What makes a planet habitable?

- Published

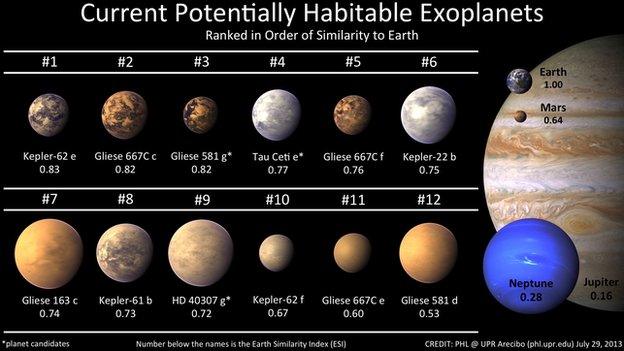

Scientists are looking for more rocky worlds that could possibly retain liquid water on their surface

Water in liquid form is thought to be a necessity for life on Earth.

Naturally, some say that life may flourish under other conditions, and perhaps even in the absence of water.

While that may be true, take a look around - life seems to do quite well here on Earth and we've yet to find it elsewhere in our Solar System.

Based on this, let's look at the classical definition for the habitable zone as the region around a star, such as our own Sun, where the temperature of any orbiting planet permits water in liquid form.

Astrophysicists are extremely good at calculating the temperature of a star and then, taking into account the distance of a planet from its host star, it is easy to work out the planet's "equilibrium temperature".

The starlight (in our case, sunlight) that falls onto the planet is reradiated as heat and, hey presto, we have our actual planet temperature - simple. Except it isn't.

Greenhouse gases

What if the planet sports a blanket of white clouds? Clouds are reflective and therefore will cool the planet, acting to push the habitable zone closer to the star.

Amusingly, if we calculate this "equilibrium temperature" for the Earth, taking into account its beautifully reflective clouds, then it turns out that we live outside the classical habitable zone!

The same calculation for Venus gives an expected equilibrium temperature of about -10°C, but in reality it is more like 450°C.

What happened?

Clouds' reflective qualities cool the planet and mean the habitable zone can be closer to a star

Both these planets have greenhouse gases present in their atmospheres, warming the planet up and driving the outer boundary of the habitable zone further away from the star (while clouds drive the inner boundary closer to the star).

The very latest habitable zone definitions use simulations of these cloud and greenhouse effects - widening and blurring the crude classical definition.

Throw into the mix that we currently can't study the atmospheres of rocky terrestrial exoplanets (and therefore have no idea whether they have clouds, greenhouse gases, or even an atmosphere at all!) - then to say "that planet is habitable" is impossible, for the time-being at least.

What is an exoplanet?

Planets beyond our Solar System are often given the term "exoplanet"

The first exoplanet was discovered in 1992, orbiting a pulsar (a neutron star that emits electromagnetic radiation)

A few years later, the planet 51 Pegasi B was found orbiting a star similar to the Sun

More than 1,000 have been detected to date using several techniques

Thousands more "candidates" await confirmation

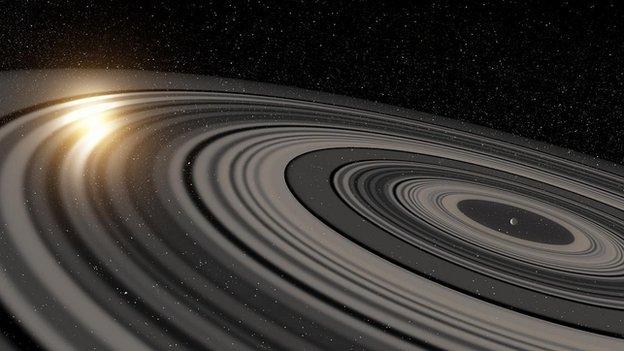

Many of these worlds are large planets believed to resemble Jupiter or Neptune

Many gas giants have been found to be orbiting very close to their stars

This has prompted new ideas to describe the formation and evolution of solar systems

Just to complicate matters, the habitable zone also depends on the type of star the planet orbits. The more massive and hotter the star, the further out the habitable zone will lie.

Conversely, small cool stars will have a habitable zone that is much closer in.

Indeed, "red dwarf" stars are so cool and dim that a planet in the habitable zone might have a "year" that lasts only a few days, so feeble is the red dwarf's light.

Stellar blasts

This would raise other problems for life on such a planet. Red dwarfs like to chuck out large flares, stellar eruptions that release charged particles and X-rays.

