Fresh views of Ceres but 'spots' remain mysterious

- Published

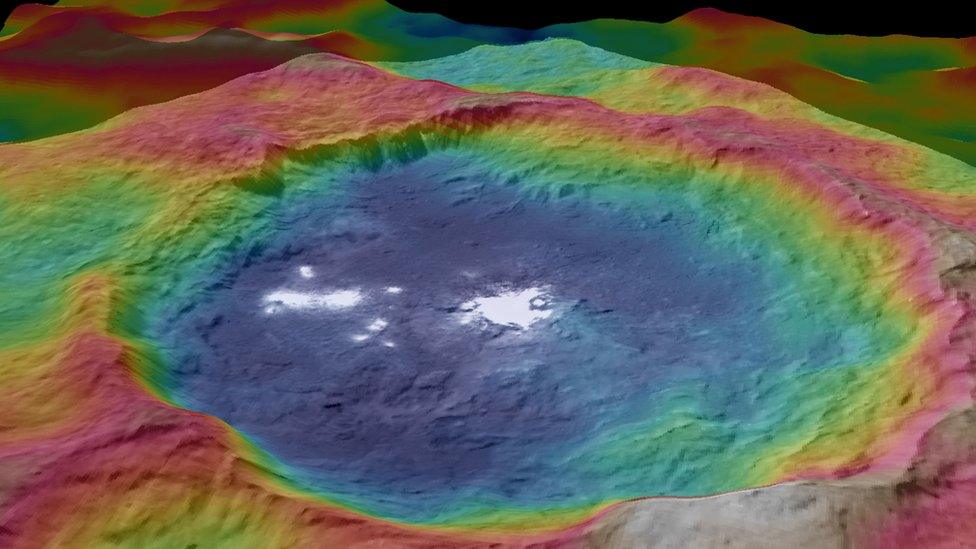

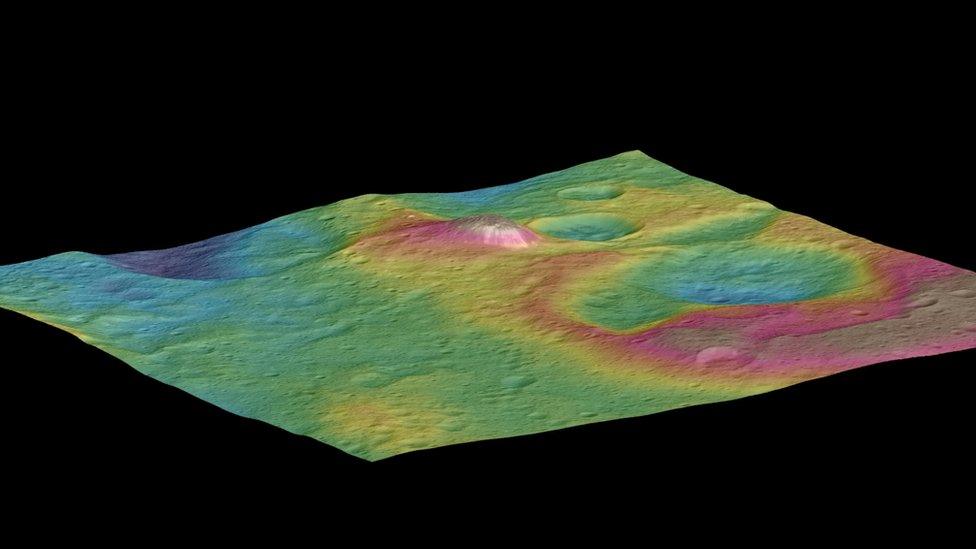

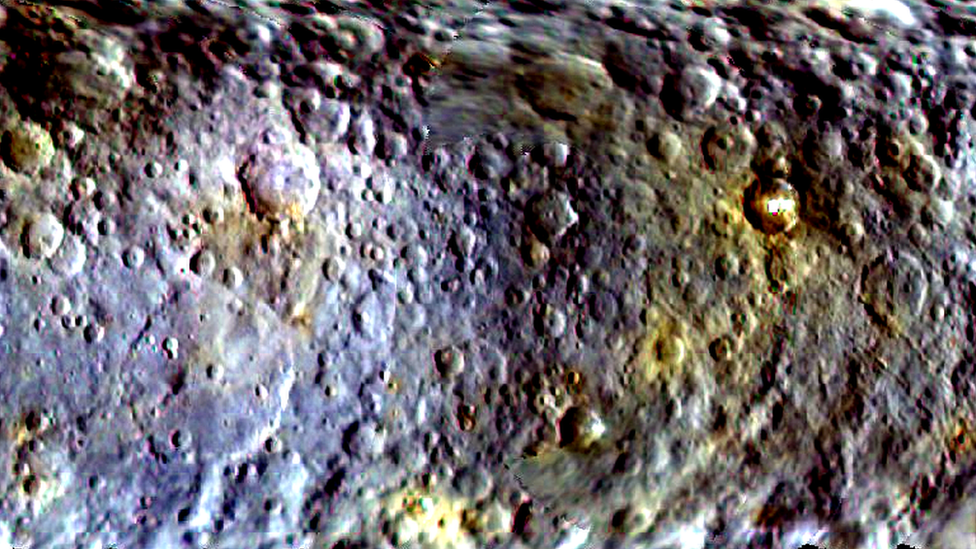

The Occator Crater, colour-coded to show differences in elevation, and its baffling bright spots

The team behind Nasa's Dawn mission to Ceres has released striking new images, but remains unable to explain the dwarf planet's most intriguing mystery.

