Reconstructing the 'world's biggest dinosaur'

- Published

A cast of the titanosaur skeleton has been installed in the American Museum of Natural History

"Seeing the reaction of the people is fantastic. It all makes sense - we do this because we're interested in the science, but it all goes back to society."

Palaeontologist Diego Pol is talking about a very special fossil specimen, a giant dinosaur he excavated in the desert of central Argentina. This titan of the Cretaceous Period, or at least a fibreglass replica of its skeleton, has now taken up residence as an exhibit in New York's American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).

The cast is 122ft long (37.5m) and represents a giant plant-eating titanosaur that lived in the forests of Patagonia between 100 and 95 million years ago. It may well be the biggest dinosaur yet discovered, but is so new it doesn't yet have a formal scientific name.

The dinosaur cast was unveiled before a packed crowd of media on 14 January. The skeleton grazes the 19ft-high (5.8m) ceilings of the museum's Wallach Orientation Center and its head and neck stick out of the room, gazing towards the lifts.

The story behind the exhibit is told in a new BBC One documentary presented by Sir David Attenborough.

For Sir David, who is well known for presenting series about the living world, the domain of fossil creatures represents something of a return to his roots.

"My original love was fossils, and they were easier to find than much of the wildlife in Leicestershire. The fossils there weren't dinosaurs; there were marine deposits there," Sir David told me.

Sir David Attenborough: "Nature doesn't produce more than it needs so if it could carry [a certain weight] it almost certainly did"

"You'd get fish skeletons as well as lovely ammonites and belemnites. I think fossils are some of the most romantic things. And I studied palaeontology at Cambridge.

"I don't see how you can fail to be excited by dinosaurs. One of my theses about why kids are so excited is that you know a lot about dinosaurs, but you don't know everything about dinosaurs - there's room to speculate."

Asked how the titanosaur compared with the famous Dippy specimen in London's Natural History Museum, Sir David replied: "It's one-and-a-half times bigger than Dippy in length... it's substantially bigger."

The story behind this monster dino specimen goes back to 2013, when a shepherd spotted the tip of a huge fossilised bone sticking out of a rock in La Flecha Farm in the desert of Central Patagonia.

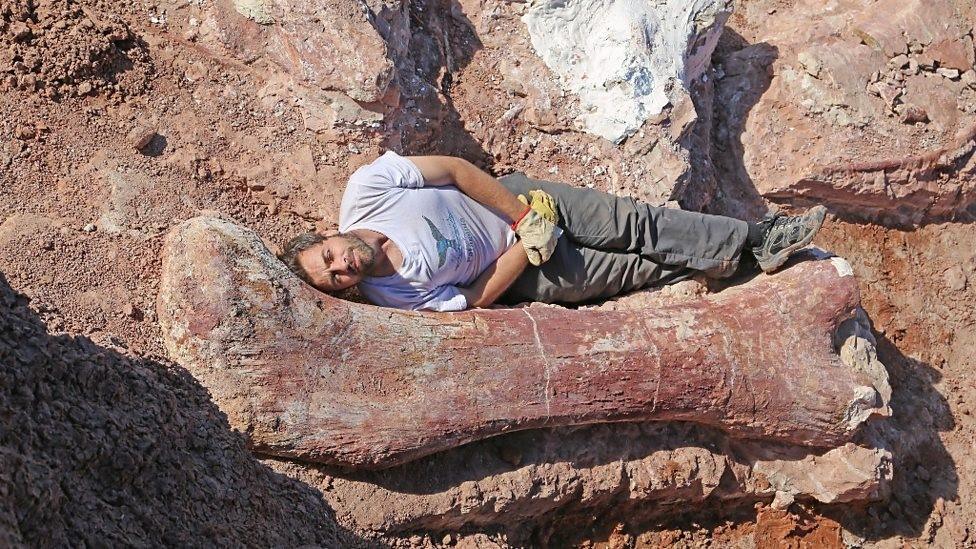

Palaeontologists from the Egidio Feruglio Paleontology Museum (MEF) in Trelew set up camp at the site and proceeded to excavate the bone. It turned out to be a 2.4m-long femur - the largest of its type ever found.