Given the close proximity of the planet, this might cause substantial atmospheric losses.

High doses of radiation also tend to be harmful to biological material, and X-rays are capable of dissociating water - thereby depleting any water supply. Not ideal.

Maybe things are better around hotter stars, where a habitable planet would lie further way from any nasty stellar blasts?

Well, now we run into another problem, that of the lifetime of the star.

Massive, hot stars are real gas-guzzlers. Yes, they may have far larger "fuel tanks" (they have a lot more mass to "burn"), but they gobble that fuel much, much faster, and die much younger than small, frugal cool stars.

For example, some of the most massive stars may live for only a few million years, while our Sun will hang around for about eight billion years.

Based on our knowledge of how life evolved on Earth, it is unlikely that even simple life would have time to evolve around stars that are all that much hotter than our Sun.

Returning to the diminutive red dwarf stars at the other end of the scale, these can hang around for about 100 billion years.

Perhaps if a planet DID hang on to its atmosphere, then over such a long time life might evolve to cope with being frequently doused in radiation?

Scorching hot

Well, we hit another issue - the fact that the variance in the amount of energy red dwarfs emit over their lifetime, known as their luminosity evolution, is quite drastic.

Over its lifespan, our Sun will change its luminosity by about 30% (before then evolving into a giant star).

However, a red dwarf may change its luminosity 10-fold!

So, a planet in the habitable zone of a red dwarf now was probably once scorching hot, and in the future will be freezing cold.

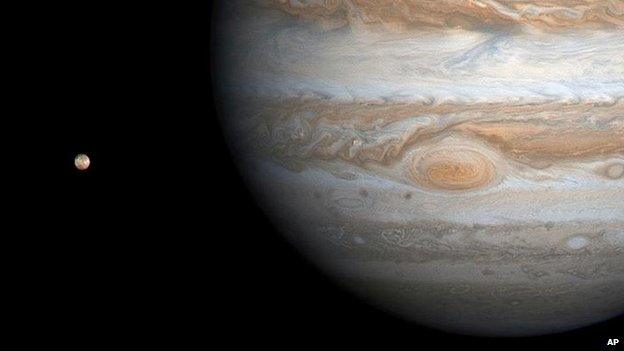

Does Jupiter (seen here beside its moon Ganymede) stop more asteroids hitting Earth?

I haven't even begun discussing some of the "rare-Earth" arguments that point out a range of factors that affect the Earth that may be necessary for life, but that may be rare for other planets.

These are things like the presence of Jupiter (which may or may not deflect asteroids and comets from striking the Earth) or the presence of the moon (which may stabilise Earth's spin).

This may seem all doom and gloom, but I only mean to highlight the difficulties in defining what might be a "habitable" planet; not that I don't think there are any out there, or that we can't find them.

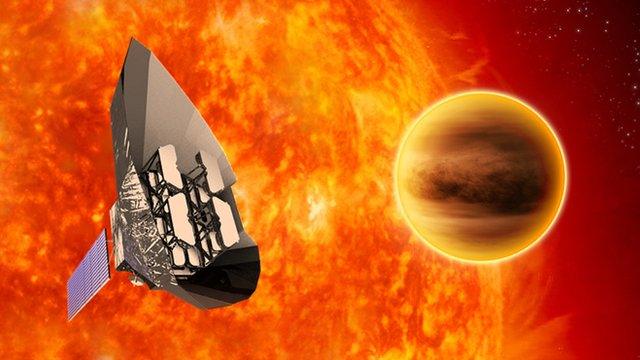

Exciting projects, such as the European Space Agency's Plato mission (due to launch in 2024) aim to find Earth-sized planets, in Earth-like orbits, around nearby Sun-like stars.

These are the type of rocky planets that would be ripe for follow-up, ultimately opening the possibility for probing directly for biomarkers in their atmospheres.

Just over 20 years ago we didn't know of ANY planets beyond our Solar System (we now know of thousands of candidates!) and only in the last few years have we been able to find small, rocky alien worlds.

The pace of discovery is astonishing and in 20 years' time I suspect I will look back at this article and find I was totally wrong about everything.

This is what progress is.

Dr Christopher Watson is senior lecturer in extrasolar planets and low-mass stars at the Astrophysics Research Centre, Queen's University, Belfast

- Published27 January 2015

- Published24 September 2014

- Published20 February 2014

- Published22 October 2013

- Published6 February 2013