UK floods: Drone provides researchers with unique data

- Published

Images captured by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) offer a landscape-wide view of flooded river systems

Images from an unmanned aerial vehicle suggest excessive management of floodplains limit their ability to hold water and slow the flow of floodwater.

Drainage channels on floodplains meant water was returned to rivers too quickly, exacerbating flooding further downstream, researchers observed.

They added a drone allowed them to gather a unique view of the impact of the floods that hit northern England.

The University of Salford team were able to survey 60km in one day.

"Because we have the UAV we can access areas really quickly and the height we can fly at, you don't have to get very close to the river because you can fly it 500 metres away from you where you can get the images," explained Neil Entwistle from the university's School of Environment and Life Sciences.

"What we basically did in Storm Desmond was to try and get to as much of the River Eden's catchment (area) that we could in order to see where the flood extent was, and capture evidence of it and get data on floodplain inundation."

Before researchers were able to use UAVs, the alternative was to use a helicopter which was prohibitively expensive.

Using the drone with a camera, Dr Entwistle was able to collect hundreds of images of the Eden's catchment area over a 60km stretch - almost half of the 145km-long river - in less than a day.

Shortly before the Eden flows into the sea, it passes through Carlisle and was responsible for much of the flooding recorded in the Cumbrian city during December.

Recently released data by the Centre for Hydrology and Ecology, external showed that the Eden experienced record flow rates, resulting from record levels of rain falling on already saturated soil.

Dr Entwistle said one of the aims was to capture images showing "trash lines" that indicated the outer reaches of the flood water.

"We were looking for evidence of floodplain use and floodplain inundation, and getting evidence from as much of the catchment area as we could in order to see if there were any areas that were not inundated with water but should have been, according to the Environment Agency's flood map, external," he told BBC News,

Dr Entwistle's colleague, George Heritage, added: "Our suspicions were that maybe it was not all being used and this was causing a problem for Carlisle.

"As it turned out, from the data we collected, everything was being used. This has real implication for these extreme events and controlling those extreme events in the catchment because if there is no spare capacity, where do we find that capacity in the future?"

Dr Heritage voiced concern over the current debate of whether or not dredging would help ease the risk of flooding. He said that each river catchment system was unique and there was no one-size-fits-all solution but warned such a strategy would not be appropriate for the River Eden.

"If we do improve the drainage on the floodplains through dredging the ditches and dredging the stream that feed the major rivers, then we will increase the speed that the water gets into the main channel, which in turn will increase the peak of the flood and we will have a higher peak in Carlisle as a result - that's a definite."

He added that the lack of resistance on the floodplains meant that water was still flowing at a "fairly fast speed", resulting in a large volume of water reaching Carlisle quickly and overtopping the city's flood defences.

"If we manage those floodplains in a different way, particularly by roughening them up - patches that are not farmed grassland - but are given over to developing scrub landscapes and more natural floodplain vegetation then they will act as buffers to slow the flood down," he told BBC News.

"It's a recommendation we can make quite confidently from the data that has come from the drone surveys."

By allowing floodplains to regenerate naturally and allowing natural vegetation to become established - such as scrub and wet woodlands - the sites will also provide a buffer, slowing the flow of the floodwater and capturing some of the larger objects being carried in the floodwater, like tree trunks.

Without these natural buffers, the objects are carried downstream until they reach an obstruction such as a road bridge across the river. The combination of being battered by floodwater and foreign bodies resulted in numerous bridges being damaged or destroyed.

The aerial images also revealed the characteristics of the flood along the River Eden as well as showing how quickly the water had drained from the floodplains

In another study carried out during the recent series of winter storms, Dr Entwistle focused his attention on an area of interest along the River Irwell, near the town of Rawtenstall, Lancashire.

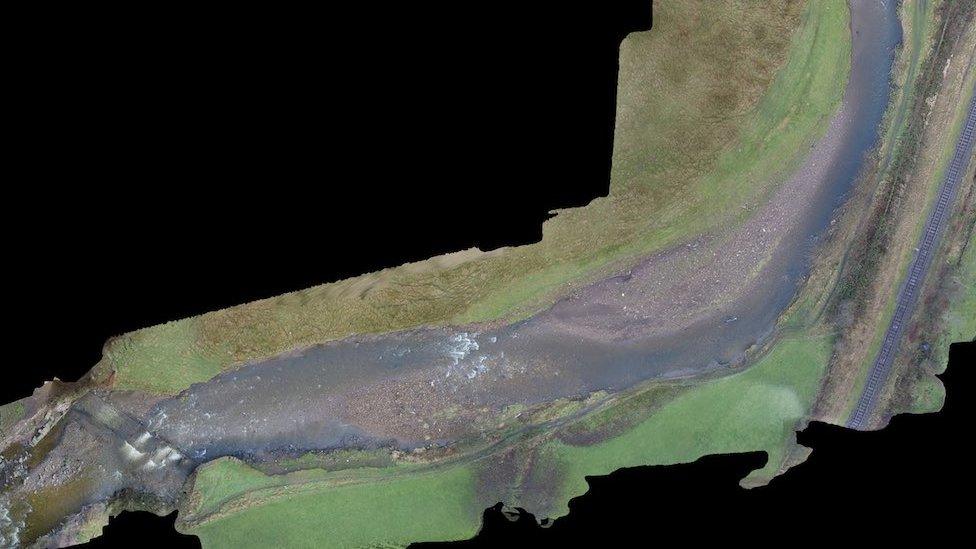

"In Rawstenstall, because it was a smaller area and the result of a structural failure (collapsed weir), we were overlaying hundreds of photographs in order to get a really high resolution image in order to create a 3D model of erosion and deposition, allowing us to quantify the levels of change over time," he said.

