EU to give 7m euros in fight against olive tree killer

- Published

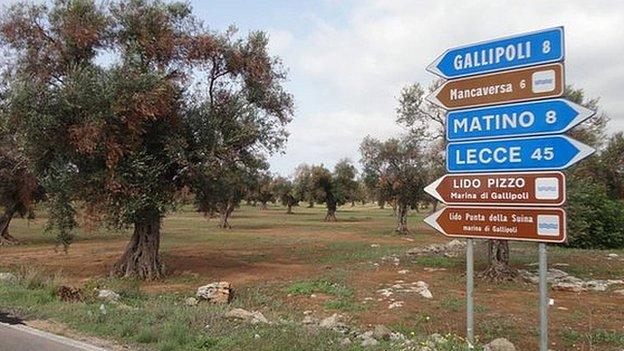

The invasive pathogen has affected thousands of hectares of olive plantations in Puglia, southern Italy

The European Commission says it will provide seven million euros (£5m) to fund research into a disease that poses a "very serious threat" to olive trees.

The announcement was made at a scientific workshop in Brussels that focused on the most effective ways to tackle Xylella fastidiosa.

First recorded in southern Italy in 2013, the disease has since been detected in southern France.

Experts describe it as one of the "most dangerous plant pathogens worldwide".

The funding, which comes from the EU's Horizon 2020 programme, external, is part of the effort to tackle the agent before it spreads more widely to other key olive-producing regions within Europe.

Globally, the EU is the largest producer and consumer of olive oil. According to the European Commission, the 28-nation bloc produces 73% and consumes 66% of the the world's olive oil.

Closing the gaps

The workshop, convened by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) on behalf of the Commission, was designed to bring together the world's leading experts on the disease in order to help identify where further research was needed.

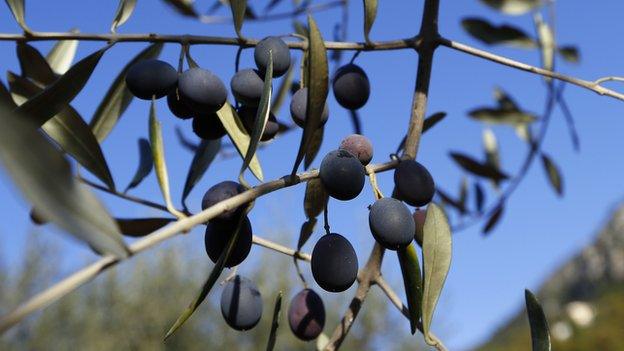

Olive production forms an important part of many European regions' economies

"The outcomes from this workshop could help steer where the money should go in terms of the most pressing aspects of the issue," a EFSA spokesman told BBC News.

Speaking after the two-day workshop, one of the scientists - Stephen Parnell from the University of Salford, UK - said that there had been a particular focus on surveillance and improving ways to detect new outbreaks.

"This is a key area for researchers; how do we monitor the epidemic?" he told BBC News.

"What research do we need for more advanced methods of detection and how do we improve our ability to detect the pathogen, because it is very good at hiding from us so we need very good detection methods.

"We also discussed how we targeted our inspections on a larger scale so we are looking in the right place."

Since it was first detected in olive trees in Puglia, in southern Italy, in October 2013, it has since been recorded in a number of other locations, including southern France. To date, it has yet to be recorded in Spain, the world's largest olive oil producer.

Experts warn that should the disease, which has numerous hosts and vectors, spread more widely then it has the potential to devastate the EU olive harvest.

Citrus experience

The EFSA Panel on Plant Health produced a report in January warning that the disease was known to affect other commercially important crops, including citrus, grapevine and stone-fruit.

The Xylella fastidiosa bacterium invades a plant's vessels that it uses to transport water and nutrients, causing the infected plant to display symptoms such as scorching and wilting of its foliage, eventually followed by the death of the plant.

Dr Parnell, who was a member of a working group that contributed to the EFSA report, said the disease posed a threat to the whole EU.

But he added: "The good thing about this workshop was that it was bringing in experts from places such as Brazil and the US who have a lot of experience of working with the pathogen.

"Getting them onboard means that we can learn what worked for them and how we can apply it in our own context."

The disease has plagued citrus farmers in North and South America for decades. It remained confined on these continents until the mid-1990s when it was recorded on pear trees in Taiwan.

According to the European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organisation (EPPO), the pathogen had been detected by member nations on imported coffee plants from South America. However, these plants were controlled and the bacterium did not make it into the wider environment.

- Published9 January 2015

- Published24 March 2015

- Published2 September 2015

- Published30 July 2015