New Horizons: Why bother exploring the Solar System?

- Published

- comments

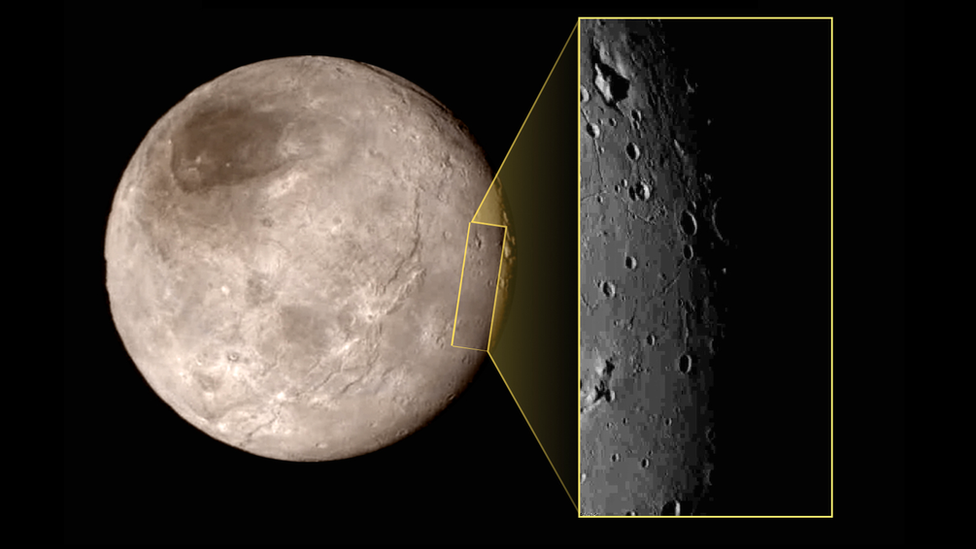

The mountain on Charon is surrounded by its "moat" is seen in the top-left of the rectangle

During a week of revelations about the strange worlds at the edge of the solar system, I repeatedly heard a question that often comes up about space: "why bother?"

It's a fair challenge. What is the point of spending taxpayers' money on a venture to Pluto or some other frigid corner of the cosmos?

Or having some of our greatest brains devoted to studying alien rock and ice when they could be working on problems much closer to home?

And nobody should duck the question. So here goes: should journalists like me, along with camera crews, even cover an event like the New Horizons mission?

This was first brought home to me during the European Space Agency's dramatic touchdown on a comet last November.

I thought the achievement was astounding and the excitement at the time was infectious. It even led to my first on-air hug.

But in the middle of it all, as my Twitter feed was in overdrive, I spotted a message from someone who was less than impressed. How would the knowledge gained from the venture, I was asked, benefit mankind?

Clear rationale

And something similar happened a few days ago at the very moment that the first signals confirmed that the Pluto flypast had worked.

One person demanded to know why the money spent on the spacecraft had not been used to help hungry people here on Earth. Another suggested that the mission left him as cold as Pluto itself.

So what is the justification for making an effort to explore space?

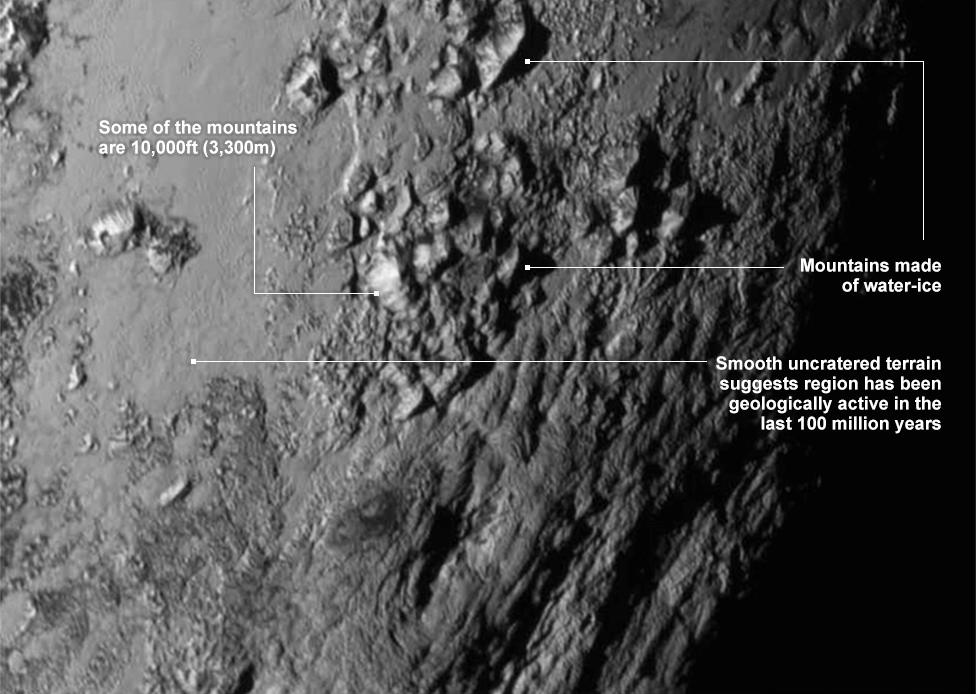

A new picture of Pluto's surface shows evidence of active geology and mountains comparable to the Rockies.

