Paris climate summit: Don't mention Copenhagen

- Published

- comments

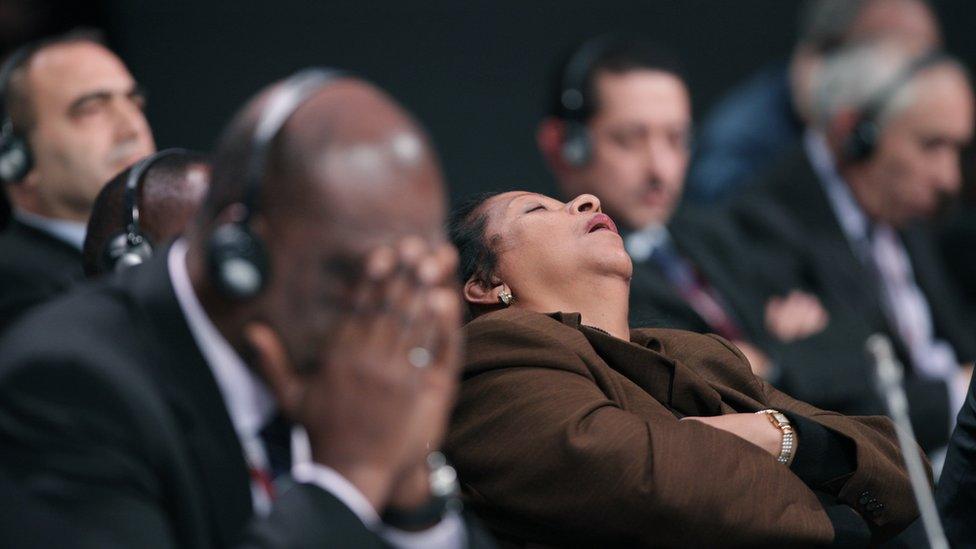

The failures of the Copenhagen summit loom large over Paris

For officials and politicians getting ready for the UN summit on climate change in Paris later this year, there's a word that dare not be uttered: Copenhagen.

I remember pained faces etched with failure on the final day of a dysfunctional gathering in the Danish capital in 2009, the last time world leaders got together to try to tackle global warming, and the collective memory still haunts the process six years on, external.

So, in the run-up to the next big attempt to secure a global treaty limiting greenhouse gases, it's worth exploring what's changed since 2009 - and what hasn't.

In some ways, the negotiating landscape is transformed, mainly because of dramatic shifts by the two biggest emitters, the United States and China.

President Obama spoke of the threat of global warming from his first day in office but he was distracted by healthcare in his first term and came to Copenhagen with his hands tied by a reluctant Congress.

But now, as he eyes a chance to leave the White House with a green legacy, he can point to his plan to reduce emissions from power stations as tangible evidence of American willingness to take the issue seriously.

That plan is facing determined opposition from coal states - and may well be dismantled if the next presidential election brings in a Republican - but for the moment it shows the United States in a more constructive light around the negotiating table.

China too is in a different place compared to its role in Copenhagen - which many witnesses there saw as more or less openly obstructive.

China on board

After years of resisting any attempt to be included in an international system of carbon targets, the Chinese leadership is now openly talking of national emissions peaking around 2030, if not before - something that would have been unimaginable amid the chaotic scenes of Copenhagen.

The motivation is more to do with the filthy air choking many Chinese cities - and the increasingly vocal complaints about it from a growing and emboldened middle class - than with climate change itself. On a visit to China two years ago, the pollution was so dense it closed an airport I was trying to fly from for several hours.

But, whatever the reason, China comes to the talks in Paris using language that could suggest a new willingness to see a global deal.

Another big change from 2009 concerns technology: the prices for renewables have fallen so dramatically in many parts of the world that a future involving clean energy like wind and solar looks far more feasible than it once did. China is playing a leading role in that.

And, last but not least, the UN process itself has been upended. Whereas in Copenhagen there was an effort to browbeat countries into accepting targets for reducing carbon emissions, Paris is about collecting voluntary plans for action drafted by individual countries.

In the jargon - which we'll hear a lot more of - the UN is inviting each government to submit what is called an Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC). In plain English, that means a pledge to do something. The details are here, external.

So far some 62 countries have tabled their INDCs - covering a little over 60% of global emissions - among them the big guns of the United States, China and the EU.

By the time Paris starts on 30 November, there's a hope that even more of these plans will have come in, covering perhaps 85% of emissions - those from India, Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia are eagerly awaited.

Closer scrutiny

In itself, that could be seen as remarkable progress - just getting so many governments, some very unwilling, even to take part in such a public process.

But closer scrutiny starts to reveal a serious problem. Add up all these pledges and - no surprise - there's a big shortfall compared with what the scientists of the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change say is needed.

The UN Environment Programme estimates that if everyone keeps burning fossil fuels as usual, then a global average temperature rise, compared with the pre-industrial age, of 3C by the end of the century seems likely.

The INDCs submitted so far might reduce that to a likely rise of something like 2.5C by 2100, which is still above the internationally accepted target of 2C.

That emissions gap gives a hint of difficult hurdles to come. If the current pledges aren't adequate, there's a plan for the Paris deal to spell out a system of five-year reviews to try to use peer pressure to ratchet up everyone's efforts - but the detail of that is the subject of fierce haggling.

So too is the age-old and fraught question of money - with poor countries long cynical about rich-world promises of $100bn a year to help them adapt to climate impacts and to transition to green forms of growth. So far, some $31-37bn is on the cards. That may rise but disappointment would seem inevitable.

And hanging over the whole endeavour is the most fundamental challenge of all: Agreeing on a system that everyone will see as fair for sharing out the burden of carbon cuts - what is called Common But Differentiated Responsibility.

Is the onus on developed countries, which have enjoyed a century or more of emitting greenhouse gas, or the giant, rapidly industrialising nations whose emissions are likely to keep soaring? Or a mix of each? We'll hear much more about that dispute, too.

Asked about the chances of success at the talks, UK government sources say they expect a deal to be done but also that "it's not in the bag".

Paris might not be "another Copenhagen" but it definitely won't be easy.

Follow David on Twitter, external.