Venus flytrap 'counts' to control digestion

- Published

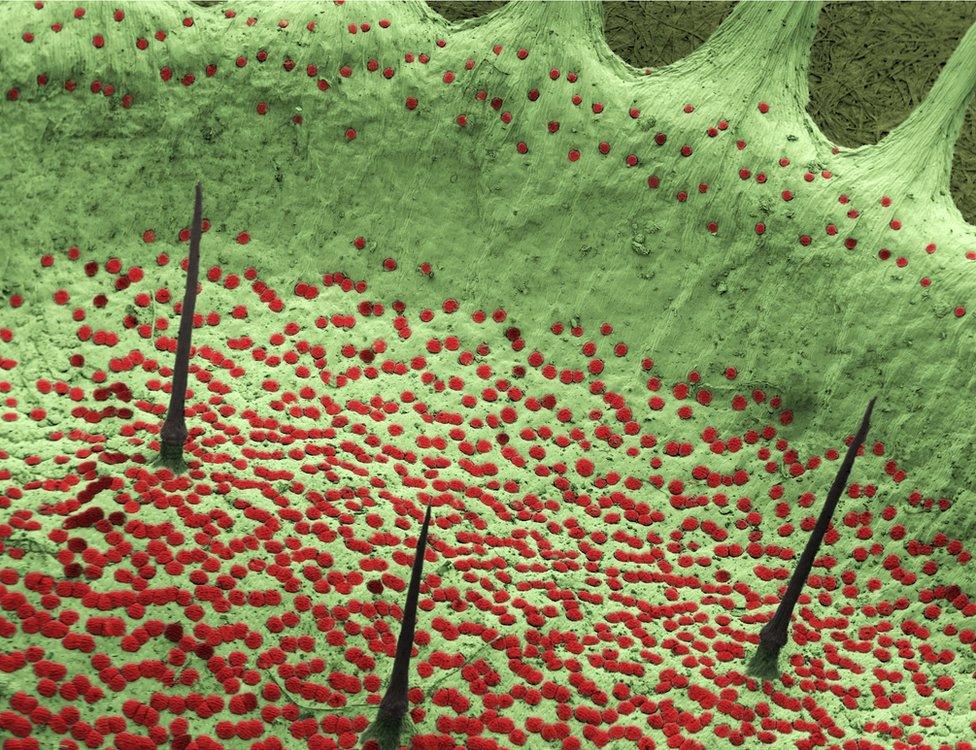

Don't move a muscle: Five touches of the trigger hairs bring on digestive juices

Venus flytraps "count" the number of times a struggling insect touches their trigger hairs and use that information to ramp up their digestion, according to a study by German scientists.

They recorded the impulses generated by these hairs, on the inside of the plant's maw, and measured various changes within the plant.

For example, two touches trigger a hormone increase; five bring on the production of digestive enzymes.

The work appears in Current Biology, external.

Previous research had already shown that it takes two touches of the trigger hairs, within a 15-20 second time window, to cause the trap to shut. This saves the plant from wasting energy snapping at raindrops or other false alarms.

Sucking up sodium

The new study reveals how the flytrap responds to subsequent touches, ramping up its digestive processes once a catch is confirmed and boosting them further if the kill seems to be a big one.

"The number of action potentials informs [the plant] about the size and nutrient content of the struggling prey," said senior author Rainer Hedrich, from the University of Würzburg.

"This allows the Venus flytrap to balance the cost and benefit of hunting."

Prof Hedrich and his colleagues stimulated the trigger hairs up to 60 times, using a special instrument or, in some cases, an unfortunate cricket.

Several hairs, pictured here using an electron microscope, are present on each side of the trap

As those numbers climbed, as well as seeing rises in hormones and "hydrolases" for breaking down the meal, the team saw a gradual spike in the production of a sodium channel.

This piece of cellular machinery, they believe, helps the flytrap to drink up sodium ions from the dissolving animal, via special glands.

Rebecca Hilgenhof, a botanical horticulturalist who looks after carnivorous plants for Kew Gardens in London, said the findings were fascinating.

"For me, the interesting thing is that there needs to be something that tells the plant... to do certain things [after] a certain amount of touching, and a certain amount of time."

It will be interesting to explore that control mechanism further, she said, and to find out how a series of electrical impulses from the trigger hairs produce the different stages of the plant's response.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published5 October 2015

- Published23 June 2013

- Published5 August 2011

- Published8 April 2011