COP21: Beginner's guide to the UN Paris climate summit

- Published

The Paris conference is seen as the best opportunity in six years to agree a new global climate treaty

What is the climate conference for?

In short, the world's governments have already committed to curbing human activities such as burning fossil fuels that release the gases that interfere with the climate.

But that isn't problem solved.

The difficulty comes when you try to get 195 countries to agree on how to deal with the issue of climate change. Every year since 1992 the Conference of the Parties (COP) has taken place with negotiators trying to put together a practical plan of action.

This year's COP21 in Paris is the last chance for this process. Negotiators agreed in 2011 that a deal had to be done by the end of 2015.

Critics would say the problem of climate change mustn't be that urgent if it takes 20 years to agree on a solution.

But defenders argue that it's taking such a long time because decisions are taken by consensus, meaning nothing is agreed until everything is agreed. The parties believe that despite this huge limitation, it is the best way of guaranteeing fairness. We all share the planet, they say, so all should have an equal say in what happens to it.

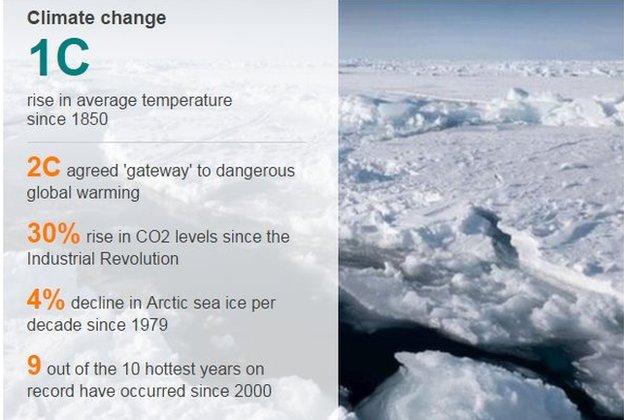

Climate change

1C

rise in average temperature since 1850

-

2C agreed 'gateway' to dangerous global warming

-

30% rise in CO2 levels since the Industrial Revolution

-

4% decline in Arctic sea ice per decade since 1979

-

9 out of the 10 hottest years on record have occurred since 2000

Why does it have an odd name?

COP21 is short for the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

That long winded title was created in Rio in 1992 where countries concerned about the impacts of climate change came together under the United Nations to do something about it.

They signed a convention that came into force in 1994 and has now been ratified by 195 countries, including the United States.

The key aim is the "stabilisation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system".

Who is attending?

Around 40,000 people from all over the world are participating in the two weeks of talking in one form or another.

There are huge numbers of government delegates, mainly civil servants. These groupings range in size from two-person teams to those of several hundred in the case of wealthier nations.

There are a lot of lobbyists and representatives from business, industry and agriculture. And representatives from environmental groups from all walks of life.

Political leaders are in Paris for just one day, to make speeches and encourage their negotiators towards an effective compromise. And their environment ministers will be there too, at the end of the talks, to try to shape a final deal.

What are they hoping to achieve?

Think of everything in the world around you. The phone or laptop on which you are viewing this article, the food you might be eating, the clothes you are wearing. Almost everything you see, touch, feel or eat has been grown, built, powered or transported by energy that comes from fossil fuels.

They've been brilliant for the world - enabling us to industrialise, develop, take hundreds of millions out of poverty. But the carbon dioxide created when we use these materials is having a well documented "greenhouse effect", trapping heat on the surface of the planet.

When the earth warms about 2°C above pre-industrial times, scientists say there will be dangerous and unpredictable impacts on our climate system. And we're already half way to that danger point,

So the purpose of Paris is to work out a way of limiting emissions of greenhouse gases, while allowing countries to continue to grow their economies, and providing assistance to the least developed and those most affected by rising temperatures.

Simple?

It's probably the most ambitious international co-operative ideal ever proposed.

What are the key disagreements?

The final destination is a world where temperatures rise not much more than 2°C above the level they were in 1850-1899 period. That's the long term aspiration countries have already agreed to. But there are big splits between countries on how to get there. Developing countries say they want the right to use fossil fuels, such as oil, coal and gas, to help take their people out of poverty. Rich nations have had unrestricted use of these for 200 years, now it is their turn, they argue. So the Paris deal needs to find a way of balancing the need to cut these gases with the right to use them.

The question of who will pay is critical.

Who is going to fork out for the transition to renewable energy, such as solar and wind power, for countries that can't afford it? Who is going to pay to help poor countries adapt to rising sea levels and more intense droughts and heatwaves? Can countries which suffer future impacts of rising temperatures sue the richer countries for emitting gases in the past that might have caused these problems? These are all tricky, contentious and divisive issues.

One of the big underlying questions though is fairness. The richer countries say the world has changed since the UNFCCC started back in 1992. Back then the world was divided into developed and developing nations on the basis of income. But the divide is no longer so distinct and the richer nations want a greater number of emerging economies to shoulder the rising costs of climate change in future.

Will any of this make a difference?

Potentially a huge difference.

In the 1980s scientists discovered a hole in the ozone layer, and international agreement among all the countries of the world, called the Montreal Protocol, set out a way of tackling the problem. Quite quickly the world stopped using the destructive gases that caused the trouble and today the hole is healing.

Tackling climate change requires similar methods but on a much larger scale.

An ambitious deal in Paris will limit the use of greenhouse gases and put the world on the pathway to lessening the impacts of climate change. But the reality of politics and negotiation means we will probably get a fudgy compromise that will achieve some of that.

The belief will be that over time, negotiators will strengthen the deal and ambition will increase.

This is not a forlorn hope. Look how far humans can come, simply by iterating and re-iterating an idea until we make it better. I give you smart phones and the internet as examples of this approach.

So despite the potential for failure and the likelihood of a messy compromise, one outcome of the Paris conference, weak or strong, is that sustainability will be at the heart of everything we attempt to do in the future.

And that would be one of the greatest human achievements.

UN climate conference 30 Nov - 11 Dec 2015

COP 21 - the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties - will see more than 190 nations gather in Paris to discuss a possible new global agreement on climate change, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the threat of dangerous warming due to human activities.

Explained: What is climate change?

In video: Why does the Paris conference matter?

Analysis: Latest from BBC environment correspondent Matt McGrath

More:, external BBC News special report (or follow "UN Climate Change Conference" tag in the BBC News app)