Pluto flyby: Meet the 'King of the Kuiper Belt'

- Published

Jocelyn Bell Burnell spoke to BBC Newsnight about Pluto's status

Sometimes it is hard to comprehend the size of things in astronomy.

Just our Solar System, the little corner of the Milky Way in which we live, is vast.

Venetia Burney, the 11-year-old girl who in 1930 suggested the name "Pluto" for the newly discovered "planet", remembered playing games in Oxford's University Parks that would try to convey this scale.

She and her school chums would hang a two-foot-wide orb on the gates to represent the Sun, and then space out a caraway seed for Mercury and peas to signify Venus and the Earth.

Neptune was a lump of clay and sited a mile and a quarter from the gates.

"And then we were told the nearest star would be in China, and that really stuck with me," she recalled in a BBC interview.

Before she died in 2009, Venetia got to see the launch of Nasa's New Horizons probe to Pluto. It's even got an instrument on it that is named after her.

New Horizons was the fastest spacecraft ever despatched from Earth.

And on Tuesday, after nine-and-a-half years of travel at immense speed, it will finally reach the diminutive world, some 4.7 billion km away.

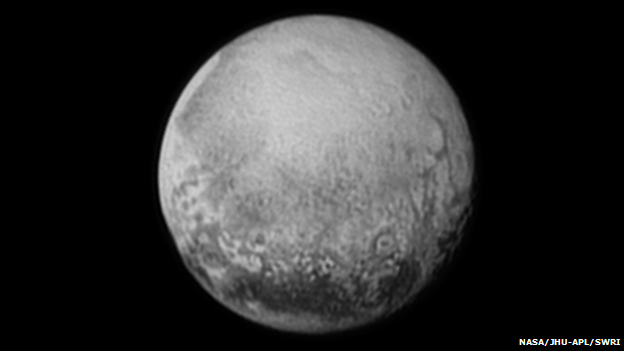

The 2,300km-wide Pluto, as seen on Saturday by the fast-approaching New Horizons

A few things have changed in the intervening years.

The first surely everyone now knows: Pluto is no longer regarded as a main planet and has been re-categorised as a "dwarf planet".

The second feeds into the first, and that is the recognition of just how numerous planetary bodies of all sizes are, not just within our Solar System, but around all the stars we see "beyond China".

Who'd have thought that some of these stars would have super-Earths and colossal Jupiters?

The arguments still rage over whether Pluto should be included in the planetary mnemonics that children learn in school.

But in many ways this is a distraction - and a distraction from something that is actually more interesting and really quite exciting.

Think about it for a moment: If the "classical nine" planets were all there were, then Tuesday would represent an ending. It would be the completion of a quest to map out our Solar System.

As it is, we now like to think of the reconnaissance of Pluto as just the start of something, as the beginning of the exploration of the "third zone".

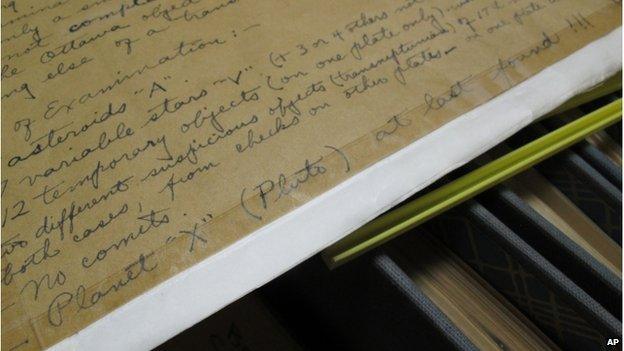

When US astronomer Clyde Tombaugh found Pluto, we had no idea that it had so many siblings

If the first and second zones encompass the rocky inner planets like Earth and the outer gas giants like Saturn, then this third sector covers all the smaller bodies like Pluto that orbit billions of km from the Sun. And they are legion.

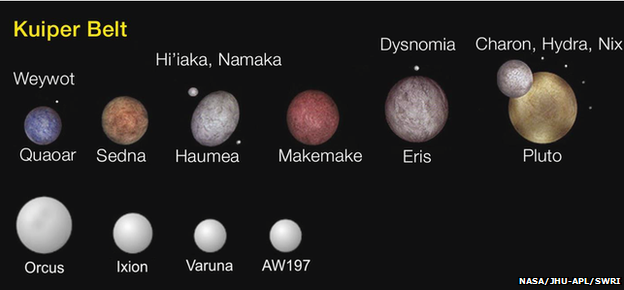

This third zone, known as the Kuiper Belt, probably contains hundreds of thousands of objects 100km and more across. Pluto, at about 2,300km wide, just happens to be the current "King of Kuiper Belt".

