Hubble studies Pluto's wobbly moons

- Published

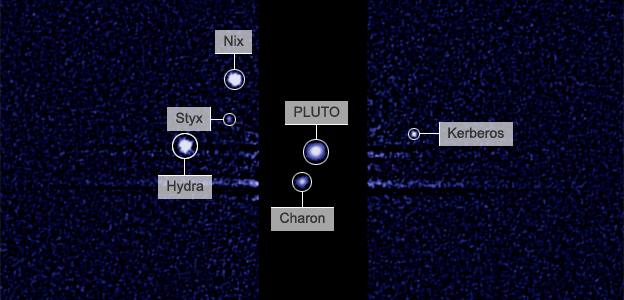

The Pluto system has five known moons. Others may be discovered in the coming weeks

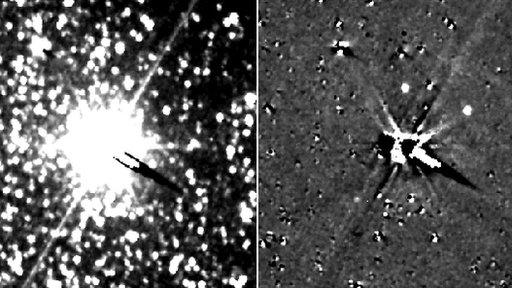

Hubble has revealed fascinating new details about Pluto's four smaller moons.

At a distance of five billion km, the telescope only sees the satellites as faint pinpricks of light, and yet it has been able to discern information on their size, colour, and rotational and orbital characteristics.

Hubble finds the little objects to be somewhat chaotic in their behaviour.

They are very likely wobbling end over end as they move through their orbits.

"If you can imagine what it would be like to live on [these moons], you would literally not know where the Sun was coming up tomorrow," said Mark Showalter from the Seti Institute, US.

"The Sun might rise in the west and set in the east. The Sun might rise in the west and set in the north for that matter.

"In fact, if you had real estate on the north pole… you might discover one day you’re on the south pole."

'Rugby ball'

The assessment, published in Nature journal, external, will be verified in six weeks when the moons are passed by a probe.

Nasa's New Horizons spacecraft is currently bearing down on the Pluto system and will execute a fly-through on 14 July.

It will gather a mass of data on the dwarf planet and its largest moon, Charon, but should also get a decent view of the smaller bodies - Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra – as well.

All were discovered by Hubble after New Horizons launched from Earth in 2006.

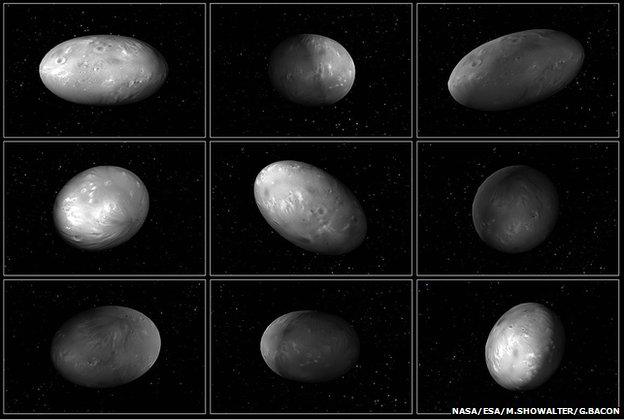

Nix and Hydra are the bigger of the quartet at about 50km in their longest dimension. And that is actually one of the keys to the observed behaviour.

These small satellites are very irregular in shape – more rugby ball than football.

Like clockwork

The Hubble scientists find that when you put this kind of object in the “lumpy” gravity field created by the dominant Pluto and Charon, you can get that object to tumble in unpredictable ways.

This wobbling is evident to the space telescope from the way the light from Nix and Hydra changes over time. And although it is harder to see the much smaller Styx and Kerberos, it is assumed their behaviour is the same.

