COP21: Carbon emissions 'to stall or even decline' this year

- Published

The burning of coal for power is a large contributor to atmospheric levels of greenhouse gases

Global emissions of carbon dioxide are likely to stall and even decline slightly this year, new data suggests.

Researchers say it is the first time this has happened while the global economy has continued to grow.

The fall-off is due to reduced coal use in China, as well as faster uptake of renewables, the scientists involved in the assessment add.

But they expect the stall to be temporary and for emissions to grow again as emerging economies develop.

According to the study, external, published in the journal Nature Climate Change and presented here at COP21 in Paris, emissions of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels and industry are likely to have fallen 0.6% in 2015.

They increased by around the same amount in 2014.

Since 2000, global emissions have grown annually by 2-3%. The slowdown has occurred while the global economy has grown by 3% in both 2014 and 2015.

"We're expecting a stalling in emissions, possibly even a little decrease," said Prof Corinne Le Quere from the University of East Anglia, UK, who led the data analysis.

"The main cause is from decreased coal use in China. It's restructuring its economy, but there is also a contribution from the very fast growth in renewable energy worldwide, and this is the most interesting part: can we actually grow renewable energy enough to offset the coal use elsewhere?"

No peaking

China continued to be the world leader in emissions, according to the report, responsible for 27% of the global total. With its economy slowing, coal use has declined just as concerns have grown over air pollution issues in urban areas. There has also been a rapid take-up in renewables.

However, Prof Le Quere said that despite this year's figures, the global peak of emissions use was not yet in sight.

"As the emerging economies are mostly based on coal, as they grow we are expecting a restart in the emissions," she told BBC News.

"And in the industrial economies like in the UK, where emissions are going down, the decrease is relatively modest, mostly 1-2%. We would be looking for a much faster decrease than that to offset the growth in the developing countries."

The UN secretary general seems to see the funny side of things at the opening of the ministerial section at COP21

India was the fourth largest emitter overall in in 2014, with its emissions now matching those of China's in 1990.

India's growth in 2014 was offset by a similar decline in the European Union, which experienced an unusually warm winter combined with a sustained long-term decline in carbon output.

But the rapid growth in Indian emissions is causing some concern for researchers.

"The learning curve took China about 20 years to achieve this current level of efficiency," said Prof Dabo Guan, also from the University of East Anglia.

"If everything moves to India without significant energy structure improvements then emissions will significantly grow. We have already seen the Indian emissions take off in the last couple of years."

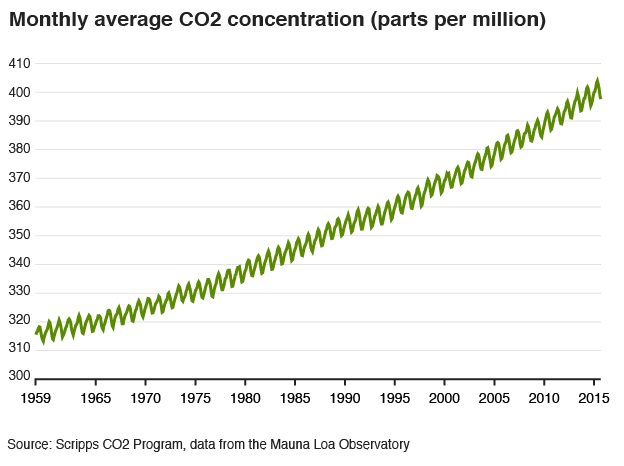

Annual emissions add to the concentration of CO2 already in the atmosphere, which continues to rise

The study has been published in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The scientists involved believe that while the slowdown in emissions is welcome, albeit temporary, it could be a snapshot of the future if a deal can be done here in Paris.

Prof Le Quere told the BBC: "To deal with climate change we need emissions to go to zero - and we are now talking about zero growth and not zero emissions - so we are still a long, long way from that."

"It could begin to look like a peak in emissions after Paris if the agreement is very strong."

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc., external

UN climate conference 30 Nov - 11 Dec 2015

COP 21 - the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties - will see more than 190 nations gather in Paris to discuss a possible new global agreement on climate change, aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the threat of dangerous warming due to human activities.

Explained: What is climate change?

In video: Why does the Paris conference matter?

Analysis: Latest from BBC environment correspondent Matt McGrath

In graphics: Climate change in six charts

More: BBC News climate change special report