Why insects are marvels of engineering

- Published

Video showing how insects' legs allow them to be incredible acrobats (Footage courtesy of Dr Gregory Sutton and Prof Malcolm Burrows)

Insects solve some pretty wacky biological problems, says Dr Gregory Sutton.

And he should know. For almost a decade, he has been using high-speed cameras to reveal the secrets of the most acrobatic of the world's invertebrates.

Along with his colleagues at the Universities of Bristol and Cambridge, he is working out how fleas, locusts and even praying mantises take to the air. He presented some of his latest work at the Society for Experimental Biology's annual meeting, external in Prague on Thursday.

One of the problems these super-jumpers have is that to use a jump as an evasive manoeuvre, they must accelerate in a very short space of time.

A flea, for example, releases the energy in its legs in one thousandth of a second. A more robust grasshopper manages the feat in 30 thousandths of a second.

"There's a problem in how much energy a muscle can produce," explains Dr Sutton, "and the way they solve it is the same way we solve it with a bow and arrow."

When you draw an arrow, all the energy comes from your muscles, but it's stored by the bow, which amplifies the speed at which that energy is released - propelling the arrow forward.

These insects - fleas, grasshoppers, locusts and the froghoppers you find in many UK gardens - have similar springs that they can "ratchet up"; a sort of internal bow to store energy.

"A froghopper's jump is prefaced by a five second ratcheting-up," says Dr Sutton.

"They will sometimes walk around on their front four legs to keep that charged energy.

"We've found examples of springs, made of layers of hard insect cuticle and of a fluorescent blue protein called 'resilin'. This layering of the two materials gives the springs similar properties as modern composite bows."

And just like composite bows, this stores much more energy for the length of the bow - across the stretched outer layer and compressed inner layer.

Zipped-up legs

The other problem is that both of those back legs, which power the jump, have to "go" at exactly the same time.

"If the legs go at different times the insect will just spin," explains Dr Sutton.

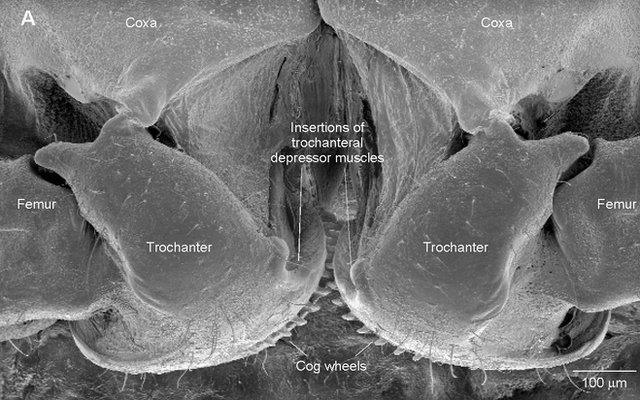

Micrographs show the "gears" locking together a planthopper's legs

While larger insects have friction pads to stick their legs together, some young planthoppers - a common British insect - are too small to have these pads.

"They have gears," says Dr Sutton - tiny cogs with interlocking teeth on the inside of each leg.

He and his colleague Dr Malcolm Burrows, from the University of Cambridge, have captured stunning microscopic images of these gears and and their interlocking teeth.

"The neatest hypothesis (about these) is that the nymphs are zipping their legs together for take-off," Dr Sutton says.

Ballet mantis

In another series of experiments that resulted in spectacular slow-motion footage, Dr Sutton and his colleagues looked at the surprisingly agile leaps of the long-limbed praying mantis.

When these insects jump, their bodies go into a spin. To control where they land, they have to control that spin.

The experiments revealed that the mantises were able to "adjust their their rotation appropriately" depending on where they need to land.

Like a ballet dancer, the praying mantis throws out its limbs to slow its spin as it moves through the air.

These leaping and landing strategies are important for the insects to survive in their environment, allowing a quick escape or a safe landing on the stalk of a plant while hunting.

As for Dr Sutton's next video - he is currently trying to film the individual hairs on the bodies of bees, which they use to sense and differentiate between flowers.

"I just see life as a series of stories," he adds.

- Published8 July 2013