Bloodhound supersonic car gets tough underbelly

- Published

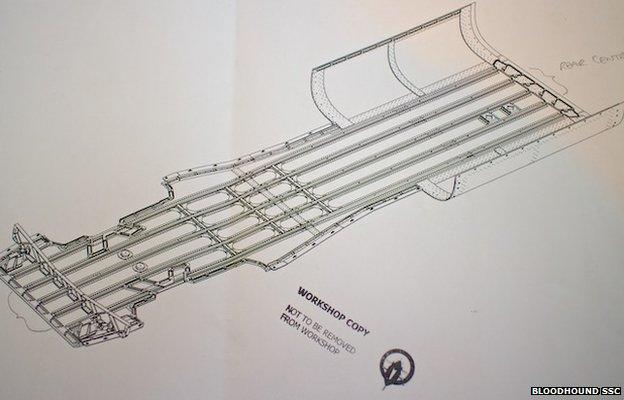

The floor will be one of the hardest working engineering elements on the vehicle

When Andy Green "floors it" in the South African desert later this year, he expects to be able to break his 18-year-old land speed record.

His British Bloodhound Super-Sonic Car (SSC) is aiming for 800mph (1,290km/h).

To achieve this extraordinary speed, the RAF man will depend on many cutting edge technologies and components - not least the actual "floor" itself.

This piece of titanium panelling will be one of the hardest working engineering elements on the vehicle.

It has to protect the underside of the car from the blizzard of dust and grit that will be produced as Bloodhound streaks across the dry lake surface of Northern Cape's Hakskeen Pan.

One of the strongest primary shockwaves will form right between the supersonic vehicle's front wheels.

This will turn and churn the dried mud, and, with the help of the spinning wheels, shotblast Bloodhound's body.

When Andy Green set the existing record of 763mph (1,230km/h) in 1997, his Thrust machine was badly eroded by the playa it kicked up in its path. Thrust's aluminium floor was polished to a high-sheen finish and rubbed wafer thin in places.

The protective belly of the record-breaking Thrust vehicle was badly eroded in 1997

The new titanium floor just finished at Bloodhound's technical centre in Bristol hopes to perform much better in even more demanding circumstances.

"At Swansea University, we set up a test rig where we took the same material from Hakskeen and fired it at different panels to find the material that would cope in this high-speed eroding environment - and that was titanium," explained Conor La Grue, the components chief on the Bloodhound project.

The new floor was assembled by a team from 71 Squadron, whose normal day job is to keep the jets of the Royal Air Force in a state fit to fly.

The floor structure runs from the rear chassis to the front wheels

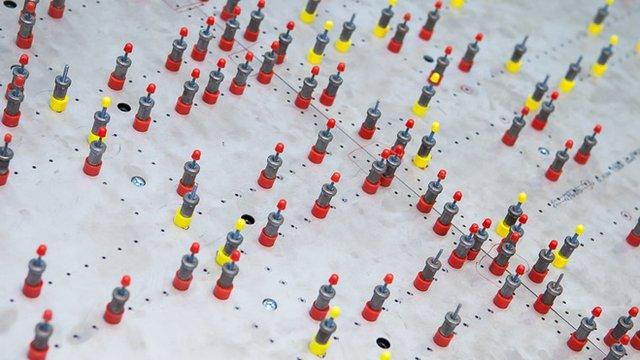

There are more than 4,500 rivets - careful work that will be hidden under the car

The structure contains about 240 primary parts and has required roughly 1,000 worker hours to put together.

As well as two broad titanium skins, the floor structure incorporates a multitude of other sections, including ribs, stiffeners, stringers, edge members, straps, buttstraps, doublers, brackets and cover plates.

And the whole structure is held together by 54 anchor nuts, bolts, washers and bushes, and 4,547 aerospace grade rivets. These rivets require immense patience to emplace.

Each rivet hole involves pilot drilling, de-burring, pinning, drilling out to full diameter, de-burring again, pinning again, counter sinking and de-burring a final time.

"71 Squadron have been incredible. Their skill of hand is quite extreme, and they're amazing to watch," observed La Grue.

And yet, all of this exquisite work will essentially be seen by no-one because it will be hidden under the car. But work, it must.

Bloodhound SSC is moving towards completion at its technical centre in Bristol

It is quite possible that the shockwave created between the front wheels will travel ahead of the car, pulverising the desert surface layer fractions of a second before Bloodhound arrives, creating even more mess for the floor to deal with.

"There's an interesting premise here that the shock energy will travel faster through a solid than through air," said La Grue.

"So, potentially, the ground ahead of the car could already be coming apart before the car gets to it. We won't know that for sure until we start running, but it would only make the scenario worse because you'd already have loose material available even before the wheels and the shockwave pick it up and throw it all over the place."

The assembly of Bloodhound is now reaching a critical phase.

British aerospace companies involved in the project are sending their components to Bristol for final integration.

The plan is to roll Bloodhound out the door in late summer for a slow-speed test on the runway of the Newquay Aerohub in Cornwall.

Assuming that goes well, the vehicle will then be shipped to South Africa to begin its assault on the land speed record.

The intention is to smash that this year before returning to Hakskeen Pan in 2016 to raise the mark beyond 1,000mph (1,610km/h).

The aim this year is to break the existing record, and then go beyond 1,000mph in 2016

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published7 May 2015

- Published28 April 2015

- Published25 March 2015

- Published14 March 2015

- Published2 March 2015