COP21: Drone to monitor rubbish dump gases

- Published

- comments

Unwanted food produces 21 million tonnes of greenhouse gas in the UK every year

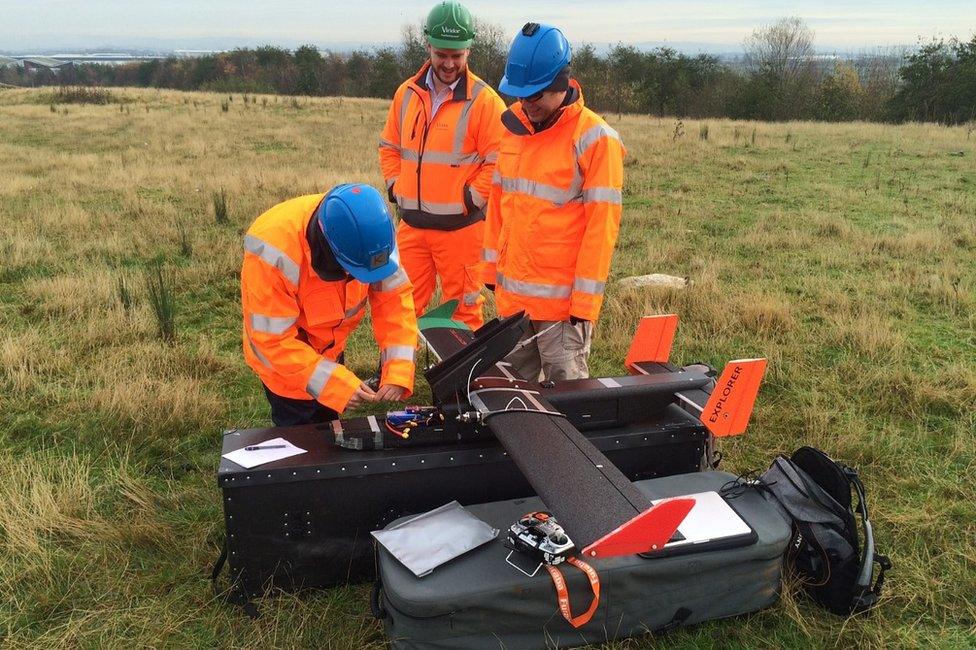

An experimental drone fitted with sensors is being deployed to monitor gases rising from rubbish dumps.

The unmanned aircraft is being flown above Britain's 200 landfill sites to study a major source of UK emissions.

The latest estimate is that unwanted food produces 21 million tonnes of greenhouse gas in the UK every year.

Although the number of landfill sites is being reduced, the emissions from decomposing matter are set to last for decades.

The drone project is being run by the University of Manchester and the Environment Agency (EA).

According to Doug Wilson, the EA's Director of Scientific & Evidence Services, the research is driven by the need to find an easy way to monitor a long-term problem.

"It'll allow us to get a better understanding of the emissions from a particular site.

"There are 830,000 tonnes of methane from the waste sector and methane is 25 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide,"

"The more we can understand how to reduce those emissions, the more useful and positive it will be."

One of the venues for the first test flights is a landfill site at Pilsworth near Manchester which has been closed and is now awaiting restoration by its operators Viridor.

Some of the methane emitted from the site is collected and then piped to a small power station nearby - but an unknown amount rises into the atmosphere.

The drones should enable a better understanding of the emissions from a particular site

I watched as the drone's gas monitoring sensor was checked before the aircraft was launched by catapult for a 20-minute flight around the boundaries of the site.

Dr Peter Hollingworth of the University of Manchester said that the concept had been proved with data successfully gathered about carbon dioxide emissions and calculations made to understand the methane levels too.

"Ideally what we're getting to is an autonomous flight - and you'd come out to a site with a smaller aircraft than this one, or with two or three of them, and fly them at different points on the site and measure the incoming flow and the outgoing flow.

"A team could then - in a day or so - quantify exactly what that site is emitting."

This project comes amid a growing awareness of the financial and carbon cost of food waste - with a major campaign led by the chef Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall.

Liz Goodwin of the recycling charity WRAP says that the emissions from old food mean there is a tangible connection between everyday life for a typical household and the negotiations on curbing greenhouse gases at the UN summit in Paris starting next week.

"I find it very shocking," she told me.

"Not only is it costing the average family with children £60 a month but the 4.2 million tonnes of food that could have been eaten, a lot of it ends up in landfill where it basically just rots and gives off greenhouse gas emissions."

One statistic produced by WRAP's researchers is that the equivalent of 86 million chickens is thrown away in the UK every year - either as whole birds or parts of poultry.

WRAP estimates that the waste chicken alone contributes about 690,000 of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases a year - assuming the carbon costs of the raising, feeding and transporting the birds are included, as well as the release of gases if they are dumped in landfill.

That total is roughly the same as the emissions from 290,000 cars per year.

Chicken

To understand more about food's role in emissions, we asked researchers to examine what happens during the decomposition of a fresh chicken.

At the Biomolecular Sciences Research Centre at Sheffield Hallam University, Dr Jillian Newton kept a chicken under heat lamps for the course of a week.

Our timelapse camera captured the sight of the bird darkening and then going through a period of rapid swelling as gases formed and expanded inside the chicken.

Dr Newton calculated that the 1.2kg chicken produced 31.2 litres of biogas - which would contain 79.8g of methane and carbon dioxide.

"When food is thrown away and discarded it goes through different states of decomposition," she said.

"Every piece of organic food that we throw away will essentially produce methane - some pieces of food may take longer, some may produce gas more quickly.

"And, depending on where it's been thrown, if it's somewhere where a lot of bacteria can get to it, it'll produce methane quicker."

To help reduce emissions - and to turn waste into a useful resource - a growing proportion is diverted from landfill into projects that generate electricity.

The waste firm Viridor runs two different types of plant that use waste to power turbines - anaerobic digesters that trap methane and incinerators that use waste as a source of fuel.

Dan Cooke of Virodor said: "Any food waste - whether it's leftover food or food that's gone off - it's important that people put that in the right bin.

"We can take that material and squeeze the energy out of it so that people, by recycling their food waste, are actually helping keep the lights on."

Many landfill sites are due to close but, even when they do, they will leave a legacy: gases will continue to seep out of them for decades to come.

Follow David on Twitter, external.