Madagascar's lemurs cling to survival

- Published

- comments

David Shukman goes in search of lemurs in their natural habitat

The famous lemurs of Madagascar face such severe threats to their survival that none of them may be left in the wild within 25 years.

That stark warning comes from one of the world's leading specialists in the iconic animals.

Deforestation and hunting are taking an increasing toll, according to Professor Jonah Ratsimbazafy, director of GERP, a centre for primate research in Madagascar.

"My heart is broken," he told the BBC, "because the situation is getting worse as more forests disappear every year. That means the lemurs are in more and more trouble."

So far 106 species of lemur have been identified and nearly all of them are judged to be at risk of extinction, many of them critically endangered.

The habitats they depend on - mostly a variety of different kinds of forest - only exist in Madagascar.

"Just as fish cannot survive without water, lemurs cannot survive without forest, but less than 10% of the original Madagascar forest is left," said Prof Ratsimbazafy, who is also a co-vice chair of the Madagascar primates section of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

"I would believe that within the next 25 years, if the speed of the deforestation is still the same, there would be no forest left, and that means no lemurs left in this island."

Deforestation and hunting in Madagascar are taking a devastating toll on lemurs

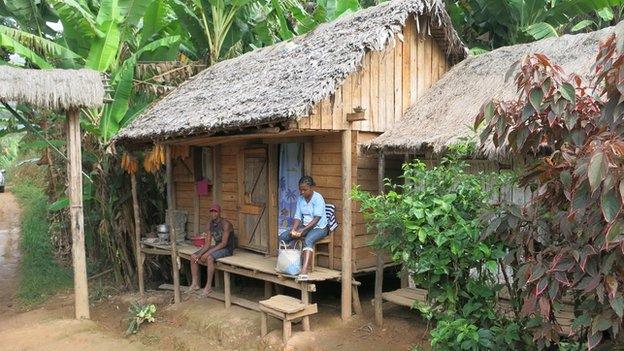

The pressure to clear the forests comes from a rapidly growing but extremely poor population seeking to open up new farmland. At least 92% of people in Madagascar live on less than the equivalent of $2 a day.

A form of slash-and-burn agriculture known as "tavi" sees trees felled and undergrowth scorched to make way for fields of rice and other crops.

Video of one recent forest clearance shows an apocalyptic scene of an entire hillside of charred stumps and smouldering vegetation.

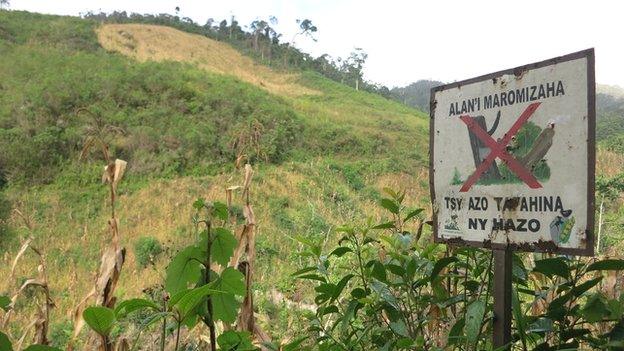

In one supposedly protected area I visited in eastern Madagascar, a sign announcing a prohibition on tree felling stood ignored amid new plantations of banana palms and maize.

Conservationists have long argued that slash-and-burn farming is needlessly damaging, leaving the soil unproductive after a few years, and that more intensive forms of cultivation would allow more forests to be left standing.

The government of Madagascar has recently confirmed that as much as 10% of the country is now earmarked in some way for wildlife - from national parks to what are called protected areas - but the rules are often not enforced at a local level.

A form of slash-and-burn agriculture known as 'tavi' sees trees felled and undergrowth scorched

Prof Ratsimbazafy said: "We have a struggle. Sometimes there is engagement on paper but sometimes it's not in reality because on the ground there is still deforestation."

He recalled how a new species of mouse lemur had once been discovered and identified in a forest only for that land to be "turned into a field of cassava" two years later.

The only long-term solution, according to Prof Ratsimbazafy, is to engage communities and persuade them that the forests - and the lemurs - have a value that is worth safeguarding.

In one protected area, Maromizaha, his organisation, GERP, is hiring local people to keep watch over the forest and to act as guides for tourists, making the point that the lemurs can worth more alive than dead.

It is also supporting new ventures in the local village including fish-farming and bee-keeping, and teaching new techniques for rice-growing that do not require constant expansion into the forest.

Nearby, a reserve known as Mitsinjo is run by a cooperative group set up by guides who encourage eco-tourism and ensure that the lemurs are safe - a model of management widely seen as promising.

Persistent poverty remains an obstacle to tackling the threat to lemurs

But there is an additional threat to the lemurs that stems from persistent poverty and widespread hunger - a continuing demand for bushmeat.

Although it is illegal to kill lemurs, poachers are still setting traps for the animals or shooting them, either for their own consumption or to be sold to others.

There are no reliable estimates for the scale of the losses but in one vulnerable area it is thought that as many as 10% of the population of lemurs could be killed ever year.

A local NGO called Madagasikara Voakajy recently investigated the bushmeat trade and photographed lemurs being hunted, butchered and eaten.

The organisation's director, Julie Razafimanahaka, told us that her researchers persuaded a hunter to allow them to observe him searching for the largest of Madagascar's lemurs, the Indri, famous for their size and black, white and grey fur.

"My team met with the hunter and followed him in the forest and saw him using guns and shooting the Indris and bringing back five to the shops and small restaurants.

"Families were then cooking and eating them. That was very shocking."

Taboos broken

Although in the past it has been taboo or what is called "fady" for local communities to eat lemurs, the increasing mobility of the population has brought in outsiders who do not care about old traditions.

In one gold-mining area, new arrivals persuaded local people to hunt Indri for them. And when the locals saw that breaking the taboo did not bring them bad luck, they too started eating the lemurs.

What had begun as a research project by Madagasikara Voakajy was quickly switched into a campaign to try to save the lemurs with an education campaign in schools.

According to Julie Razafimanahaka, a survey of opinion among children conducted after the campaign found a clear difference in attitude towards the lemurs.

"We have seen that children that have been educated are more aware of the protection status of the lemurs and they have a more positive perception so they would be sad if the lemurs were dying and they would be happy to see one.

"Whereas children at schools where we didn't do the education still thought lemurs were bushmeat - they thought they could eat them and most didn't care if there were lemurs or not because they're just like any animals."

Meanwhile another study into lemurs came up with a finding that complicates the campaign to save the animals: children that were fed lemurs suffered less malnutrition than those that were not.

The most recent comprehensive survey of lemurs was published in 2013 by the IUCN, the Bristol Conservation and Science Group and Conservation International.

It concluded that 94% of lemur species were at risk - an increase from 66% only seven years earlier - and highlighted the urgent need to engage local people, foster eco-tourism and maintain a permanent research presence in the forests.

But the report also signalled that breeding colonies should be set up to ensure that the animals at least survive in captivity, if not in the wild, as a strategy of last resort.