Should politicians decide science funding?

- Published

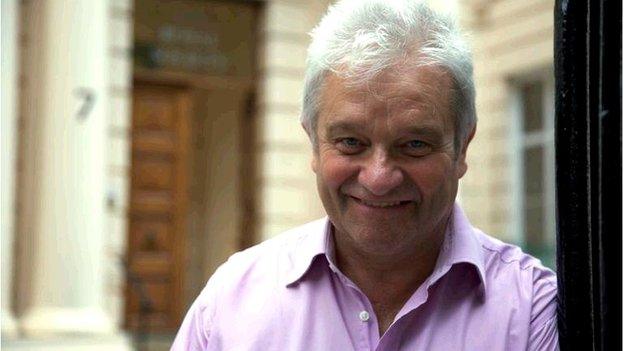

Sir Paul Nurse is the current president of the Royal Society

One of the UK's leading scientists, Sir Paul Nurse, has proposed giving politicians a greater say in the way scientific research is funded.

It would make science more important at the highest levels of government, says Sir Paul, a Nobel laureate. But he admits that what he is proposing, external could be seen as "a deal with the devil".

The government spends more than £3bn each year on scientific research.

This is allocated by seven specialist research councils, which spend on what they regard as the highest quality research without any government interference.

These range from developing new medicines, hunting for new sub-atomic particles and assessing the impact human activities are having on the environment.

It is a system that has led to the UK being one of the best countries in the world in many areas of research.

But Sir Paul believes it could be better managed if the seven research councils were run by an umbrella body called Research UK.

The aim would be to reduce bureaucracy, increase coordination and develop an overarching strategy for scientific research.

Controversially, Sir Paul believes Research UK should have input from a committee of government ministers.

Interference fear

Critics fear that this might lead to political interference in funding science and the loss of grants for areas of research that may seem obscure now - but could turn out to be scientifically important in the future.

Sir Paul, however, believes that reform is needed to "put science at the heart of government".

Under the current system, the government decides how much to spend on scientific research.

But the scientific community then determines how those funds are distributed.

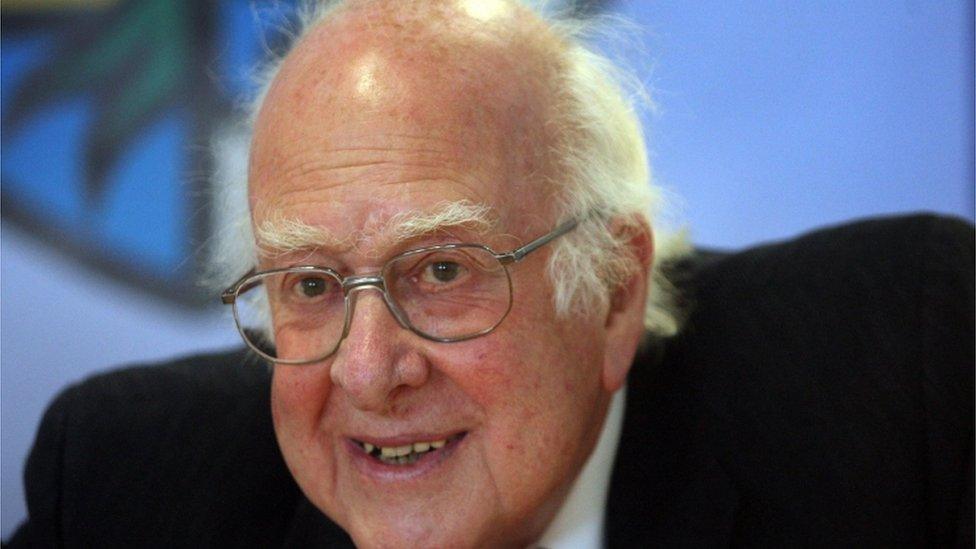

Would research - such as that into the Higgs boson particle - be at risk under the proposed system?

The so-called "Haldane principle" is that money should be spent on the best science and that decision should be determined by experts in the field.

Sir Paul believes that should continue but a more nuanced approach is now required.

The proportion of money each research council has received has remained more or less unchanged for decades.

But in that time the areas of research that each research council funds, such as physics, biology, medicine, engineering and the environment, have changed dramatically.

It may well be that research in each of these areas has accelerated equally and that it is right that the proportion of funding each receives should remain unchanged.

But the point Sir Paul is making is that even if such an assessment has been made, no-one knows about it.

There is a suspicion from outside that each separate area of the research community jealously guards the money that has been passed on to them for generations.

UK Research Councils:

Arts and Humanities Research Council

Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council

Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council

Economic and Social Research Council

Medical Research Council

Natural Environment Research Council

Science and Technology Facilities Council

Sir Paul's concept for Research UK is to create an umbrella body where such discussions can be had openly.

But what about his idea of inviting in the politicians?

He wants ministers with an interest in science to talk to officials at Research UK.

In particular, Sir Paul seems to want the Chancellor to formalise his growing interest in scientific research by chairing the group of ministers.

Is that asking for trouble?

Is there not a danger that ministers will want money spent for new labs in marginal constituencies, pet projects, and funding taken away from areas that don't match current political priorities?

Sir Paul believes they won't and that the scientific community can marshal persuasive arguments.

"Politicians are very sensible people, particularly in this country," he told me.

"We absolutely have to talk to politicians. We, as scientists, cost a lot of money and we have to justify what we do.

"We have to engage with politicians if we are to maintain the support for science which is for the public good and promotes the economy.

"We have to have a proper political discussion - and I want to promote that interface."

Proper platform

Sir Paul is an extremely nice man.

But is he in danger of thinking everyone else is as nice as him and takes the same collegiate, enlightened view as he does of the way the world works?

George Osborne says he is committed to funding science

One concern is that ministers and their mandarins simply don't understand science and that if they are given an inch they will take a mile.

There might be pressure to cut funding for the search of obscure sub-atomic particles, for example in order to spend more on materials science which might have a greater benefit to the economy.

Sir Paul believes that the research community will be able to stand up for itself.

He is clear that he wants the seven research councils to remain as they are - but argues their relative budgets should be reviewed periodically.

"What I am proposing strengthens the research base. To have a more joined-up research strategy.

"So instead of seven individual research strategies we have a combined voice and a proper platform for a strategy.

"I think a good interaction between politicians and scientists is not only good for the scientific endeavour but society."

The elephant in the room is next week's spending review.

Science funding has been relatively protected by George Osborne.

It has been frozen and ring-fenced since 2010 by a Chancellor who has become increasingly amenable to research. He has become convinced that it can be a useful tool for his plans to increase UK productivity.

In order to maintain or possibly improve on the deal they struck five years ago the scientific community will have to give George Osborne something back.

And a little more meddling by the Chancellor may be a price they may well be prepared to pay for a good settlement in the Comprehensive Spending Review.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external

- Published19 November 2015

- Published13 January 2015

- Published14 November 2014