The hunt for Albert Einstein's missing waves

- Published

On the trail of Albert Einstein's missing waves

In the Italian countryside, not far from Pisa, a vast experiment is about to be switched on.

If it's a success, one of Albert Einstein's greatest predictions will have been directly observed for the first time.

If it fails, laws of physics might have to be reconsidered.

The experiment is called Advanced Virgo, and it will be hunting for the most elusive of astrophysical phenomena.

"Maybe we have the opportunity for the first time to detect gravitational waves on the Earth," explains Dr Franco Frasconi, from the University Pisa, who is part of Virgo's international team.

"This would be a clear demonstration that what [Einstein] said 100 years ago is absolutely correct."

What is general relativity? Toby Wiseman explains

On 25 November 1915, Albert Einstein presented the final version of his field equations to the Prussian Academy of Sciences.

They underpinned his Theory of General Relativity - a pillar of modern physics that has transformed our understanding of space, time and gravity.

From it, we have been able to understand so much - from the expansion of the Universe, to the motion of the planets and the existence of black holes.

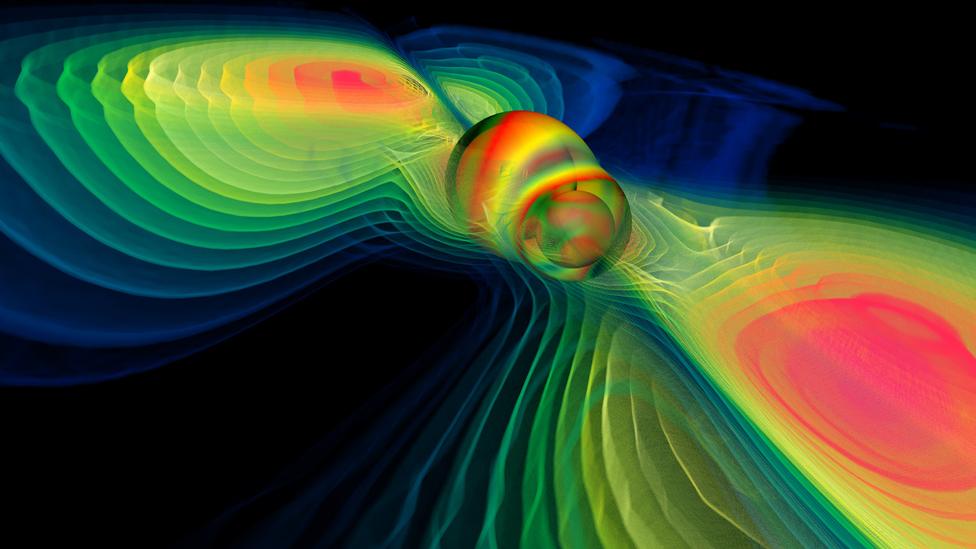

But he also proposed the presence of gravitational waves, essentially ripples of energy that distort the fabric of space-time.

Think of them as a bit like the waves that radiate out when you throw a stone into a pond.

Any object with mass should generate them when it's on the move. Even us. But the greater the mass, and more dramatic the motion, the larger the waves.

And Einstein predicted that the Universe was awash with them.

Ripples in the fabric of space-time

The waves are an inevitable consequence of the Theory of General Relativity

Their existence has been inferred by science but not yet directly detected

They are ripples in the fabric of space-time produced by violent events

Accelerating masses will produce waves that propagate at the speed of light

Detectable sources ought to include merging black holes and exploding stars

Virgo bounces laser beams down tunnels; the waves should disturb the light

Detecting the waves opens up the Universe to completely new investigations

But while astronomers have indirect evidence for their existence, getting a glimpse of these cosmic curiosities has not yet been possible.

Physicist Dr Toby Wiseman, from Imperial College London, UK, explained: "I'm not surprised we haven't directly seen gravity waves yet.

"Gravity is actually the most feeble of the forces and even dramatic astrophysical sources only emit weak gravity waves."

Now, in Italy, scientists hope to find them. But it won't be easy.

The first incarnation of the Virgo experiment ran from 2007 - and didn't see anything. Neither did its US-counterpart, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (Ligo).

But both machines - called interferometers - are now undergoing expensive upgrades, and the teams hope major improvements in sensitivity could hold the key to success.

The experiment in Italy is formed of two 3km-long arms

Dr Frasconi explained: "The technology available to detect gravitational waves is available just today.

"During the last 10 years, we have developed very sophisticated technology to construct this kind of interferometer."

The scientists are attempting to spot the tiny distortions created when gravitational waves pass through the Earth.

They are hoping to see those emanating from violent cosmic events, such as exploding stars or colliding black holes.

iWonder: Does Einstein's general theory of relativity still matter?

