Diamond squeeze hints at metallic hydrogen

- Published

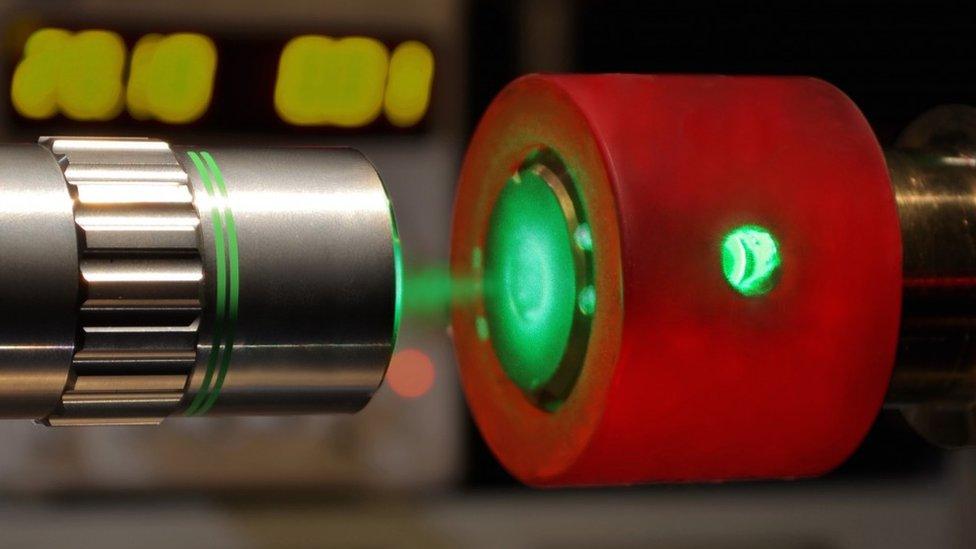

The team probes the properties of its hydrogen in the diamond anvil cell

British researchers think they have come close to creating a long-sought new state for hydrogen.

They have put a sample of the familiar gas under so much pressure that it takes on a previously unseen solid crystalline form.

The team tells the journal Nature, external that this phase may be just a step away from so-called metallic hydrogen.

Predicted 80 years ago, this exotic substance could lead to ultra-fast computers and even super rocket fuel.

"We think we've reached a state of the material that is probably the precursor to metallic hydrogen," explained Ross Howie, formerly at Edinburgh University but now based in China.

"If you compare what we've observed experimentally with what's theoretically predicted for metallic hydrogen - they're very strong similarities between the two," he told the BBC's Science In Action programme.

The group used a set-up called a diamond anvil cell to compress its sample of molecular hydrogen.

This apparatus is essentially two gems that have been placed in opposition to each other.

Their polished tips, comparable in size to the width of a human hair, are made to press into a cavity containing the sample.

"The volume of hydrogen we use is about a micron cubed - a size that is on the order of a red blood cell," said the Nature paper's lead author, Philip Dalladay-Simpson, from Edinburgh's Centre for Science at Extreme Conditions, external.

"We use brute force - a large lever arm. We apply about a tonne of force on the back of the diamonds to generate huge pressures inside the cell."