Back in the Cold War, there was the obvious motive for the United States and the old Soviet Union of demonstrating technological prowess.

But since then the push to investigate the Solar System has been much more about basic research.

From conversations with several of the mission scientists in the past few days, it's clear there's a burning desire to explain things that have remained mysterious until now.

Fundamental questions

Some of these are fundamental - like how the planets formed or how the moons were created or why the solar system has such a bizarre outer zone inhabited by Pluto.

Others' questions are more technical such as what processes are under way on Pluto's surface to keep smoothing over the craters left by meteorites or whether there's enough internal warmth to produce liquid water.

And for many people outside the field of planetary science, these issues might well be beguiling too - after all, they are essentially about the workings of our own neighbourhood in space.

The driver of the shuttle bus running between the Pluto press centre and the car park was among those fascinated by the mission - and the fact that after nine and half years of travel the New Horizons spacecraft arrived at its rendezvous 72 seconds early. To him, the feat was amazing in its own right.

But others still shrug their shoulders and ask what the fuss is about.

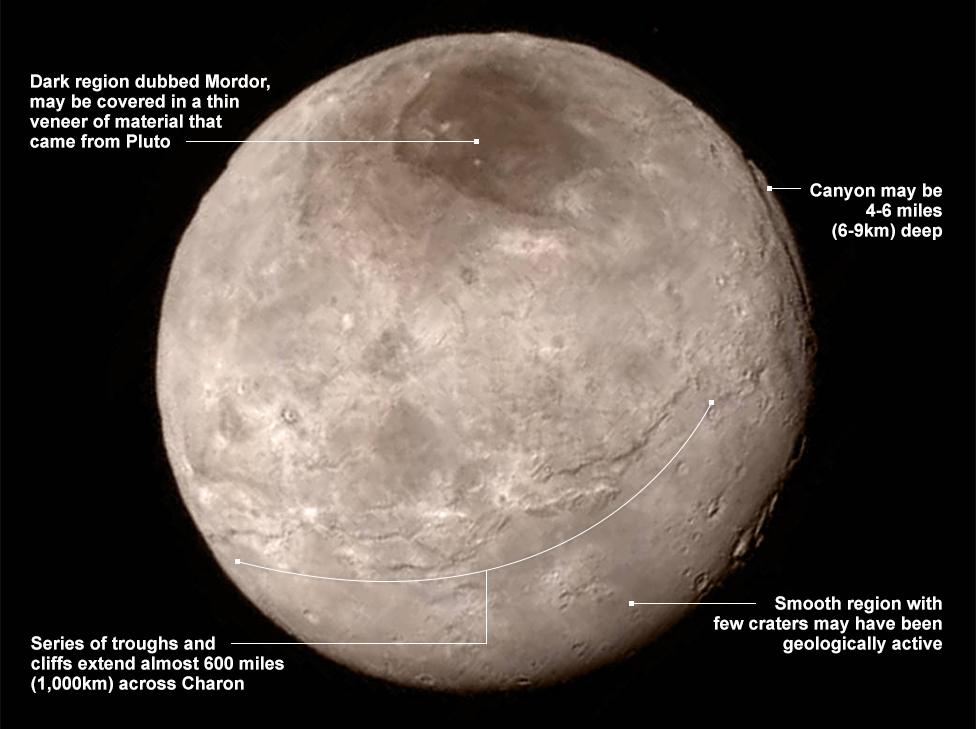

The probe also captured detailed images of Pluto's moon Charon during Tuesday's flyby

So when the "why bother?" question was put to me on air a few days ago, I found myself talking about our innate desire to explore.

I argued that our species has an instinctive curiosity. The same drive that urges us to climb to the brow of a hill in order to look over it also inspires a child to turn the next page.

And in the case of the chief scientist on the Pluto Mission, Alan Stern, it led him to repeatedly seek funding for his spacecraft when year after year he was rejected.

Persistence pays off?

So, I wondered, what would we have thought if Christopher Columbus or Captain Cook had spotted an unmapped coastline but turned away with a look of indifference and had not bothered to land?

To them, the lure of exotic new sights and undiscovered realms proved overwhelming. And nothing has changed.

The long trek to the edge of the Solar System paid off by producing staggering glimpses of alien worlds. When we all first saw the giant mountains of ice on Pluto and vast canyons on Charon, it took the breath away. And the images caught the imagination around the world.

The most powerful answer to the question "why bother?" may be the simplest: the thrill of witnessing discovery is its own reward.

Follow David on Twitter, external.