Will coal be on the dole after COP21?

- Published

- comments

Many countries still rely on coal-fired power

For coal, COP21 is meant to be the start of the long goodbye.

This is the conference that's supposed to consign the black stuff to the ash heap of history.

The world will finally tilt definitively towards windmills and a future filled with sunbeams and smiles.

Perhaps not.

Coal has certainly been on the back foot.

A recent report from the International Energy Agency, external showed that in 2014 renewables accounted for half of the world's new power generation capacity and they have already become the second-largest source of electricity after coal.

The UK, the home of the coal-fired industrial revolution, recently announced that power generation from unabated coal would end within 10 years.

"Let me be clear: this is not the future," said Energy Secretary Amber Rudd.

Well, it's not the future, unless you live in India or a host of other emerging economies around the world.

Global energy demand is growing rapidly, and according to the IEA is expected to increase by a third by 2040, with the main demand coming from China, India, Africa, the Middle East and South East Asia.

Look at India - the world's third largest economy but only accounts for 6% of global energy use. Some 240 million people still lack access to electricity.

The country is determined to address this, and they are going on a coal binge to do it.

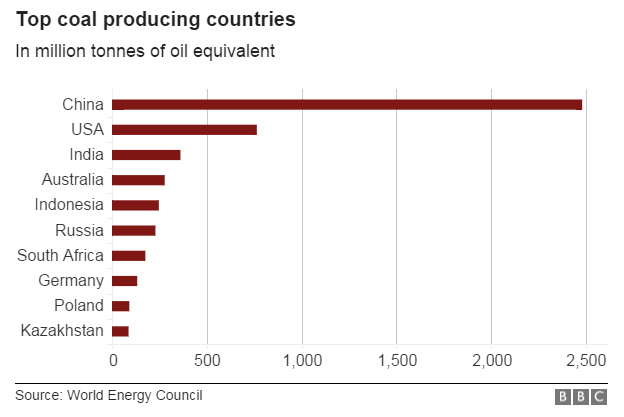

By 2020, India will be the world's second largest producer of coal, overtaking the US. And it will be the world's largest importer.

They are not alone. As my colleague David Shukman has been reporting, the Philippines is set to establish 23 new coal fired plants by 2020.

In fact 40% of the 400 gigawatts of generation capacity to be added in Southeast Asia by 2040 will be coal-fired.

And while coal use will decline in the developed economies of the EU and the US, the whiff of sulphur will be rising in Japan, where coal's share of the energy mix by 2030 will increase to 30%.

According to Benjamin Sporton from the World Coal Association, a bit more honesty about coal's role in the future is needed at COP21.

"I think that we need to recognise that there is a role for coal going forward," he told me.

"Many countries are using coal and are going to use it for decades to come so we ought to be talking about how the outcome of Paris can support countries to use the best coal technology. And ultimately we need to be talking about carbon capture and storage (CCS) as well."

No easy task

Others take a different line.

Hydroelectricity is a major source of renewable power

Tim Gore from Oxfam acknowledges that it won't be easy to wean emerging economies away from cheap coal. For the many developing countries that have not yet built electricity grids, leapfrogging to renewables makes a lot more sense.

But if COP21 is serious about lightening the lignite, significant amounts of cash will have to be found to fund the move towards greener sources.

"I think it's right that developing countries are clear just how big a transformation is required to move away from fossil fuels," he said.

"This is not a light undertaking. I think that sometimes the issue of a global transformation is presented as inevitable, but actually from most developing country perspectives it doesn't look like that."

In Paris you will have rich countries who are moving away from carbon rich fuel, telling the rest of the world who are moving towards coal, that they must stop doing that by an agreed date in the future.

"It's problematic for us to make that commitment at this point in time. It's certainly a stumbling block," Ajay Mathur, a senior member of India's negotiating team told news agencies this week.

"The entire prosperity of the world has been built on cheap energy. And suddenly we are being forced into higher cost energy. That's grossly unfair," he said.

How will negotiators square this circle?

If an agreement in Paris pushes greater investment into renewables, the costs will fall further and that may encourage developing governments to go greener quicker. If fossil fuel subsidies are tackled this will also help, and an effective price or tax on carbon would certainly speed up the deployment of solar and wind.

Technology's vital role

The coal lobby argues that a critical component must be CCS technology.

However industry and governments alike are waiting on the other to put up the cash and drive through the technology.

In the UK this week the Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) declared that it will fully remove the £1bn available for a pioneering Carbon Capture and Storage competition scheme for power stations.

Carbon capture and storage:

Carbon capture technology is being perfected around the world

Carbon capture and storage is a way to prevent carbon dioxide building up in the atmosphere.

It is a rapidly evolving technology that involves separating carbon dioxide from waste gases produced in electricity generation and industrial processes.

The carbon dioxide is then stored underground, for example in old oil or gas fields such as those found under the North Sea.

There is a feeling that the reluctance to invest in the CCS might spring from a fear that if industry spends hundreds of millions on proving it works, they may not recoup that investment.

The big markets are likely to be in China and India. And both countries will want this technology, essentially for free, as part of a global deal.

There is the potential in all this for compromises - but it is very complicated and may be beyond the scope of this year's conference.

But Paris could give a clear signal that this process has to start - and fast!

Meanwhile many environmentalists are very wary of linking our ability to limit carbon to what they believe is an unproven, expensive, big boy's toy!

"We need to be a bit careful about thinking that CCS is a magic bullet," said Tim Gore.

"It's a nice fairy tale, to make ourselves feel a bit better."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.