"Pluto is the biggest and brightest, and, as far as we know, it's the most interesting of this third class of planets," Alan Stern, the principal investigator on New Horizons, told BBC Newsnight.

"It was a wonderful discovery that our Solar System has this extra class and that - surprise, surprise - it is the most populous class. It's amazing: we had a completely upside-down view until the 1990s."

And not just in our Solar System. It is very probable that the dwarf planets are the most abundant type of planet in the Milky Way as a whole.

And remember, they will not all be dull balls of ice and rock.

"Right now we're just standing under the waterfall and enjoying it," Alan Stern told BBC Newsnight

As we're seeing on the approach to Pluto, many will have active processes shaping their surfaces. Some, just like Pluto, will even have atmospheres with evolving climates.

New Horizons should be thought of then as a sentinel.

It's the first mission designed to go and investigate this third domain.

After passing Pluto, it will be directed to a second Kuiper Belt object, which it will reach in another four years or so.

More missions will no doubt follow. Our problem currently is knowing where to direct them.

All manner of objects are now starting to turn up in the Kuiper Belt

Present telescopes struggle to see the third zone, to pick out the candidates most worthy of a spacecraft encounter.

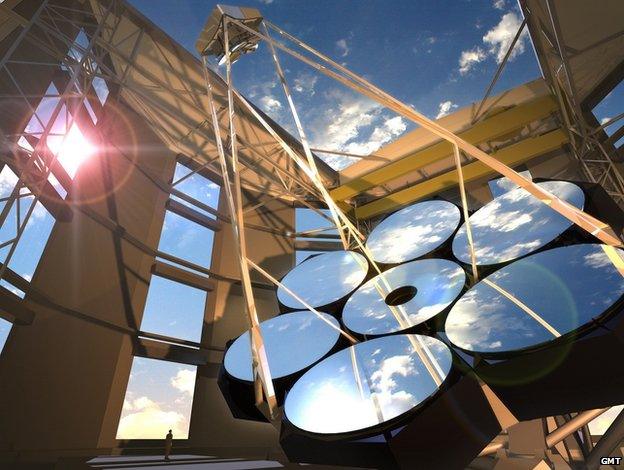

But this is all about to change. We're now building a new generation of monster observatories whose primary mirrors will be 30-40m across. These new telescopes will have the sensitivity and the resolution to open up the Kuiper Belt to a new era of study.

If you run the models, based on our best understanding, you would have expected a thousand or so Plutos to have been around in the early days of the Solar System, more than four billion years ago. But then we think there was a big re-organisation, and many of these objects would either have been destroyed in collisions, or scattered by close encounters with their own kind and the bigger planets.

Some will still be there, albeit perhaps further away than the Kuiper Belt, in an even more distant realm called the Oort Cloud.

The next generation of telescopes will have super-mirrors that will find many more objects

"If these models are correct, we should expect to find dramatically more small planets, and possibly some large planets that were also scattered out there - Earth-sized and Mars-sized," says Prof Stern.

Just a final aside on Pluto's demotion from "full" planet status.

I got the chance the other day to talk about New Horizons with the famous radio astronomer Jocelyn Bell Burnell. It was she who facilitated the technical meeting a few months after the probe's launch in 2006 that downgraded Pluto.

She could not be more excited about the next few days.

"I think New Horizons has come out of it very well," she told BBC Newsnight.

"By going to visit Pluto and one or two other objects in the Kuiper Belt, it is going to a zone that hasn't previously been explored. And I think it's brilliant.

"Being able to send spacecraft out that far is going to lead to a lot of new information and, hopefully, new understanding."

Jocelyn Bell Burnell facilitated the meeting of astronomers that demoted Pluto

You can watch a preview of the New Horizons flyby on Monday on BBC Two's Newsnight programme at 22:30 BST. The BBC will also be screening a special Sky At Night programme called Pluto Revealed on Monday 20 July, which will recap all the big moments from the New Horizons flyby.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published13 July 2015

- Published11 July 2015

- Published11 July 2015

- Published11 July 2015

- Published9 July 2015