Advanced Ligo gravitational wave hunt is green lit

- Published

The upgrade includes significant contributions from Australia, Germany and the UK

One of the great physics experiments of our age looks ready to begin its quest.

Scientists have held a dedication ceremony to inaugurate the Advanced Ligo, external facilities in the US.

This pair of widely separated laboratories will be hunting for gravitational waves.

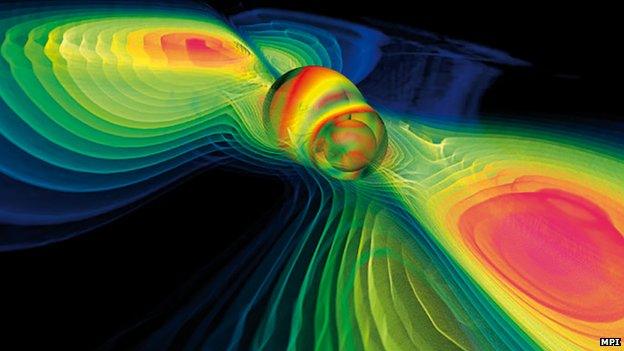

These ripples in the fabric of space-time are predicted to result from extreme cosmic events, such as the merger of black holes and the explosive demise of giant stars.

Confirmation of the waves' existence should open up a new paradigm in astronomy.

It is one that would no longer depend on traditional light telescopes to observe and understand phenomena on the sky.

"Advanced Ligo represents a critically important step forward in our continuing effort to understand the extraordinary mysteries of our Universe," said France Córdova, the director of the US National Science Foundation.

"It gives scientists a highly sophisticated instrument for detecting gravitational waves, which we believe carry with them information about their dynamic origins and about the nature of gravity that cannot be obtained by conventional astronomical tools."

Although based in the American states of Washington and Louisiana, and led by the MIT and Caltech institutions, Advanced Ligo is very much an international project.

It has drawn on the expertise of 15 other nations, with particularly significant contributions coming from Germany, the UK and Australia.

Tuesday's dedication ceremony at the Hanford lab in the US northwest paves the way for the experiment to begin its search in earnest towards the end of the year.

The laser light is bounced down long vacuum tunnels

Researchers have spent the past eight years, and more than $200m, upgrading equipment at both facilities to a new level of sensitivity.

Ligo stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatories. Both Hanford and its sister lab in Livingston in the US southeast work on the same principle.

The idea is to split a high-powered laser beam and send separate light paths down two long vacuum tunnels arranged in an L-shaped configuration.

The two paths are then bounced back by mirrors to their starting point, where the beam is reconstructed at detectors.

If gravitational waves have passed through the lab, the light should show evidence at the detectors of having been ever so slightly disturbed.

But the expected weakness of gravitational waves means only astrophysical phenomena on a truly massive scale, such as coalescing compact (neutron) stars, are likely to generate detectable signals.

And even then, the technology has had to be pushed to the limits to get into the sensitivity ranges demanded.

Ripples in the fabric of space-time

GWs are an inevitable consequence of the Theory of General Relativity

Their existence has been inferred by science but not yet directly detected

They are ripples in the fabric of space and time produced by violent events

Accelerating masses will produce waves that propagate at the speed of light

Detectable sources ought to include merging black holes and neutron stars

Ligo fires lasers into long, L-shaped tunnels; weak GWs should disturb the light

When Ligo was first established, it was capable of measuring disturbances in the set-up equivalent to one one-thousandth of the width of a proton, one of the particles that make up all atoms.

The improvements installed in the last few years should make Advanced Ligo 10 times more sensitive.

"We have a standard measure to track the improving performance of the detectors as they are commissioned, and in round numbers both detectors are now operating with a range close to 200 million light-years. So, a truly phenomenal distance, and within that volume there are very many galaxies, and if an event takes place in one of those galaxies when the detectors are online - which they will be increasingly towards the end of the year - it should be seen," explained Ken Strain, deputy director of the Institute for Gravitational Research, external at the University of Glasgow and principal investigator of the Advanced Ligo project team in the UK.

Further refinements would increase the sensitivity by a factor of three by 2020, Prof Strain told BBC News.

But as good as the new Ligo equipment is, no detection will be possible without an immense computing capability to sift the data. The gravitational signals will be buried in a sea of noise. Even the natural motions of the atoms that make up the ultra-pure fused-silica mirrors will have to be subtracted to discern the delicate distortion imprinted on the laser light by a passing wave.

The models suggest this should be happening perhaps a few times a year at first.

"Every time we open a new window on the Universe, we make surprising discoveries," said Prof Strain. "That was true for example with radio astronomy, which led quickly to the discovery of pulsars. And we expect the same with gravitational wave astronomy.

"Gravitational waves are produced by the bulk moving mass of an object. In the case of a supernova, this is the very core of the exploding star. And while today we can view a supernova optically with telescopes - we see the flash - we don't really know how it is produced. But if we can detect the gravitational waves from that supernova, we'll gain information directly about the underlying mechanisms."

Although based in the US, the project is very much an international collaboration

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published28 February 2015

- Published28 November 2013