The researchers deployed their UAV shortly before the arrival of Storm Desmond, giving them a high-definition reference composite image of the site.

They returned to repeat the exercise once Storm Desmond had passed, and then again following Storm Frank over the Christmas period, which hit the Irwell catchment area quite badly.

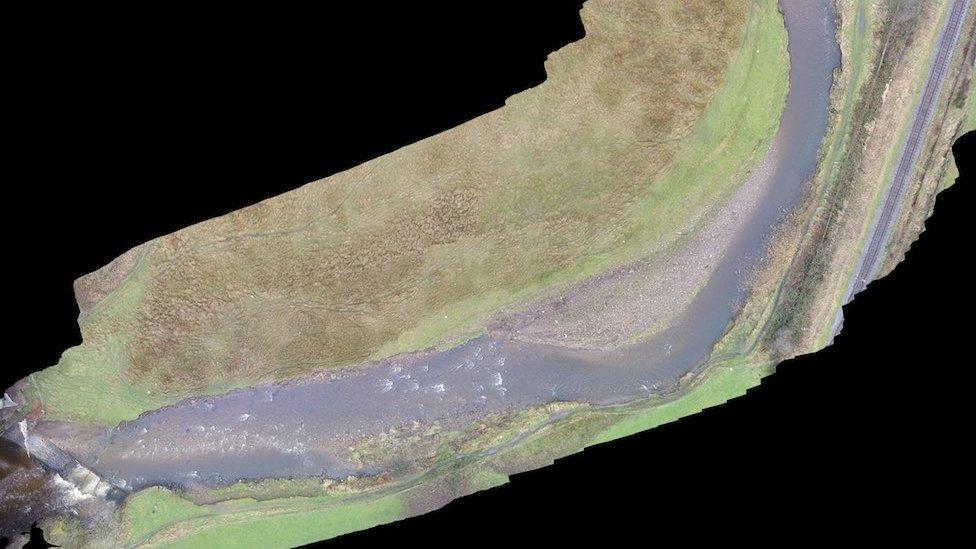

River Irwell, 4 December 2015: A collapsed structure (a weir - bottom left of the image) on the River Irwell near the town of Rawtenstall, Lancashire, gave the researchers a chance to monitor and model the changes to erosion and deposition along this stretch

River Irwell, 18 December 2015: Following Storm Desmond, the team returned to collect a new set of images of the river that revealed a widening of the river in front of the damaged weir

River Irwell, 6 January 2016: The impact of flooding during Storm Frank was much more dramatic, with the Pennine Way footpath running alongside the river being washed away, and considerable damage to a high embankment that offered protection to the East Lancs railway line (right-hand side of image). The river had also visibly widened.

What is natural flood management?

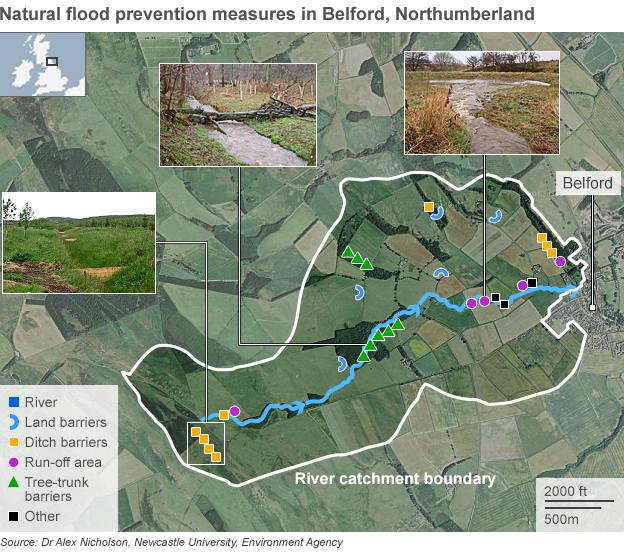

Natural flood management schemes rely on a combination of small-scale interventions with the aim of reducing the speed of the flow of converging water before it reaches larger rivers.

Features include small barriers in ditches and fields, or notches cut into embankments, all of which divert the water into open land.

Felled trees can also be laid across streams in wooded areas and help push unusually high waters into surrounding woodlands, although such schemes need very careful planning and management.

- Published16 January 2016

- Published7 December 2015

- Published7 January 2016