Case made for 'ninth planet'

- Published

Why do the Caltech astronomers think there may be a ninth planet?

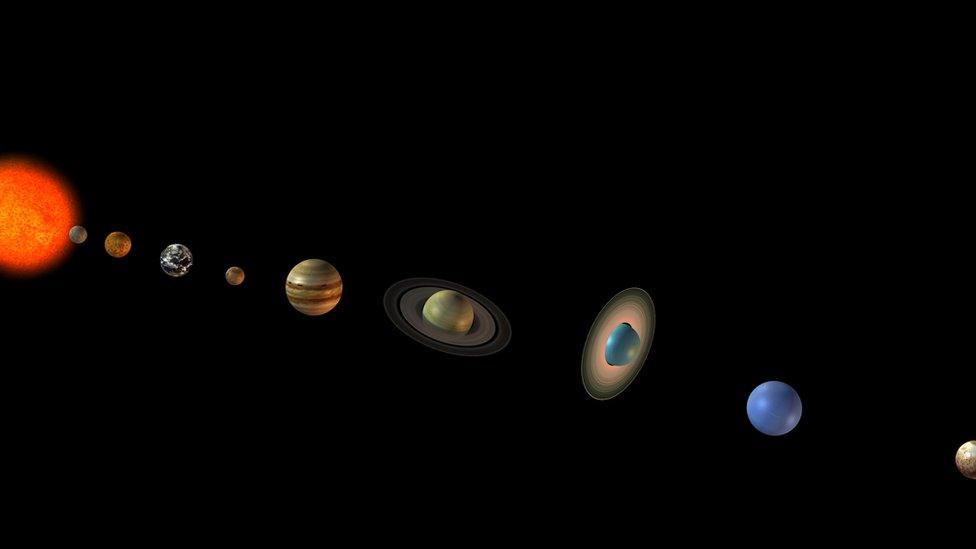

American astronomers say they have strong evidence that there is a ninth planet in our Solar System orbiting far beyond even the dwarf world Pluto.

The team, from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), has no direct observations to confirm its presence just yet.

Rather, the scientists make the claim based on the way other far-flung objects are seen to move.

But if proven, the putative planet would have 10 times the mass of Earth.

The Caltech astronomers have a vague idea where it ought to be on the sky, and their work is sure to fire a campaign to try to track it down.

"There are many telescopes on the Earth that actually have a chance of being able to find it," said Dr Mike Brown.

"And I'm really hoping that as we announce this, people start a worldwide search to go find this ninth planet."

Strange swing

The group's calculations suggest the object orbits 20 times farther from the Sun on average than does the eighth - and currently outermost - planet, Neptune, which moves about 4.5 billion km from our star.

Dr Ellen Stofan, Nasa's chief scientist, is "a bit sceptical" about the existence of a ninth planet

But unlike the near-circular paths traced by the main planets, this novel object would be in a highly elliptical trajectory, taking between 10,000 and 20,000 years to complete one full lap around the Sun.

The Caltech group has analysed the movements of objects in a band of far-off icy material known as the Kuiper Belt. It is in this band that Pluto resides.

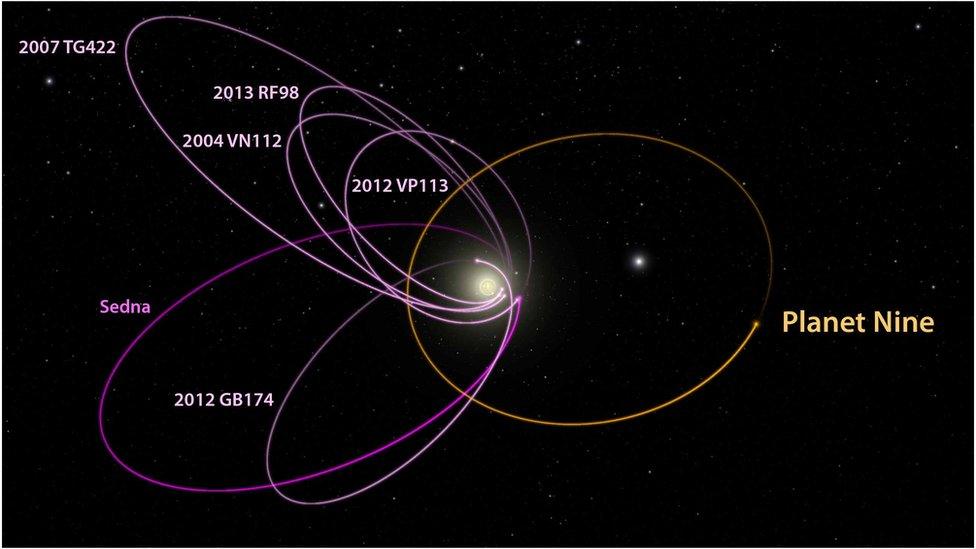

The scientists say they see distinct alignments among some members of the Kuiper Belt - and in particular two of its larger members known as Sedna and 2012 VP113. These alignments, they argue, are best explained by the existence of a hitherto unidentified large planet.

"The most distant objects all swing out in one direction in a very strange way that shouldn't happen, and we realised the only way we could get them to swing in one direction is if there is a massive planet, also very distant in the Solar System, keeping them in place while they all go around the Sun," explained Dr Brown.

"I went from trying very hard to be sceptical that what we were talking about was true, to suddenly thinking, 'this might actually be true'."

The 'ninth planet' - where to look?

The six most distant known objects in the Solar System with orbits exclusively beyond Neptune (magenta) all line up in a single direction. Why? Drs Brown and Batygin argue that this is because a massive planet (orange) is anti-aligned with these objects. Can telescopes now find this planet? Could the evidence already be in observational data but no-one has yet recognised it? The hunt is on.

The idea that there might be a so-called Planet X moving in the distant reaches of the Solar System has been debated for more than a hundred years. It has fallen in and out of vogue.

What makes this claim a little more interesting is Dr Brown himself.

He specialises in finding far-flung objects, and it was his discovery of 2,236km-wide Eris in the Kuiper Belt in 2005 that led famously to the demotion of Pluto from full planet status a year later (Dr Brown's Twitter handle is @PlutoKiller, external).

At that stage, Pluto was thought to be slightly smaller than Eris, but is now known to be just a little bit bigger.

Others who model the outer Solar System have been saying for some years that the distribution of sizes seen in the objects so far identified in the Kuiper Belt suggests another planet perhaps the size of Earth or Mars could be a possibility. But there is sure to be strong scepticism until a confirmed observation is made.

Nasa's chief scientist, Ellen Stofan, said she certainly needed telescopic evidence.

"The intriguing point is: we've identified lots of planets (beyond our Solar System) in this category of 'super-Earth' with our Kepler telescope; over 5,000 planet candidates. The fact that we don't have a planet in that size class between Earth and Neptune makes us think, 'well, maybe we are missing one', and maybe they've predicted it," she told BBC News.

Dr Brown and Dr Konstantin Batygin (@kbatygin, external) report their work in The Astronomical Journal, external.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published21 January 2016