Modelling the spread of hospital bugs

- Published

Computer modelling shows how droplets can spread in a typical four-bed ward (video courtesy University of Leeds)

A new computer model predicts that multi-bed hospital wards increase bacterial hand contamination by 20% compared with single-bed wards.

Understanding exactly how bacteria spread could improve the way we design and clean our hospitals, and train healthcare workers.

Researchers from the University of Leeds presented their findings at the British Science Festival in Bradford.

Healthcare acquired infections affect one in every 15 hospital patients.

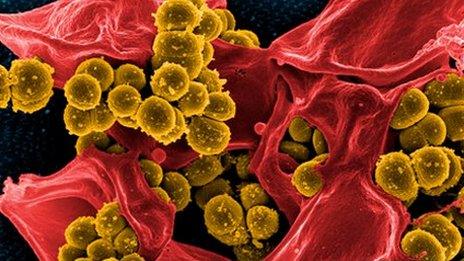

They include the "superbug" MRSA and the seasonal norovirus vomiting bug.

It is estimated that these infections cost the NHS an estimated £1bn annually and cause around 5,000 deaths.

Adequate hand washing by healthcare professionals and deep cleaning of infected rooms by hospital "bug-buster" teams and equipment are amongst the tactics employed to drive down the infection rate.

End of the line?

Some strains of bacteria now are unharmed by nearly all the drugs designed to kill them.

It's conceivable that in 20 years, simple surgery will become impossible because it relies on antibiotics.

The Leeds researchers have now developed a quantitative model to predict how the design of the hospital can affect the spread of infection.

"We combined data from mathematical modelling, data from hospitals and very controlled lab experiments to predict what will happen if somebody coughs, where the particles will land and contaminate and who might touch those surfaces and what does that mean for risk of transmitting infection," explained Dr Marco-Felipe King.

He and his colleagues have been able to develop a predictive model that estimated the number of bacteria that would remain on the healthcare worker's hands - even with handwashing.

They predict that levels of contamination are 20% higher on the hands of healthcare workers in multi-bed rooms compared to single-bed rooms.

They also observed that bacteria were likely to spread many metres from the source - and potentially into the bed-space of other patients.

In a multi-bed ward this could mean that bugs are spread by a healthcare worker even if they wash their hands after each patient interaction, as the bugs could be waiting for them on the next patient's bedside table.

How far do infectious droplets spread when somebody sneezes?

The evidence that single-bed rooms are superior for infection control is not new. But they are not generally feasible, financially and practically.

Information from the predictive model could help change the way we clean our hospitals - a sort of "evidence-based cleaning".

The team hopes to combine this modelling with their current work on real-time airflow simulations. Dr Marco-Felipe King explained that they are "going to combine the modelling of airflow patterns of hospital rooms, building design, surface contamination and that's going to inform the future of hand hygiene and surface cleaning programmes".

Professor Noakes added: "Our next step will be to look at how we can use this to look in more detail at infection risk and how we can re-design buildings to improve things for patients".

Dr Lena Ciric, who manages the Healthy Infrastructure Research Group at University College London, said this was valuable work.

"Computer models are an important tool in the study of the spread of healthcare associated infections, especially when they are validated using clinical data," she told the BBC. "They can be used to make improvements in the design of hospital wards and to change the behaviour of healthcare staff in order to reduce infection rates."