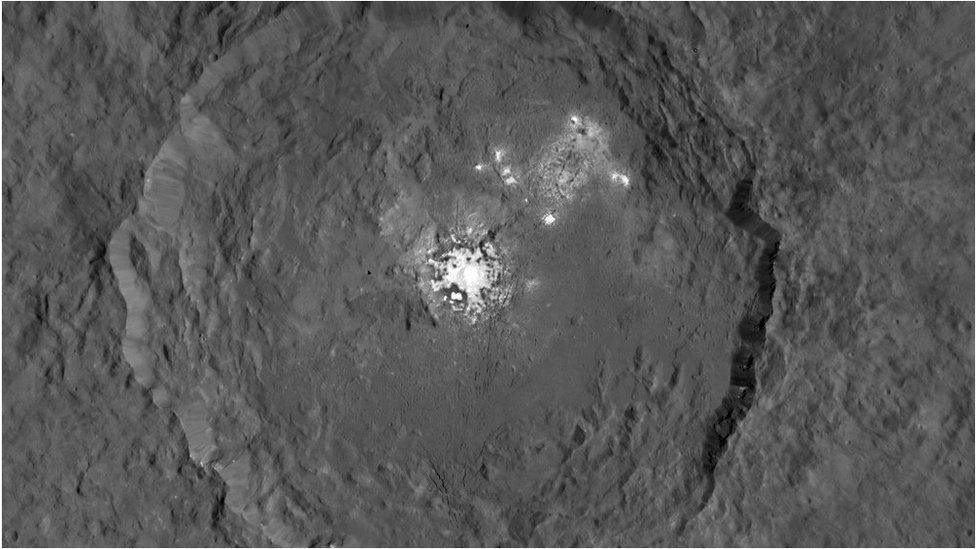

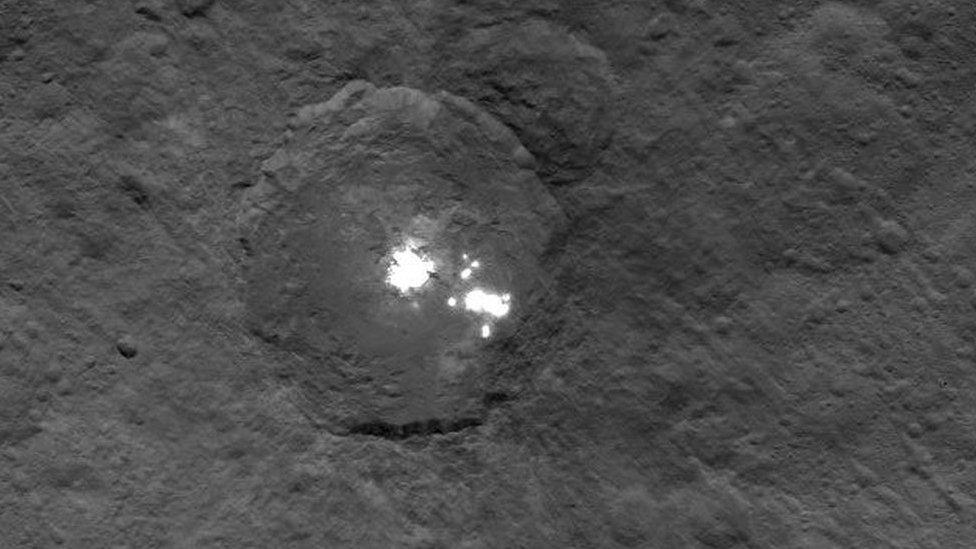

Bright spots within a 90km-wide crater have baffled scientists since the probe spied them on its approach.

Now in orbit around Ceres, Dawn is gathering detailed data about the world's geology and its composition.

Mission researchers described the latest images at the European Planetary Science Congress, external in Nantes, France.

Currently, their best guess to account for the spots is an expanse of some type of salt - but this is speculation.

