's also been a huge cultural shift in how the polar wildlife is regarded.

These days, the scientists go to great lengths to avoid harming any creature that comes their way. So polar bears, which can be a dangerous threat, are scared away with snowmobiles or flare guns; rifles are a last resort.

Instead, in Nansen's time, the animals of the Arctic were seen as a source of food, as a means of survival. Seals, walruses and even polar bears were not just fair game but essential stock for the larder.

It may be shocking to read this now but Nansen was quite open in his account of the voyage: "We have eaten bear-meat morning, noon, and night, and so far from being tired of it, have made the discovery that the breast of the cubs is quite a delicacy."

At the end of his journey, Nansen wrote that he had "gone far to lift the veil of mystery" over the Arctic.

He also suggested that future expeditions should repeat his technique of using ships because the explorers would be more comfortable and could also bring their laboratories with them.

That is exactly what the Norwegian Polar Institute has done with the Lance, as if following his script.

But one can only guess at what Nansen would make of the helicopters and computers and other new technology, and of how the Arctic itself is being transformed.