Flex satellite will map Earth's plant glow

- Published

An orchid leaf is illuminated by blue light and the red fluorescence glow is made visible by a special red filter on the camera

The European Space Agency is going to build a spacecraft to map the red glow emitted by Earth's plants.

Known as Flex, the mission was approved by member states on Thursday and will likely launch by 2022.

The satellite will carry a spectrometer to catch the subtle but telltale fluorescence that organisms produce when they engage in photosynthesis.

Scientists say this signal can be used to monitor the condition of croplands and forests.

Changes in the light emission, which is detected in the red and far-red part of the electromagnetic spectrum, will reveal, for example, if vegetation is being stressed, perhaps because of overheating, drought or disease.

Given the fundamental role played by photosynthesis in biology, there is arguably no measurement more significant than the one Flex is going to try to capture from orbit.

"We will be monitoring the core of the most important process that sustains all life on Earth," said Uwe Rascher, external, a leading figure on the mission science team.

Rival ideas

Flex is the latest concept in Esa's Earth Explorer series, external.

These are satellites that are designed to health-check the environment using novel instrument technologies.

Missions already flown have mapped Arctic sea-ice, traced ocean circulation, and quantified the amount of water bound up in soils.

Flex (Fluorescence Explorer) (PDF), external was green-lit as the eighth spacecraft in the series by the agency's Earth Observation Programme Board, meeting in Paris.

It won approval following a detailed assessment by scientists and engineers, who put it ahead of a rival proposal called CarbonSat (PDF), external.

This would have plotted the movements of carbon dioxide and methane through the atmosphere.

Although a loser on this occasion, CarbonSat may yet find support in a European Union-funded space programme.

Certainly, Esa officials would like to continue technology developments on its instrument to try to mature its design.

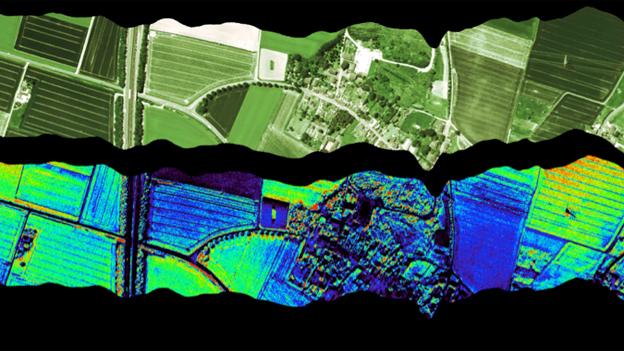

Aeroplane test of Flex concept: The colours code for different fluorescence intensities, which indicate the efficiency of photosynthesis

Plant fluorescence has been detected from orbit before, but not at the level of detail envisaged for Flex.

Leaf photosynthesis – the production of life-sustaining sugars from CO2 and water – dumps some of the energy not required in the biochemical process in the form of light.

This "waste emission" radiates from the vegetation around a couple of peaks in wavelength between 640 and 800 nanometres – on the boundary between the visible and the infrared.

The nature of this signal describes directly the efficiency of the photosynthetic process, and if Flex can characterise it accurately it will be able to discern the physical condition of plants.

"If you have water-limitation in agriculture – at the moment, we can only see it late, when the vegetation starts to wilt: when it gets brownish, yellowish and begins to drop leaves," explained Prof Rascher.

"With a fluorescence signal we see the limitation of photosynthesis because of water stress immediately when it occurs. So, we see the signal before the plant shows visible damage," the Jülich Research Centre scientist told BBC News.

The technique does require some ancillary data - in particular, a measure of the temperature of the vegetation being studied.

To get this information, Flex would fly in close formation with another satellite already dedicated to the purpose.

This would be the EU's Sentinel-3 platform, which will soon start mapping the surface temperature of the entire globe.

Cost control

Esa will initially invite industry to build only the instrument for Flex. Once it is satisfied this is on track, it will lay a contract for the rest of the spacecraft.

The agency hopes this two-step approach can help avoid the sort of cost overruns that occurred on previous Earth Explorer projects. A few have experienced lengthy delays when unforeseen technical challenges arose in the development of their novel instruments.

As for CarbonSat, there is a desire for Europe to have some kind of space-borne carbon monitoring capability – a tool to check that countries are implementing policies to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Esa officials are likely to ask member states at the agency's next big ministerial gathering to fund CarbonSat's instrument through to a prototype stage. Discussions will also be held in parallel with the European Commission about how then to fly the technology, perhaps in the next phase of the EU Sentinel programme – the suite of satellite sensors being launched by Brussels to routinely observe the Earth.

Prof Volker Liebig, the director of Earth observation at Esa, told BBC News: "The difference between the CarbonSat instrument and other measurement systems that have flown is that it wouldn't only measure 'on the point', but it would have a huge swath. So, it would have a kind of imaging capability across a couple of hundred kilometres.

"And this, in combination with its high resolution of 2km by 3km, means that we could really start to distinguish between human CO2 sources and sinks, and natural ones. And that would allow us, for example, to monitor from space the biggest power stations on Earth."

European Space Agency Earth Explorers

Goce was launched in 2009 to map the subtle variations in Earth's gravity field

Smos (above) has been studying ocean salinity and the moisture held in soils

Cryosat-2 was launched in 2010 to measure the shape/thickness of polar ice

Swarm is a trio of satellites that is currently mapping the Earth's magnetism

Aeolus is an innovative laser mission that will measure winds across the globe

Earthcare's laser will examine the role of clouds and aerosols in climate change

Biomass will have a radar to essentially weigh the carbon in Earth's forests

Flex becomes the eighth Earth Explorer and will likely launch by 2022

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external