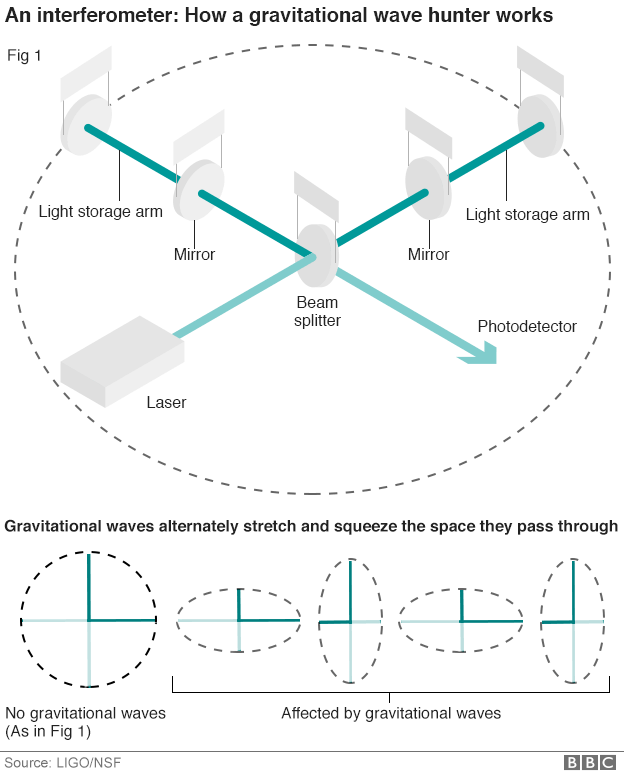

The Virgo detector is formed of two identical 3km-tunnels, in a giant L-shape formation.

A laser beam is generated, then split into two - with one half being fired along one tunnel, and the other half surging through the second tunnel.

Mirrors at either end send the lasers travelling back and forth many times, before they are recombined.

This might seem elaborate, but it takes advantage of a handy property of lasers - the fact that they are intense beams of light, and light is a wave.

Imagine if two waves in the ocean crashed into each other, while one was at a peak, and one was at a trough - the waves would cancel each other out.

The same is true inside the experiment. And if the waves have travelled exactly the same distance along the two tunnels, then they cancel each other out, producing no signal.

However, if a gravitational wave has travelled through the tunnel, it will very subtly distort its surroundings, changing the length of the tunnels by a minute amount - just a fraction of the width of an atom.

And the way the waves move through space-time means that one tunnel would be stretched and one squeezed, which would result in one laser travelling a slightly longer distance while the other would have a shorter journey.

As a result, the split beams will re-combine in a different way: the waves of light will interfere with each other, rather than cancelling out - and scientists will detect a signal.

Great efforts have been made to insulate the experiments from the general rumbles that pervade the Earth, from traffic noise to earthquakes.

"You are trying to a build a machine to avoid potential noise," says Dr Frasconi.

"This machine is anchored directly on the ground floor - and the ground floor typically vibrates. The most important challenge is to isolate the mirrors.

"For Virgo, this is the most important challenge. From the beginning we have spent a lot of time to develop the multistage pendulum to isolate the mirrors from seismic noise."

Advanced Ligo in the US will also detect gravitational waves as they pass through

But even then, a signal in Italy will not be enough.

If a gravitational wave is spotted there, the upgraded Advanced Ligo in America, which has the same set-up as Virgo, but is made up of two detectors with 4km-long arms, should also see the signal. So potentially should another, smaller experiment in Germany.

Advanced Ligo is now up and running, and scientists hope Virgo will be ready to be switched on by the end of the year.

The collaborating teams are so confident of success that they're forecasting that 1 January 2017 will be the day the breakthrough is made.

This prediction may be a little tongue in cheek, but Dr Frasconi, who has been working in this field for two decades, is confident that the end of the search is near.

"Right now, it is extremely important to detect for the first time on Earth gravitational waves. Otherwise we do not have the right information, the right knowledge of the rest of the Universe."

A laser is fed into the machine and its light is split along two paths

The separate beams bounce back and forth between damped mirrors

Eventually, the two light paths are recombined and sent to a detector

Gravitational waves passing through the lab should disturb the set-up

Theory holds they should very subtly stretch and squeeze its space

This ought to show itself as a change in the lengths of the light arms

The photodetector hopes to capture this signal in the recombined beam

If the waves do not show up now it will mean that the experiments may need to be redesigned. And in the most extreme case, perhaps physicists might have to rethink the way that the Universe works.

But a direct glimpse will open a new window on the cosmos - one that wouldn't have been possible without Einstein.

Dr Wiseman, from Imperial College London, explains: "Seeing gravity waves would be fantastic confirmation of our understanding of general relativity.

"We have good reason to think they exist, but we can't be sure we have understood general relativity correctly until we see these ripples in space-time directly.

"Observing them would allow us new ways to test general relativity, but also give us an entirely new tool for observing some of the most fascinating objects in our Universe."

Follow Rebecca on Twitter, external

- Published19 September 2015

- Published4 September 2015