New lithium-air battery design shows promise

- Published

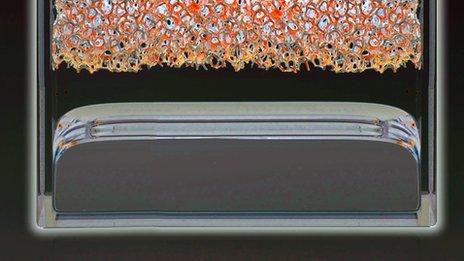

The demonstration batteries were tested in sealed flasks, to surround them with pure oxygen and controlled humidity

A new design for lithium-air batteries overcomes several big hurdles that have stood in the way of this concept.

Lithium-air cells can store energy much more densely than today's lithium-ion batteries, making them particularly promising for electric cars.

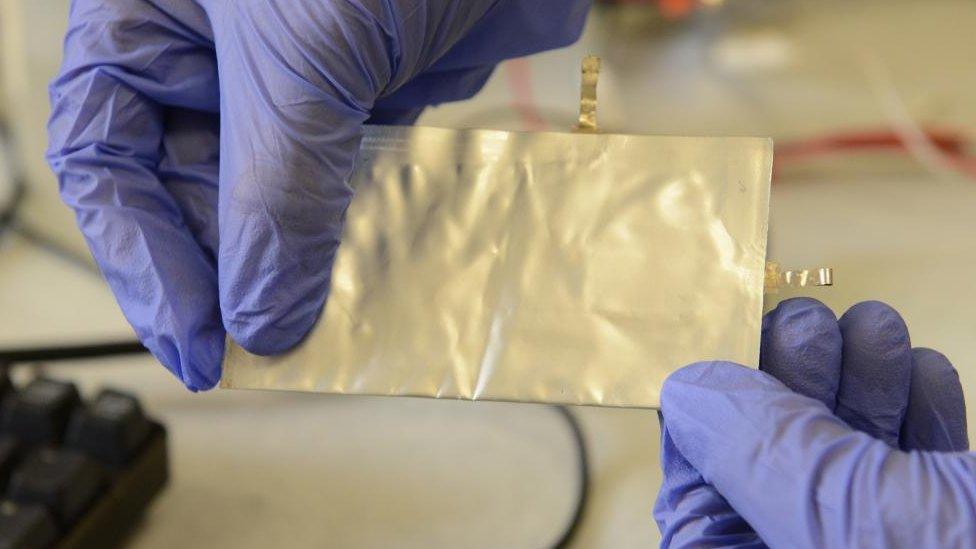

The design, published in Science, external, uses a spongy graphene electrode and a new chemical reaction to drive the cell.

It loses much less energy and can be recharged many more times than previous attempts at lithium-air batteries.

The hope for lithium-air batteries is that they will take in regular air to fuel the chemical reaction that releases electricity: lithium ions move from the positive electrode to the negative one, where they are oxidised.

At present the engineers behind the new effort, at the University of Cambridge, have only made laboratory test units which operate in pure oxygen, rather than air.

In a first, however, the prototypes can operate when that oxygen is moist.

"What we really want is a [true] lithium-air battery - one that just takes in air, without having to remove CO2, nitrogen and water," Prof Clare Grey, the senior author on the study, told BBC News. "And now we have a system that at least tolerates a lot of water."

Despite the significant progress made by Prof Grey's team, they say a commercial lithium-air battery is at least 10 years away.

Electric cars today mostly use lithium-ion batteries, not too dissimilar from those in laptops and smartphones

Their demonstration units, for example, are still rather sluggish.

"Our batteries take days to charge and discharge, when you want it to happen in minutes and seconds," Prof Grey explained.

But the design has major pluses.

'New way of thinking'

It packs in energy at a density that is almost the theoretical limit for lithium-air batteries. That energy density is what will eventually send electric cars across countries, rather than cities, on a single charge.

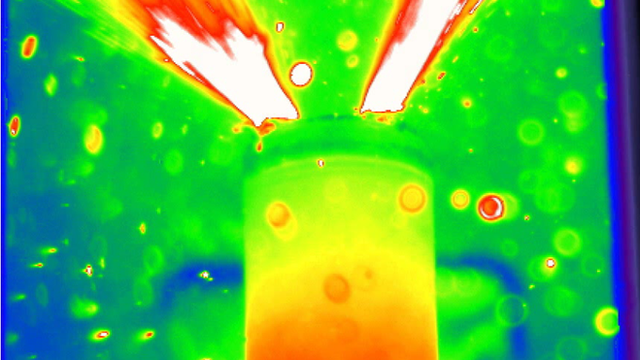

It also charges at a voltage of 3.0 and discharges at 2.8 volts - an efficiency of 93% - meaning it loses surprisingly little energy as heat. This is close to the efficiency of current lithium-ion batteries, and a big improvement on previous lithium-air efforts.

And crucially, these test batteries can be charged and recharged more than 2,000 times, with little effect on their function.

"We've been able to cycle our cells for months, with very little evidence of side reactions," Prof Grey said.

Waseem Mirza reports on the research for BBC Look East

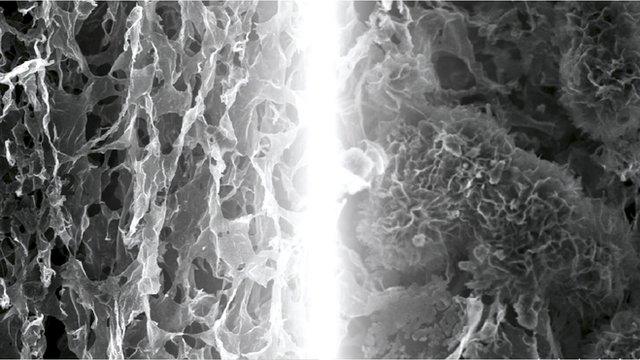

Part of the reason for this success is the design of the cathode, which is made from a sponge-like arrangement of graphene. This so-called "wonder material" is built up from one-atom-thick sheets of carbon.

The holes in the porous cathode allow reaction products to build up, as the battery discharges, and then dissolve away again as it gets recharged.

Also critical is the chemical reaction itself. Prof Grey's team has used an additive, lithium iodide, to change the chemistry at the heart of the battery.

Instead of lithium peroxide (Li2O2), as in most other lithium-air designs, the discharging reaction produces lithium hydroxide (LiOH) at the cathode.

And that lithium hydroxide can be completely dissolved away again, when the battery is recharged and the lithium ions return to the anode.

As the battery releases energy, the spongy structure of the graphene electrode (left) accumulates deposits of lithium hydroxide (right)

"It's a very different chemistry; it gives a new way of thinking about it," said Prof Grey. "It's a way off being commercial, but it does provide some interesting new directions to study."

Dr Paul Shearing, a chemical engineer at University College London, said the Cambridge design was "an important step" towards taking lithium-air batteries out of the lab.

"It's very impressive work," he told the BBC.

"Lithium air batteries [have been] plagued with problems, particularly around poor cycle life. This potentially could address those problems."

If successful, Dr Shearing added, lithium-air batteries could make a huge difference because their energy density very nearly matches the energy-per-kg packed by petrol.

As Prof Grey put it: "It's the energy density that's going to make that car battery that gets [from London] to Edinburgh."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published1 May 2015

- Published28 April 2015

- Published7 April 2015

- Published21 September 2014