How chemists plan to sniff out bombs

- Published

The explosive used in the Paris attacks was relatively easy to make

The suicide bombers in the Paris attacks used an explosive that is relatively easy to synthesise at home.

Chemists, however, are leading an effort to develop sensors to sniff it out.

The explosive, called triacetone triperoxide (TATP), is produced by combining chemicals sold in pharmacies and hardware stores.

Several research groups across the globe are now developing sensors to detect TATP before it can be detonated.

"Anyone who could follow a recipe to make a pumpkin pie could follow the recipe to make TATP," says Dr Kenneth Suslick, professor of chemistry at the University of Illinois.

That is why terrorists find the chemical so attractive, say experts. Suicide bombers all over the world have used TATP, from Palestinians in the West Bank to the "shoe bomber" Richard Reid.

Sensitive sensors

Chemists are seeking to exploit a physical characteristic of TATP known as vapour pressure. This property refers to how readily a compound converts from the solid to the gaseous state.

Because TATP has a relatively high vapour pressure, it easily becomes a gas. Therefore, in theory, a suicide bomber wearing a vest containing TATP should emit enough gaseous particles to set off the alarm on a sensor.

Dr Suslick's group has developed a handheld scanner that detects TATP and other explosives after they react with a colorimetric sensor array. His work is funded by the US Department of Defense.

When gaseous TATP molecules enter the sensor, they encounter a solid acid catalyst. The acid converts TATP back into its constituent parts, acetone and hydrogen peroxide.

Hydrogen peroxide, an unstable oxidising agent, then reacts with dye molecules in the sensor, causing them to change colour.

By detecting these colour changes, the highly sensitive portable scanner can detect fewer than two parts per billion TATP.

Furthermore, in a recent paper published in the journal Chemical Science, Dr Suslick's team describes a more advanced sensor their team has created, which uses a panoply of various color-changing chemical indicators.

This new sensor detects about a dozen different explosives.

Dr Otto Gregory, professor of chemical engineering at the University of Rhode Island, believes that Dr Suslick has developed a good technology. That has not prevented his lab, however, from working on its own.

A different approach

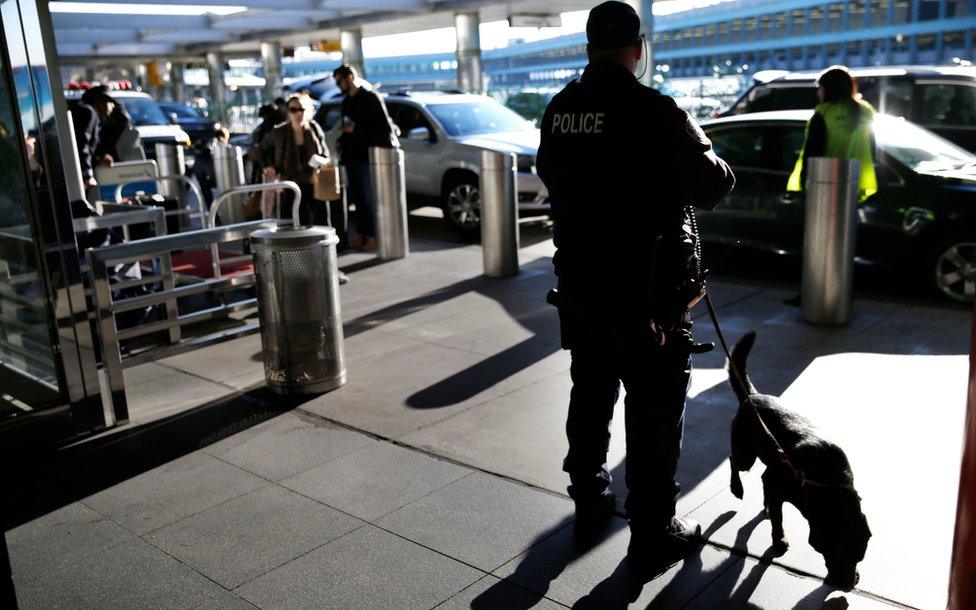

Sniffer dogs are an alternative, but have disadvantages

Funded by the US Department of Homeland Security, Dr Gregory's team has published a paper in the journal ECS Transactions that describes an entirely different strategy for detecting TATP.

Their sensor employs a tin oxide catalyst. When TATP interacts with the catalyst, it produces heat that is detected by the sensor.

Though dogs can be trained to find TATP, chemical sensors will probably be more reliable.

"The problem with dogs is two-fold," Dr Suslick says. "First, they want to please their handler and so they have a tendency to give a positive response if things get boring, just for the attention.

"Second, their attention can wander, just like you or me, and the problem is that you don't know when they've drifted off to thinking about the neighbouring cat or that foxy Doberman down the block."