Global fishing catch significantly under-reported, says study

- Published

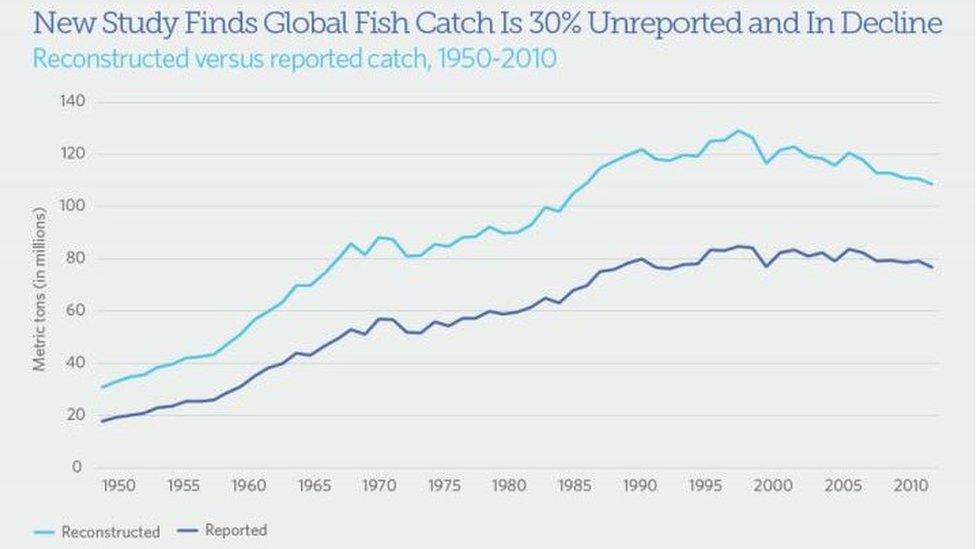

Global fish take based on official figures underestimates the actual catch size according to this study

The amount of fish taken from the world's oceans over the last 60 years has been underestimated by more than 50%, according to a new study.

Researchers say that official estimates are missing crucial data on small scale fisheries, illegal fishing and discarded by-catch.

The authors argue that global fishing catches are now declining rapidly because stocks have been exhausted.

But other researchers have questioned the reliability of the new study.

The UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) is the body that collates global statistics on fishing from countries all over the world.

According to their official figures, the amount of fish caught has increased steadily since 1950 and peaked at 86 million tonnes in 1996 before declining slightly to around 77 million tonnes in 2010.

But researchers from the University of British Columbia argue that the official figures drastically under-report the true scale of fishing.

They argue that the figures submitted to the FAO are mainly from large scale "industrial" fishing activities and do not include small scale commercial fisheries, subsistence fisheries as well as the discarded by-catch and estimates for illegal fishing.

The scientists say their "catch reconstruction" method give a far more accurate picture of the scale of the impacts of fishing around the world.

They say that reconstructed catches, that include estimates and data on the under-reported activities, show that the world took 53% more fish from the seas than the official figures indicate.

They argue that around 32 million tonnes of fish go unreported every year - more than the weight of the entire US population.

"The catches are all underestimated," said lead author Prof Daniel Pauly.

"The FAO doesn't have a mandate to correct the data that they get - and the countries have the bad habit of reporting only what they see - if they don't have people who report on a given fishery then nothing is reported. The result of this is a systematic underestimation of the catch and this can be very high, 200-300% especially in small island states, in the developed world it can be 20-30%."

Prof Pauly gave the Bahamas as an example where there was no reporting of fish caught by small scale fishers. But when the researchers dug a little deeper and went to the big hotels and resorts, they found invoices from small scale fishermen who sold their catch directly.

Not only have more fish been taken from the seas than have been reported say the authors, but the decline in fish caught since the mid 1990s has been far greater than the official figures show.

A graph showing the differences between the official figures and the reconstructed catch

The researchers say this isn't because the world is doing less fishing, it's because over exploitation means there are simply less fish being caught.

"It was never really sustainable," said Prof Pauly.

"We went through one stock after the other, for example around the British Isles, the stocks in the North Sea were diminished right after the Second World War.

"And then British trawlers went to Iceland and did the same thing there, and so on and so did the Germans, the Americans, so did the Soviets.

"They had to expand to survive and now the fisheries are in Antarctica."

The unwanted bycatch is often dumped back into the ocean and not counted in official figures

While other scientists in this field have praised the comprehensive nature of the study, some have criticised the methods used.

"I think we all agree that global catches are probably higher than reported but I do not think that this new catch reconstruction is sufficiently reliable to draw conclusions concerning trends in catches or global fisheries," said Dr Keith Brander, an expert of on fisheries and marine ecosystems who is now an emeritus scientist at the Technical University of Denmark.

"It may point to particular regions and fisheries sectors that require substantial improvement in statistics in order to improve fisheries management, but to do this one really needs to get into the fine detail," he told BBC News.

The authors say that they have every confidence in their work. They say they are not based on a handful of studies but on around 200 research papers conducted over a decade by a network of 400 scientists based all over the world.

While praising the "huge and impressive amount of work" that went into the study, Prof Trevor Branch from the University of Washington said that the report raises another important question that still remains unanswered.

"Catches only tell us what we take out, not what the status of the remaining fish is," he said.

"So it's like trying to measure deforestation from counts of trucks of lumber driving away from forests."

The study has been published, external in the journal, Nature Communications.

Follow Matt on Twitter., external