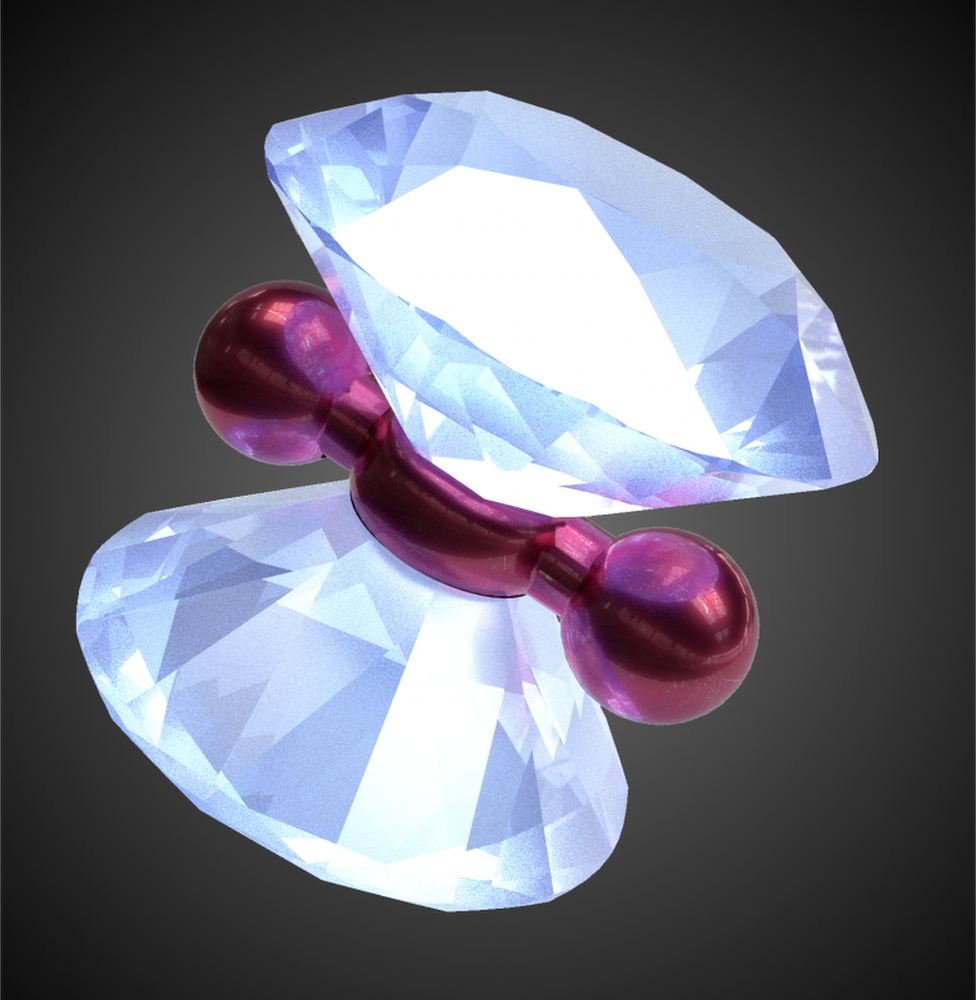

An artist's impression of a hydrogen molecule under compression in a diamond anvil device

In their experiments, the scientists are able to achieve in excess of 350 gigapascals (3.5 million atmospheres) at room temperature. These pressures are not dissimilar to what would be experienced at the centre of the Earth.

The big squeeze on the molecules of hydrogen gas turns them first into a liquid and then into a solid.

As the pressure gets ever more intense, the atoms in the hydrogen molecules pack closer and closer together, and the electrical conductivity in the crystalline material increases.

Ultimately, the hydrogen atoms should stack so efficiently that their electrons become shared - just as in a metal.

However, the team does not quite see this phase, but rather something that is probably just short of it.

"This would be a mixed structure of different layers, where you might get a layer of hydrogen molecules followed by an atomic layer, and these alternate," said Dr Howie, who is now affiliated to the Center for High Pressure Science & Technology Advanced Research, external in Beijing.

The work puts new constraints on where the full metallic hydrogen phase might exist: possibly below 450 gigapascals at room temperature.

The ambient temperature is very significant, because if metallic hydrogen can ultimately be produced this way it opens the door potentially to a new type of perfect (zero resistance) conductor - a material to boost the performance of next-generation computers.

"It's been predicted that metallic hydrogen could be a room-temperature superconductor, which is still yet to be achieved with any material," said Dr Howie.

"However, because we are playing with such small quantities, the practical applications at this stage are not clear."

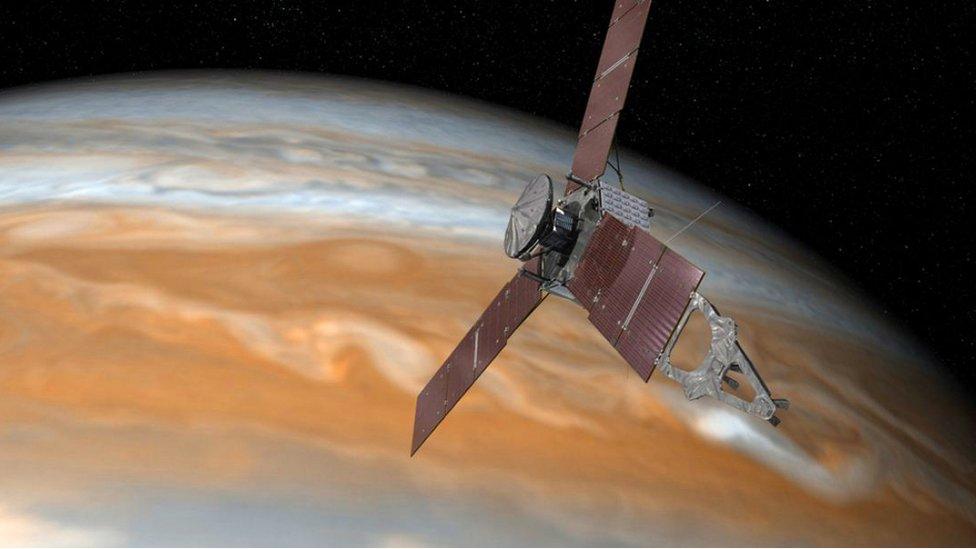

The Juno spacecraft will investigate the interior of Jupiter, starting later this year

Another prediction for metallic hydrogen suggests it could form the basis of a super fuel, producing substantially more thrust than the standard super-chilled hydrogen used in today's rockets.

Scientists are also fascinated by metallic hydrogen because they think it may account for a large fraction of the internal composition of planets such as Jupiter.

The high pressures and temperatures that exist several thousand kilometres below the gas giant's cloud surface are believed to produce a fluid form of metallic hydrogen. Movement in this electrically conducting liquid is very likely the source of the world's colossal magnetic field.

Nasa has a probe called Juno arriving at the planet later this year to investigate the possibility.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external