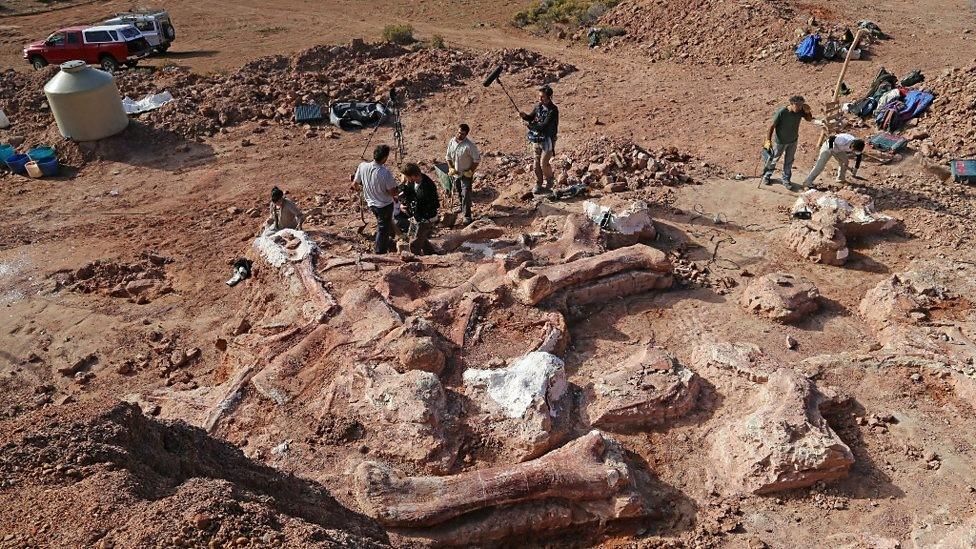

By the end of the dig they had uncovered 223 bones belonging to seven specimens.

The example represented in New York appears to be the biggest of this batch, and bigger than its closest rival - another giant titanosaur called Argentinasaurus. But it's difficult to say for sure, because Argentinasaurus is much less complete, and its size has to be estimated from just a few bones.

"It's really unique to have so many bones from these large dinosaurs," says Diego Pol.

Dr Diego Pol lies next to a titanosaur femur

The latest discoveries come from sedimentary rocks deposited in a riverine environment 100 million years ago.

"You have the floodplains, where many animals were. Some of them, when they died, were buried by these flooding events from the river and that's how the fossilisation process starts," Diego Pol told BBC News.

"In the case of the titanosaur, we didn't find evidence of a big flood [as the cause of death]. So our hypothesis is that these animals were near the water and just happened to die at this spot."

Sir David points out that "we're still in the very early stages of the science. There's still an awful lot we don't know". But while it will take time to resolve the picture, the questions posed by the discoveries so far are fascinating.

A key one is how these Cretaceous herbivores grew to be so massive.

"This is one of the big questions. There are many things that were different in the Cretaceous. The climate was warmer than it is today, the ecosystems were composed of different plants and animals," says Dr Pol.

"What is special about this particular time in the Cretaceous? You only find these gigantic dinosaurs between 100 million and 80 million years ago."

The TV crew was able to film this reconstruction of the Titanosaur

Crucial to solving this conundrum is reconstructing the ecological context in which the titanosaurs lived. Dr Pol and his colleagues have found rich plant remains in the Patagonian fossil beds, as well as the remains of other dinosaurs.

Sir David explains: "We don't know [why they grew so big], it's entirely speculation. But the basic logic is that if you have food that needs a lot of digestion - a lot of the vegetation around at that time was extremely fibrous - then you need to keep it in your stomach for a long time. Then you need a very big stomach and very big apparatus to carry it."

In addition, he says: "One of the defences that elephants have is that they're very big and it's hard for predators to bring them down. There can be an arms race where the predator gets very big and the prey gets bigger still."

Diego Pol adds: "An adult animal this big had no predators, that's for sure. Not even the largest carnivorous dinosaurs would have dared to attack one of these.

"But the juveniles were probably subject to predation. We know for instance that titanosaurs formed nesting grounds [elsewhere in Patagonia], where hundreds of dinosaurs got together during the reproductive season. That's a classic strategy to protect the young."

The researchers have found numerous teeth of carnivorous dinosaurs from the La Flecha Farm site. Many belong to carcharadontosaurs - so-called shark-toothed dinosaurs - which were a Southern Hemisphere response to Tyrannosaurus rex.

The excavation site is located near Trelew, Central Argentina

The titanosaurs appear to have been a fleeting evolutionary experiment, testing biological limits on extreme size. And it's impossible to know which of the specific conditions that favoured such massive beasts would later change, hastening their extinction (if that is indeed the way it happened).

Whatever, such scenarios bring to mind present-day species which, having evolved in a particular ecological context, are now under threat as humans transform the environment around them.

I asked Sir David how far we should go to preserve those species that are at most risk of disappearing from our planet.

"With any species you choose, there's a whole cluster of answers to that question. What do you do, for example, with the Giant Panda? You could argue that the Giant Panda relies on eating large amounts of bamboo, but the bamboo forests are getting smaller and smaller. It's also highly specialised," he says.

"But on the other hand, it's part of the natural world which we're a part of. This isn't sentiment that I talk about; it's a whole suite of things: of curiosity, of affection, of perspective on evolutionary creation. And I would think that humanity was simply neglecting its inheritance if it simply allowed it to go.

Sir David adds: "The problem about ecosystems is that they are highly complex - they're like pieces of clockwork. You can take a cog out of the clock and it may still tell the time. But you don't know - it might stop immediately. You certainly don't know the long-term effects when you interfere with an ecosystem."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external

Attenborough And The Giant Dinosaur will broadcast on BBC One on Sunday 24 January at 6.30pm.