"We haven't solved the source of the white material," said the mission's principal investigator Chris Russell from the University of California Los Angeles.

"We think that it's salt that has somehow made its way to the surface. We're measuring the contours, trying to understand what the surface variations in that crater are telling us."

Ceres is a 950km-wide dwarf planet sitting in the Solar System's asteroid belt. Dawn is currently orbiting it at a distance of 1,470km and imaging the entire surface every 11 days.

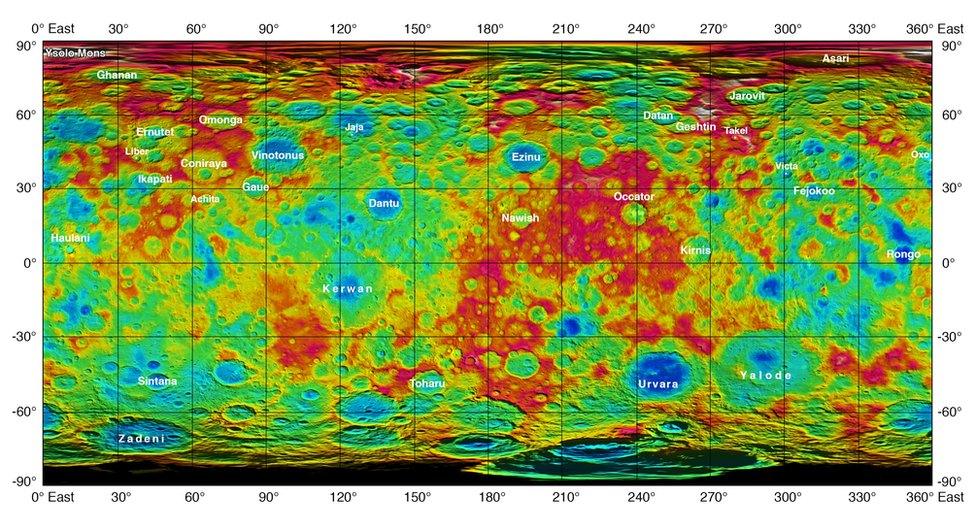

This height-coloured map of Ceres has a resolution of 400m per pixel. The bright spots are in the Occator Crater (centre-right)

