Europe's ExoMars missions are go - finally

- Published

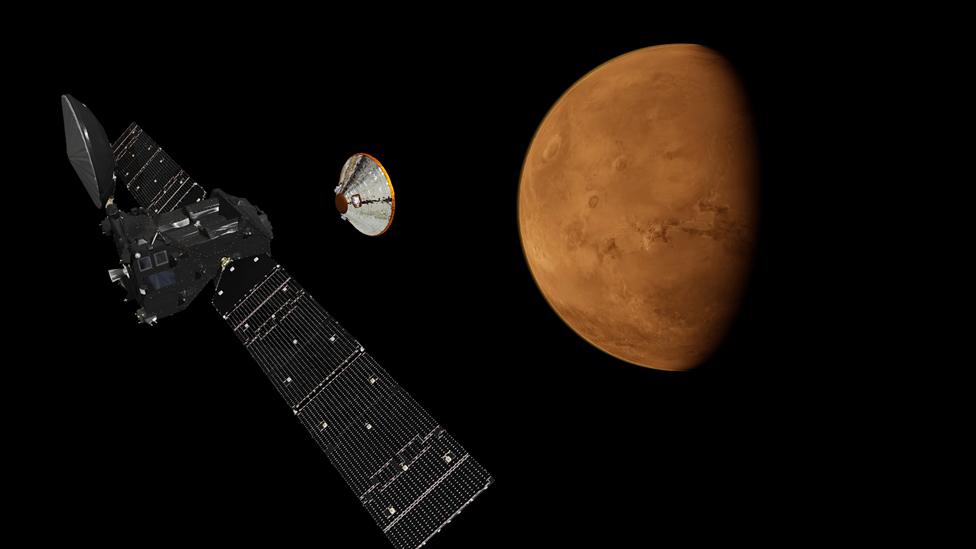

Artist's impression: The satellite will release the lander three days out from Mars

The first of Europe's ExoMars missions is finally ready to get under way.

This initial venture will involve a satellite going to the Red Planet to study trace gases, such as methane, in the atmosphere.

The orbiter will also drop a probe on to the surface to test technologies needed to land the second mission - a rover - that should arrive in 2019.

The path to this point has been a tortuous one, with the programme coming close to collapse on several occasions.

ExoMars has gone through several iterations since being approved formally by European Space Agency (Esa) member states in 2005. Its vision has expanded from a small technology demonstration to a two-legged endeavour that will cost in the region of 1.3 billion euros.

In all the upheaval, ExoMars has also now become a joint undertaking with the Russian space agency (Roscosmos).

The new partner literally rescued the project when the Americans dropped it as a priority, and will be providing key components and science instruments for both missions, as well as the Proton rockets to get all the hardware to Mars.

Wednesday saw officials from both Esa and Roscosmos inspect the finished satellite and test lander at Thales Alenia Space in Cannes, France. TAS is the lead European contractor for ExoMars.

One of its senior directors, Vincenzo Georgio, said that it had taken a herculean effort to get the satellite and demo lander ready for flight.

"The baby's there in the cleanroom and ready to go," he told me.

"How did we get here? Two reasons. The first was the willingness of the people who wanted this programme. And the second was that, despite all the storms - the funding problems, the politics - we worked as if nothing was happening outside. We worked triple shifts; we worked seven days a week. And you see the result."

Vincenzo Georgio: "The schedule for the ExoMars rover is challenging"

The 3.7-tonne Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) is equipped with remote sensing experiments that will make a detailed inventory of Mars' atmospheric gases.

A key quest is to better understand the presence of methane. From previous measurements, its concentration is seen to be low and sporadic in nature. But the mere fact that it is detected at all is really fascinating.

The simple organic molecule should be destroyed easily in the harsh Martian environment, so its persistence - and those occasional spikes in the signal - indicate a replenishing source of the gas.

The explanation could be geological: a simple by-product perhaps from water interactions with particular rock minerals at depth. There is, though, the tantalising prospect that the origin is biological.

Most of the methane in Earth's atmosphere comes from living organisms, and it is not a ludicrous suggestion that microbes might also be driving emissions on Mars.

"We are very interested in (a) trying to confirm the presence of methane and (b) also being able, maybe, to explain the origin," explained Esa ExoMars project scientist Jorge Vago.

"And either way, whether the origin is geological or biological - if the methane is coming from the sub-surface it requires the presence of liquid water, and that points to a Mars that is more 'alive' than we have thought up to now."

Jorge Vago: "TGO has two ways of looking for methane"

Schiaparelli is the entry, descent and landing demonstrator. It is named after the 19th Century Italian astronomer Giovani Schiaparelli, who used his telescope to describe surface features on the Red Planet.

He famously mapped what he called "canali" or channels, which others would later confusingly (perhaps lost in translation) refer to as canals.

The 600kg Schiaparelli probe will attempt the hazardous task of putting down safely on Mars' Meridiani plain.

Some of the systems it uses in the process of entry, descent and landing - notably its radar, computers and their algorithms - will find employment again in the Russian-built mechanism that puts the ExoMars rover on the planet in 2019.

The University of Bern's Nic Thomas explains how TGO's camera, CaSSIS, will work

Even if it works, Schiaparelli will be a short-lived affair.

It will have battery power to run a few environmental sensors and transmit their data home, but that is all. There will not even be an "I'm on Mars" photo because it carries no surface camera.

It is hard to believe today that any probe would go to the surface of another planetary body without this capability, and its omission on Schiaparelli is a decision senior Esa officials say they now regret.

All that said, the TGO will have a spectacular stereo camera aboard, which its principal investigator, Nic Thomas, hopes will provide a steady stream of imagery for the public to enjoy.

"The public can get engaged in this stuff very, very quickly, and it's nice to be able to feed that," he said. "Our target is to try to get images out into the public domain in three months after they've been acquired."

The TGO satellite, Schiaparelli and all their support gear head to the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan in mid-December.

Roscosmos is making the Proton ready for launch on 14 March. Arrival at Mars occurs in mid-October.

All up, the launch mass of the fuelled satellite and the lander is 4.3 tonnes

Schiaparelli itself will not operate for long - perhaps only a few days on the surface of Mars