Fog history of Atacama reconstructed

- Published

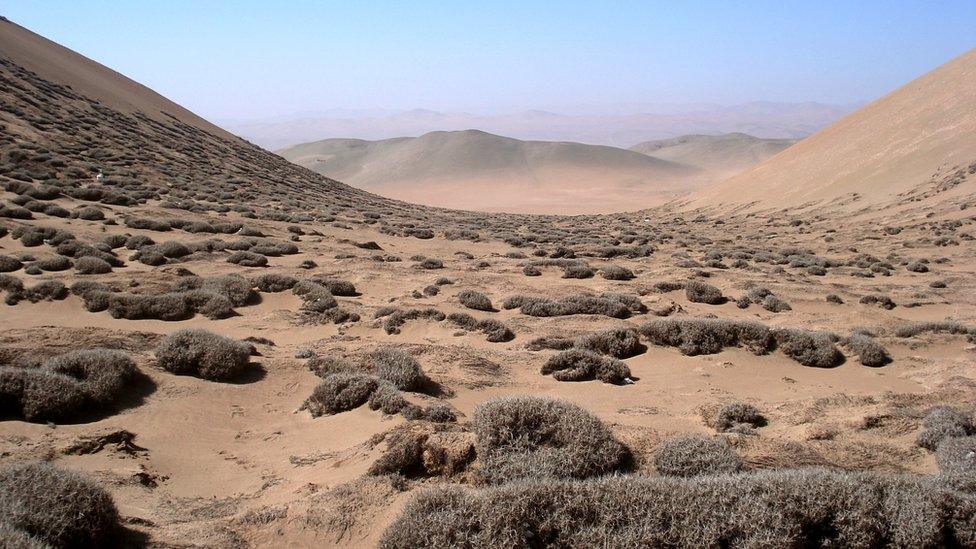

The plants, pictured here by co-worker Angélica Gonzalez, underpin a whole ecosystem

It is hard to imagine you could reconstruct a record of fog dating back thousands of years, but this is exactly what Chilean scientists have done.

The low-lying cloud is seemingly so transient and intangible, and unlike rivers and glaciers it leaves no easy-to-read impressions on the landscape.

And yet, a Santiago team has been able to trace the fog history of the Atacama Desert by studying Tillandsia plants.

Their chemistry suggests strongly that this local fog has increased over time.

It is a period covering the last 3,500 years.

"I don't think there's any other place in the world where I've actually seen a record of fog, even spanning the last hundred years," said Claudio Latorre Hidalgo from the Catholic University of Chile.

"What little we know about fog is from measurement instrumental data that we have, and from satellite data that only spans the last 20 years.

"So, this is actually a unique opportunity to study the evolution of a fog ecosystem over the Late Holocene, and what are the major drivers and controls of the mechanisms that produce that fog in the long term - the very long term."

The palaeoclimate expert was discussing his team's research here at the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union - the world's largest annual gathering of Earth scientists.

Claudio Latorre Hidalgo: "The fog is the plants’ only source of water and nutrients"

The Atacama is famous for its super-arid conditions; there are places where it has not rained for years.

But life can eke out an existence if it can exploit the fog that rolls in off the Pacific. Tillandsia are a perfectly adapted opportunist.

These wiry, grey plants have no roots. They clutch weakly at sand dunes, but arrange themselves at every spatial scale to maximise their capture of the fog.

They derive everything they need from the damp air - not simply the must-have water, but also all the chemical nutrients required to underpin their biology.

Dr Latorre Hidalgo and colleagues have dug deep into the dunes to uncover a multi-millennia succession of Tillandsia; and they have described a pronounced trend: the younger the plants, the more of the lighter type, or isotope, of nitrogen atom that they have incorporated into their tissues.

The structure of Tillandsia maximises fog capture – by growing in a mesh (Top-R) and using appendages on the leaves called trichomes (Bottom-R) to corral the water

Analysis of modern fog suggests this lighter nitrogen is favoured, and so the observed trend in the Tillandsia would strongly indicate the fogs of the Atacama have increased over time… with some complications.

"How the nitrogen gets into the fog is a much more complex question," said Dr Latorre Hidalgo.

"I suspect a lot of that nitrogen is of marine origin. There is a huge oxygen-minimum zone off the coast of northern Chile, where there is a lot of denitrification going on.

"So, there is a lot of molecular nitrogen going into the air and a lot of nitrous oxide as well.

"We know there is both ammonia and nitrate in the fog. So, you get both organic and inorganic forms of nitrogen."

Oxygen-minimum zones are mid-water regions in the ocean that are extremely low in oxygen abundance, in part because marine organisms are removing it very fast and also because the waters that move into the zone fail to replenish the oxygen as they themselves are depleted. This is usually cold, upwelling water. And, again, this fits the overall picture because cold coastal waters will produce more fog.

"Our monthly fog collector data shows there is a significant trend with the coastal sea-surface temperatures and the fog. So, when you get El Niño events (and local surface waters warm), this warm water dissipates the thermal inversion that's holding in the low-lying cloud and this dissipates the fog.

"We think that over the last three thousand years, the coastal waters have gotten much colder, much more productive and that's releasing nitrogen from this oxygen-minimum zone to fertilise the plants."

And it is more than just the Tillandsia that are benefiting.

The plants' success in trapping and using fog anchors a whole ecosystem that supports creatures as diverse as beetles, scorpions, spiders and even lizards.

The team has dug down through the dunes to find and analyse the ancient plants

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external