Next two years hottest, says Met Office

- Published

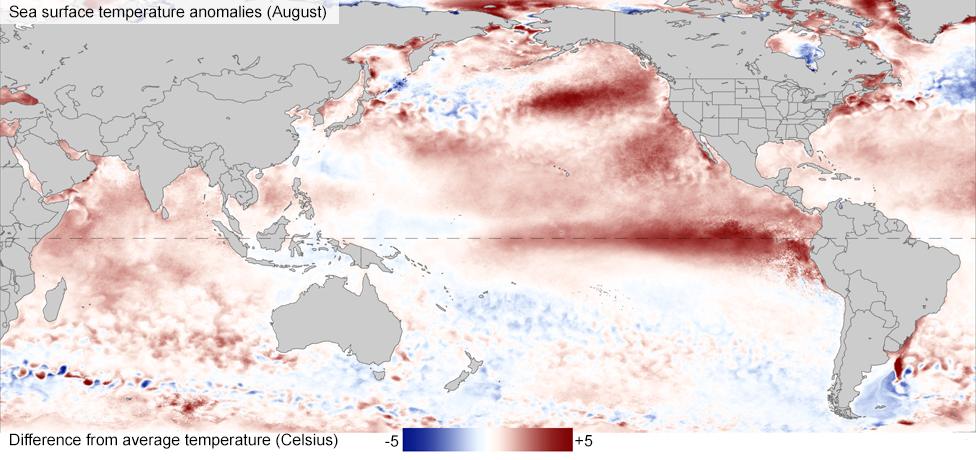

The El Nino phenomenon sees surface waters warm dramatically in the eastern Pacific

The next two years could be the hottest on record globally, says research, external from the UK's Met Office.

It warns big changes could be under way in the climate system with greenhouse gases increasing the impact of natural trends.

The research shows that a major El Nino event is in play in the Pacific, which is expected to heat the world overall.

But it also reveals that summers in Europe might get cooler for a while as the rest of the globe warms.

The scientists confirm that in 2015 the Earth's average surface temperature is running at, or near, record levels (0.68C above the 1961-1990 average).

Tomasz Schafernaker says the El Nino that is underway could be the strongest since 1950

Volcanic caveat

Met Office Hadley Centre director Prof Stephen Belcher said: "We know natural patterns contribute to global temperatures in any given year, but the very warm temperatures so far this year indicate the continued impact of (manmade) greenhouse gases.

"With the potential that next year could be similarly warm, it's clear that our climate continues to change."

An external reviewer, Prof Rowan Sutton, from the University of Reading, confirmed: "Unless there's a big volcanic eruption, it looks very likely that globally 2014, 2015 and 2016 will be among the very warmest years ever recorded.

"This isn't a fluke. We are seeing the effects of energy steadily accumulating in the Earth's oceans and atmosphere, caused by greenhouse gases."

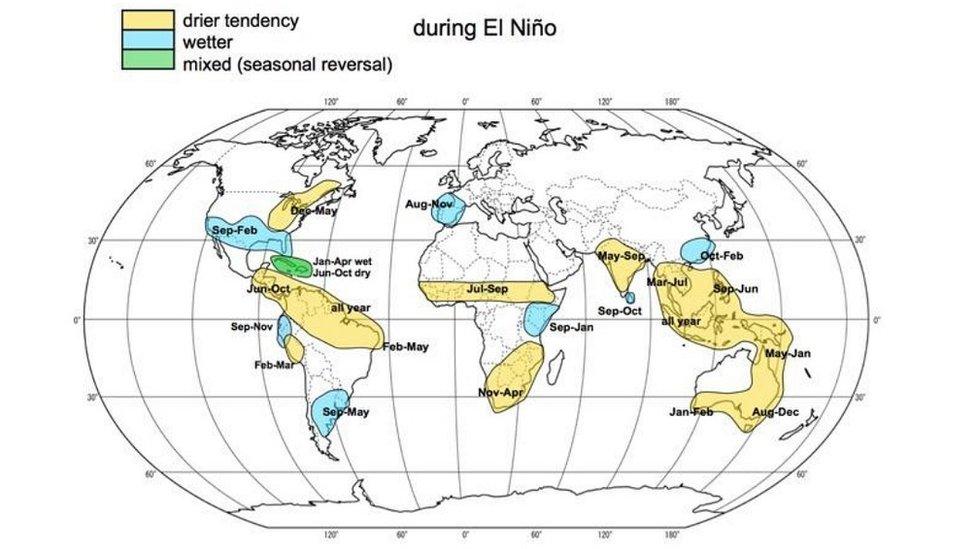

This map shows the patterns in precipitation over land favoured during El Nino events

California reprieve?

The scientists say that the combination of the effect of increasing CO2, coupled with long-term natural ocean trends, leaves the climate system looking "very interesting". They suspect major changes may be under way.

Prof Adam Scaife from the Met Office said: "It's an important turning point in the Earth's climate with so many big changes happening at once."

Two trends affecting weather patterns in the near and medium term are in the Pacific Ocean. El Nino happens when a Pacific current reverses on average every five years or so, bringing downpours where there is normally drought and drought where there is normally rain. El Nino tends to push world temperatures upwards.

This growing event is now looking similar to the 1998 El Nino, which bleached corals and brought havoc to world weather systems. The current event could increase drought risk in South Africa, East Asia, and the Philippines - and bring floods to southern South America.

One good outcome might be the end of the crippling, four-year California drought.

Arctic implication

The second natural change is a shift in the decadal temperature pattern in the North Pacific known as the PDO. It has been in a cool phase, which the Met Office says has contributed to the pause in the rise of average surface atmospheric temperatures over the past decade. Now, it is entering a warm phase, which will typically make the world hotter.

But there's another factor at play. These two warming events will be partly offset by the North Atlantic temperature pattern (AMO) switching into a cool phase.

The scientists say they have recently learned more about how these great ocean patterns temper or accelerate human-induced warming, but Prof Sutton said: "The bit we don't understand is the competition between those factors - that's what we are working on."

So the researchers can say that changes in the Atlantic mean Europe is likely to get slightly cooler and drier summers for a decade - but only if the Atlantic signal is not overridden by the Pacific signal. And they cannot be sure yet which influence will prevail.

The Atlantic cooling could lead to the recovery of sea-ice in adjacent Arctic areas.

Energy input

The Met Office is being ultra-cautious after being castigated for what some said were over-confident decadal forecasts in the past, when natural ocean trends were less well understood.

When asked when the pause in surface warming would end, they stressed that from their perspective there was no real pause in the Earth's warming because the oceans continued to heat, sea levels continued to rise and ice continued to melt.

Prof Scaife said: "We can't be sure this is the end of the slowdown, but decadal warming rates are likely to reach late 20th-Century levels within two years."

And Prof Sutton warned: "If greenhouse gas-driven warming continues unabated, the long-term effects on global and regional climate will dwarf those of short-term fluctuations like El Nino."