Unsettled Earth continues to rattle Nepal

- Published

Some buildings weakened over the past fortnight were toppled

By any stretch, a magnitude-7.3 quake is a big one.

Tuesday's shaker in Nepal is not quite as bad as the 7.8 tremor on 25 April - which was 5.5-times as energetic - but it is a major quake nonetheless.

The location is different. The epicentre this time is about 80km east-northeast of Kathmandu, halfway to Everest. A fortnight ago, the event began 80km to the northwest of the capital.

But just that observation is instructive because of what we have learnt in the past two weeks.

In April, we saw the fault system rupture eastwards from the epicentre for 150km. And the immediate analysis suggests Tuesday's tremor has occurred right at the eastern edge of this failure.

In that context, this second earthquake was almost certainly triggered by the stress changes caused by the first one.

Indeed, the US Geological Survey had a forecast for an aftershock in this general area.

Its modelling suggested there was 1-in-200 chance of a M7-7.8 event occurring this week. So, not highly probable, but certainly possible.

Quake experts often talk about "seismic gaps", which refer to segments of faults that are to some extent overdue a quake.

Tuesday's big tremor may well have filled a hole between what we saw on 25 April and some historic events - such as those in 1934, which occurred further still to the east.

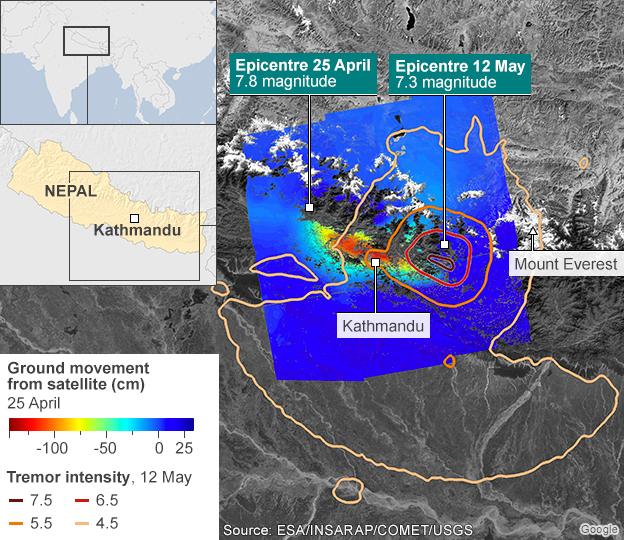

A comparison of 25 April and 12 May

The graphic shows satellite measurements of the ground movement in April's big quake, overlaid with an early model of expected shaking from Tuesday's tremor.

Satellites can measure the relative movement of the ground towards and away from them, in "before" and "after" images of a quake zone. Reds therefore indicate areas of uplift, while blues denote land that has subsided. The 12 May epicentre, together with its expected radiating pattern of shaking, is centred right at the eastern end of the 25 April rupture.

There are early reports of deaths and injuries, and one has to hope the outcome this time will be less severe.

Buildings that were left damaged and precarious on 25 April may well have been felled in the following days' aftershocks, or have been put out of bounds. This could limit the casualties this time. But further landslides and avalanches in the mountainous terrain are a persistent risk. And, of course, another big tremor does nothing for the frayed nerves of an already anxious population.

For the future, it is clear there are still large segments of the fault that retain strain, and these regions are where resilience planning is likely to be concentrated.

Satellite images show the 25 April quake did not rupture all the way to the surface, meaning there is potential for another big quake just to the south of Kathmandu. And there are particular concerns to the west, as well.

"I think if you spoke to most people, they would say the biggest patches that didn't break a fortnight ago were the shallower patches, south of Kathmandu; and also west of Kathmandu, or at least west of where it started on 25 April at Pokhara," explained Dr John Elliott from the Nerc Centre for the Observation and Modelling of Earthquakes and Tectonics (Comet), external at Oxford University, UK.

"So, there is that whole portion of western Nepal that hasn't gone since the 1500s. This aftershock was quite big at 7.3 but we'd have concerns still about 8.0s to the west of Pokhara," he told BBC News.

Shake assessments

The death toll from the 25 April earthquake now stands at more than 8,000. This is a dreadfully high number, but it is worth remembering the estimates that were produced by the predictive models on that day. These suggested the number of dead could be in the tens of thousands.

It is very probable that the final toll will be higher than what has so far been recorded, but there are indications that the numbers might not be quite so high. An interesting story is emerging about the shaking on 25 April. It seems the fault may have ruptured in a smoother fashion than might have been anticipated, resulting in less destruction.

Dr Susan Hough from the US Geological Survey has been reviewing the data.

She told the BBC: "We can see directly that central Nepal moved up about 1.5m during the earthquake and also to the south, but it did so very gradually, if you will.

"You can see that in videos that show the ground just moving back and forth with a very long period, on the order of five seconds.

"So, you would have had buildings in Kathmandu that were able to ride out what would have been essentially long swells of the ground moving beneath them."

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external