Juvenile camels 'key source' of Mers

- Published

Mers is an emerging human infection, so scientists want to untangle the dynamics of the virus in camels

Camels aged less than four years might be a major source of Mers, according to new research.

An international team looked for evidence of current or past infection in more than 800 dromedary camels.

They found that more than 90% of animals became infected by the age of two and virus shedding was more common in calves than in adults.

The scientists argue that changes in animal husbandry may reduce the occurrence of human Mers infections.

The study is published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The first reports of human Mers coronavirus infection emerged in June 2012, although cases are likely to have occurred before then.

More than 1,100 cases have been recorded and more than 400 people have died. Infections have been seen in 25 countries across Europe, Asia and Africa, but Saudi Arabia has experienced the biggest burden.

Because of its devastating effects in humans scientists have been searching for the source of the virus, to try to identify ways in which human infections can be prevented.

Speaking to BBC's Science in Action, Dr Müller who was involved in the earlier ground-breaking research looking for the origins or Mers said, "We could identify, in South Africa, bats that were carrying ancestral viruses: viruses that are [evolutionary] older than the Mers virus that we are seeing today".

Out of Africa

But, whilst related, these bat viruses were distinct from the Mers virus cropping up in humans. There had to be another source.

Following a brainstorming meeting between the Bonn scientists and colleagues based at the Erasmus Medical College in the Netherlands, the researchers focussed their efforts on animals that had close contact with humans living in the Middle East: horses, cattle, sheep, goats and dromedary camels.

The finding from their initial work was clear. Dromedary camels living in the Middle East had antibodies that recognised Mers virus protein - a strong sign of past infection. None of the other animals tested contained these.

To gain further insight into the origins of this emerging human infection and the link to camels, the team then looked at samples obtained from dromedary camels living in other countries.

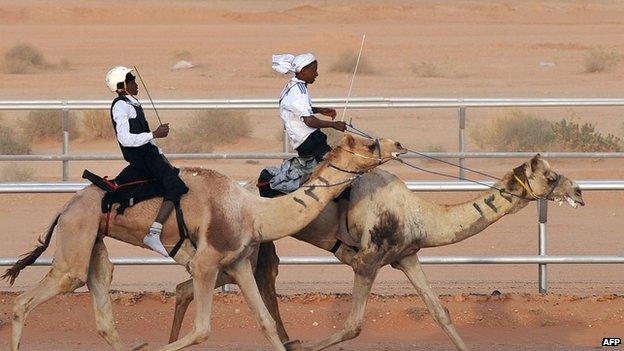

In Saudi Arabia, camels are bred for racing among other uses

The presence of Mers-reactive antibodies alone is not sufficient evidence - some antibodies can occasionally recognise several viruses belonging to the same families. So, rather than rely on the presence of antibodies alone, the team decided to look for the presence of neutralising antibodies - the antibodies that are able to stop a virus from infecting a cell - as these tend to be far more specific.

"What we could see is that dromedary camels, not only in the Arabian Peninsula but also in Africa where most of the camels are bred then exported to the Arabian Peninsula, have really high levels of neutralising antibodies, which means that they must have been infected with Mers, or a very similar virus," Dr Müller said.

"And we could see that, even in [samples obtained in] 1983, camels in Sudan and Somalia had neutralising antibodies."

Clearly, Mers infection of camels in Africa and the Middle East was rife and this data highlighted that camels had been infected for decades. The buoyant international camel trade running between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula would have provided ample opportunity for the virus to spread.

Blame the little ones

This past work provided a powerful argument that Mers virus was circulating in camels but it still wasn't clear whether particular groups of animals posed the biggest risks to humans. Knowing this might help in the development of measures aimed at reducing human infections.

In the current study published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, an international team drawn from Bonn, Hong Kong and Dubai, looked at more than 900 camels living in Dubai for signs of both past and current Mers infection, in order to answer this camel conundrum.

The camels were being farmed for their milk and meat and for racing.

Blood, nose swabs or saliva samples were tested for the presence of Mers antibodies or for the presence of virus itself.

The vast majority of samples from animals aged more than two years contained Mers antibodies, showing that the virus is a common camel juvenile infection.

Crucially, active virus infection was observed far more frequently in animals less than four years old, with approximately 30% of camels aged less than one, shedding lots of virus.

So, it's these very young animals that pose the greatest threat to humans.

How the virus spreads to humans is still unknown.

It might be through direct contact with body fluids from infected camels. Juvenile camels are very wary of humans and will normally avoid contact with them. However, when the juveniles are separated from their mothers - usually at or before the age of two - they are brought into contact with humans and this provides the perfect opportunity to pass on any virus that they are shedding.

Alternatively, infection might also occur through drinking unpasteurised milk; possibly contaminated by transfer of virus present in the saliva of an infected calf onto the mother's teat during suckling.

Commenting on the infection risk, Dr Müller said "When it comes to being infected, I think you really need close contact and in particular behaviour like kissing camels, drinking raw milk, touching the nostrils and then touching your eyes. That's the way to get infected.

"It's not airborne, that's for sure, and you need quite a dose."

The authors of the latest study argue that simple changes in animal husbandry, like delaying the age that calves are taken away from their mothers, is likely to reduce the chance of human infection.