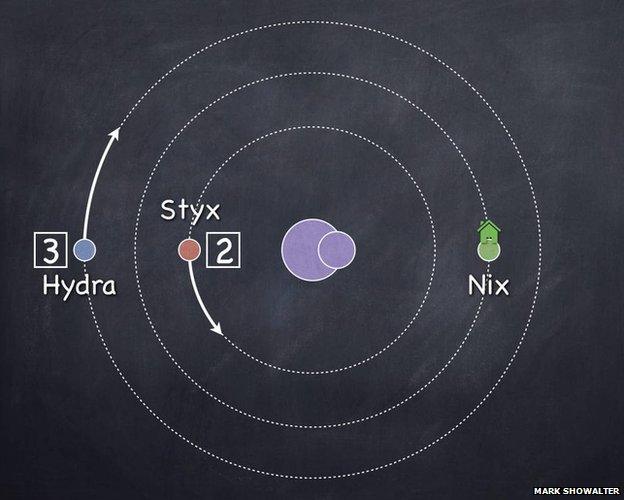

All that said, the moons do seem to follow a surprisingly predictable pattern as they orbit Pluto and Charon.

Three of them - Nix, Styx and Hydra - are locked together in resonance, meaning that their orbits follow a clockwork-like routine.

If you were to stand on Nix, Styx would come around on the sky twice in the time it took Hydra to come around three times.

A computer model shows how the "rugby ball" Nix tumbles unpredictably

Stand on Nix, Styx would come around twice in the time Hydra came around three times

Nix and Hydra are determined to be quite bright, akin to dirty snowballs. The surprise is Kerberos which orbits between them. It is really dark, not dissimilar to a charcoal briquette.

This is strange. Theory holds that all the moons, including Charon, were formed from the debris that resulted when the early Pluto was struck by an object of near comparable size.

"And if they all formed together, they all formed out of the same stuff. It is extremely hard to understand how one of them is a charcoal briquette and it’s orbiting between two snowballs," commented study co-author Douglas Hamilton, from the University of Maryland.

Some answers should come with New Horizons.

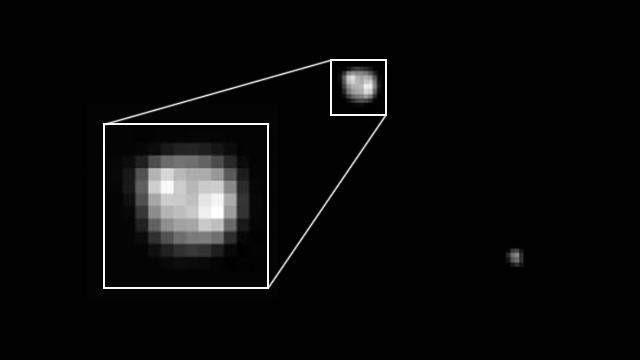

John Spencer, a mission scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, explained: "We’ll be taking pictures of Nix and Hydra that will be 50 to 100 pixels [across] - maybe bigger depending how bright they turn out to be.

"So, we’ll see a lot of their surfaces. We’ll see if they have craters or fractures, or anything like that and we’ll get the composition of their surfaces." Styx and Kerberos, because of their longest dimensions are probably about 10km, will be harder to characterise.

Nonetheless, whatever New Horizons learns at Pluto will be useful for those scientists that study even more distant realms, such as far-off double, or binary, stars, according to Heidi Hammel, of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

Where you have two suns very close to each other, you may get unusual behaviours in any nearby orbiting planets.

The Pluto-Charon system could therefore be analogous, she said, and the techniques used by Hubble in this investigation could soon be applied to the study of these more distant systems.

"A planet that circles a binary star is called a circumbinary planet," she explained, "and perhaps the most famous circumbinary planet is not actually a real planet but rather a movie planet – Tatooine in Star Wars, external, the planet where the young Luke Skywalker encountered Obi Wan Kenobi and began his journey to become a Jedi Knight.

"That’s a fictional circumbinary planet; we now know of at least 17 circumbinary planets, and several of those are in circumbinary systems – in other words, more than one planet revolving around the binary star."

Artist's view of Pluto: All will become clearer when New Horizons passes through on 14 July

A New Horizons image of Pluto taken from a distance of 75 million km in mid-May

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published13 May 2015

- Published30 April 2015

- Published15 April 2015

- Published5 February 2015

- Published25 January 2015