Why do we sleep?

- Published

New research is giving scientists an insight into why we sleep and what happens when we do it

Sleep is a normal, indeed essential part of our lives. But if you think about it, it is such an odd thing to do.

At the end of each day we become unconscious and paralysed. Sleep made our ancestors vulnerable to attack from wild animals. So the potential risks of this process, which is universal among mammals and many other groups, must offer some sort of evolutionary advantage.

Research in this area was slow to take off. But recently there has been a series of intriguing results that are giving researchers a new insight into why we sleep and what happens when we do it.

Why do I sleep?

Scientists simply don't know for sure. In broad terms researchers believe it is to enable our bodies and especially our brains to recover. Recently researchers have been able to find out some of the detailed processes involved.

During the day brain cells build connections with other parts of the brain as a result of new experiences. During sleep it seems that important connections are strengthened and unimportant ones are pruned. Experiments with sleep-deprived rats have shown that this process of strengthening and pruning happens mostly while they sleep.

And sleep is also an opportunity for the brain to be cleared of waste.

A group led by Prof Maiken Nedergaard at the University of Rochester Medical Centre in New York discovered a network of microscopic fluid-filled channels in rats that clears waste chemicals from the brain. Prof Nedergaard told BBC News when her research was first published in 2013 that this process occurs mostly when the brain is shut off.

"You can think of it like having a house party. You can either entertain the guests or clean up the house, but you can't really do both at the same time."

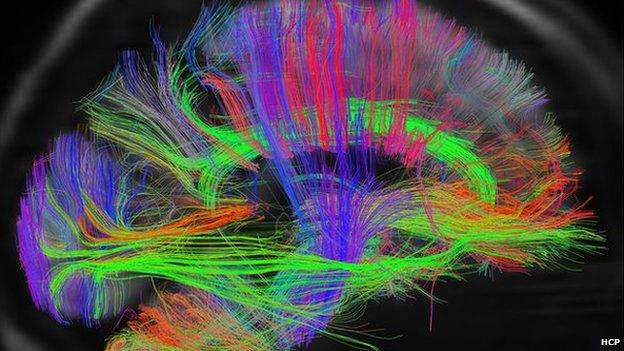

Sleep enables the brain's intricate wiring system to form and to clear out waste products

What happens when I don't get enough sleep?

It seems that a lack of sleep alters the way in which the genes in the body's cells behave.

Researchers at Surrey University in Guildford have found that genes involved in inflammation seem to increase their activity. Dr Malcolm von Schantz, who is involved with the Surrey research, believes that the genes are responding to lack of sleep as if the body is under stress.

He speculates that in the distant past in times of stress our ancestors' bodies would prepare themselves for injury by activating these inflammation genes which would cushion the effects of attacks by wild animals or human enemies.

"It puts the body on alert for a wound but no wound happens," he told BBC News.

"This could easily help explain the links between sleep deprivation and negative health outcomes such as heart disease and stroke."

In modern times though preparing for an injury that never happens has no beneficial effect - in fact the consequent activation of the immune system might increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Why is it hard to think when I am tired?

The expression "half asleep" might be an accurate description of what is going on in the brain when you are feeling slow-witted.

Research suggests that parts of the human brain may well be asleep when it is sleep-deprived. Studies on whales and dolphins show that when asleep they continue to use half of their brain to swim and come up to the surface for air.

A study on human patients, external showed that something similar goes on in our brains. As they became more sleep-deprived, parts of their brain became inactive while they were still awake.

What's more the local sleep areas move around the brain. So although when we go to bed we think one moment we are awake and then there is an abrupt change to sleep - it may well be more of a continuous process.

What is the role of dreaming?

What is the purpose of dreaming? A new dream-reading machine could help scientists find out

That's a question that psychiatrists, notably Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud, have tried to answer but with limited success. More recently a team at the ATR Computational Neuroscience Laboratories in Kyoto in Japan has begun trying to answer some of these questions by building the beginnings of a dream-reading machine, external.

They asked volunteers to doze off in an MRI scanner and recorded their brain patterns. The volunteers were then woken up and asked to tell researchers what they were dreaming about.

The team then listed 20 separate categories of dream content from these accounts such as dwelling, street, male, female, building or computer screen. The researchers then compared the accounts with the pattern of activity in the area of the brain responsible for processing visual information - and to their amazement they found that there was a correlation. So much so that they could predict which of the 20 different categories they had listed the patient had dreamt of with 80% accuracy.

The device is a very rough tool but it may well be a first step to something that can see in more detail what happens in our dreams and so help researchers learn more about why we dream.

How is modern life affecting our sleep patterns?

Several studies show that the light bulb has led people shifting their day and getting less sleep. On average we go to bed and wake up two hours later than a generation ago.

The US Centres for Disease Control reported in 2008 that around a third of working adults in the US get less than six hours sleep a night, which is 10 times more than it was 50 years ago. In a later study it was also reported that nearly half of all the country's shift workers were getting less than six hours sleep.

And a study led by Prof Charles Czeisler of Harvard Medical School found that those who read electronic books before they went to bed took longer to get to sleep, had reduced levels of melatonin (the hormone that regulates the body's internal body clock) and were less alert in the morning.

The light bulb and the pressures of modern life have shifted our sleep patterns but at what cost?

At the time of publication he said: "In the past 50 years, there has been a decline in average sleep duration and quality.

"Since more people are choosing electronic devices for reading, communication and entertainment, particularly children and adolescents who already experience significant sleep loss, epidemiological research evaluating the long-term consequences of these devices on health and safety is urgently needed."

What's stopping you sleeping?

One in eight of us keep our mobile phones switched on in our bedroom at night, increasing the risk our sleep will be disturbed.

Foods such as bacon, cheese, nuts and red wine, can also keep us awake at night.

Many studies report that there is evidence that sleep loss is associated with obesity, diabetes, depression and lower life expectancy - while others, such as Prof James Horne, a sleep researcher at Loughborough University believes that such talk amounts to "scaremongering".

"Despite being 'statistically significant', the actual changes are probably too small to be of real clinical interest," he told BBC News. "Most healthy adults sleep fewer than that notional 'eight hours' and the same went for our grandparents.

"Our average sleep has fallen by less than 10 minutes over the last 50 years. Any obesity and its health consequences attributable to short sleep are only seen in those few people sleeping around five hours, where weight gain is small - around 1.5kg per year - which is more easily rectified by a better diet and 15 minutes of daily brisk walking, rather than by an hour or so of extra daily sleep."

A team from the universities of Surrey and Sao Paulo in Brazil have spent the past 10 years tracking the health of the inhabitants of Bapendi, a small town in Brazil where modern day lifestyles haven't yet taken hold.

Many of the inhabitants of this town get up and go to bed early. The investigators hope to find out soon whether the old adage "early to bed and early to rise" really does make us, if not "wealthy and wise", at least "healthy and wise".

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published24 March 2015

- Published15 March 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published12 May 2014