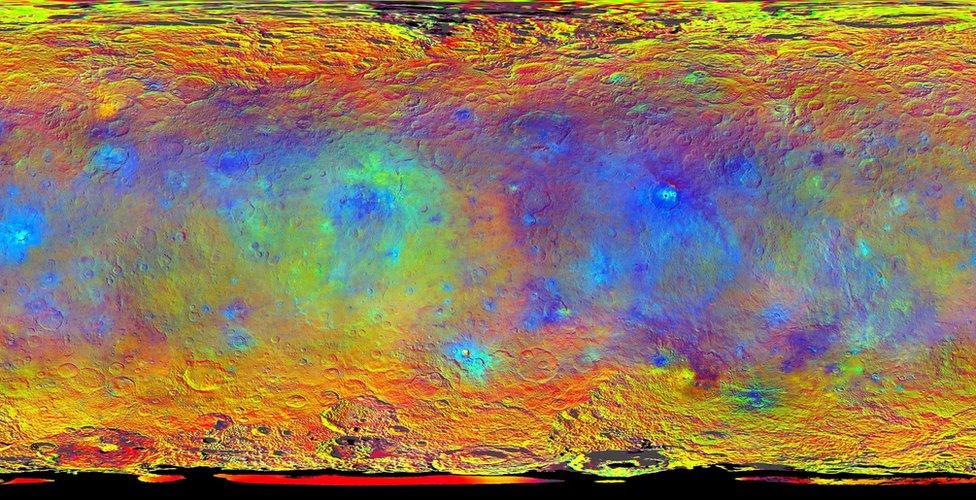

These "stretched" colours give clues about Ceres' mineral composition

It was eight years ago this week, external that Dawn blasted off on its mission from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

Before arriving at Ceres six months ago, the spacecraft dropped in on the asteroid Vesta for just over a year in 2011 and 2012.

The latest release of data includes a new topographic map, showing the shape of Ceres' entire surface in the most detail yet.

"The irregular shapes of craters on Ceres are especially interesting, resembling craters we see on Saturn's icy moon Rhea," said deputy mission chief Carol Raymond from Nasa's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. "They are very different from the bowl-shaped craters on Vesta."

There is also a colour-enhanced mosaic image that offers clues about what the dwarf planet is made of - arguably asking more questions than it answers.

"There's an interesting blue ring here," Prof Russell told a media briefing at the conference. "We have absolutely no idea what that blue ring is due to.

"And there are streaks across the surface that point back to the Occator Crater with its bright spots. We are poking at this, and we're looking for ideas, but we haven't solved the problem yet."

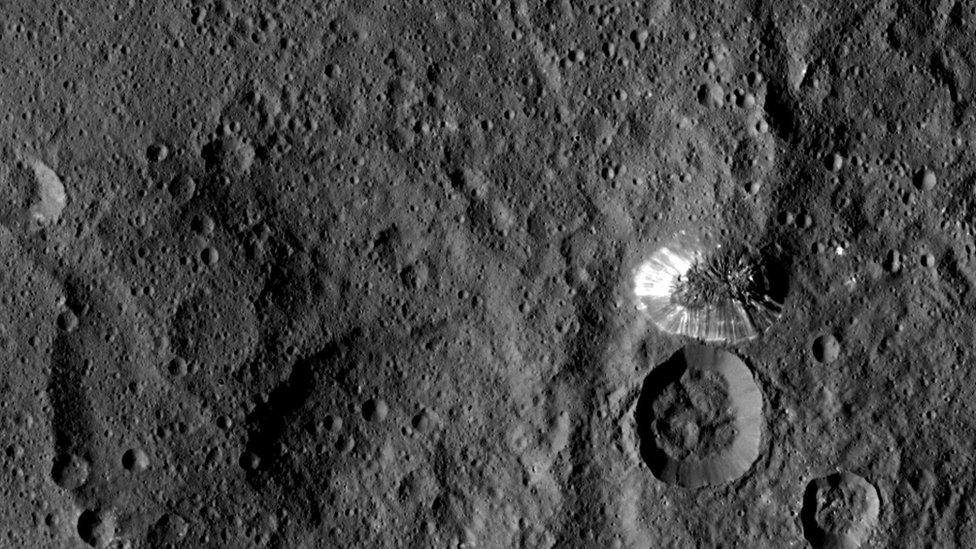

Another new height-coloured image describes the contours of this strange mountain

This earlier photo showed the mountain - which is yet to be named - from above

An oddly shaped mountain that towers 6km above relatively flat surrounding terrain is also puzzling the team, Prof Russell added, because it does not look like the result of known geological processes.

"We're having difficulty understanding what made that mountain," he told reporters.

In October, Dawn will start dropping to its final target altitude of 375km for an even closer look at Ceres. This will be its final home. Even after it ceases operations in mid-to-late 2016, the probe is expected to stay in this stable orbit and become a permanent fixture in the dwarf world's sky.

"We're not going to leave Ceres. We're going to stay in Ceres orbit forever," Prof Russell said.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published9 September 2015

- Published10 June 2015

- Published13 April 2015

- Published20 March 2015

- Published6 March 2015

- Published2 March 2015

- Published5 February 2015

- Published27 January 2015

- Published19 January 2015