Fears grow amid Brazil's Zika crisis

- Published

- comments

The Brazilian authorities are targeting mosquito breeding sites

An alarming mixture of confusion and fear is blighting the pregnancies of thousands of women across this teeming tropical city in the northeast of Brazil, and wherever else the Zika virus has infected people.

Every day the emergency clinic at one of Recife's largest hospitals sees queues of nervous women so long that they reach into the car park, and the medical staff, already stretched, are now overwhelmed.

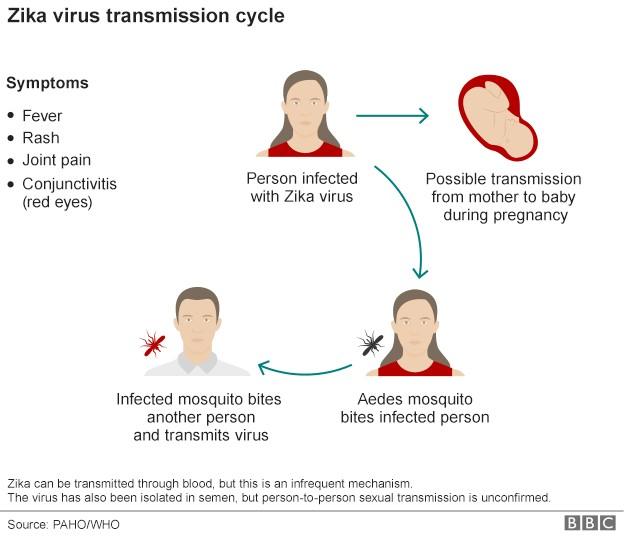

The enemy is uncertainty because the symptoms of Zika infection are worryingly vague: aches, a rash, itching and conjunctivitis are all typical and the slightest sign of them naturally leads the women to rush for help.

One woman, close to her due date, told me that to avoid being bitten she now never goes out at night and keeps herself covered in mosquito repellent. Another sat slumped and sobbing as she said tests had confirmed that she is carrying the virus.

In the hot, crowded waiting room, with an action movie playing loudly on a television, a series of anguished cries suddenly grabbed everyone's attention.

A young woman, four months pregnant, had just been told that she may be infected and the impact of the news proved too much for her.

The red eyes of Sara Ferreira da Silva were all too obvious. Seven months pregnant, she thinks that she may have picked up an infection, though is not sure if it might be Dengue, a major threat here, or Zika.

"At the moment today I'm feeling worried because I have the symptoms," she said. "I have pain in my body, headache, I had fever, 38-39 degrees, and some red spots appeared on my belly."

But establishing if there is Zika infection is not easy. The virus is only active for about a week and hunting for a legacy of it in antibodies does not always produce a definitive result.

Often the first firm indication of trouble is when an ultrasound scan is carried out sometime around 22-24 weeks into the pregnancy, and this is an agonising moment because research into Zika is too incomplete to provide firm answers.

Dr Adrianna Scavuzzi, who is in charge of maternal health at the public medical centre IMIP, said: "When you see the ultrasound is with something wrong you have to tell her and then you know that after you tell her she will ask you many questions - if the the children will walk, will hear properly, will see properly and we don't know

So medical specialists are working seven days a week to investigate the virus and to try to understand its impacts.

Damage to the nervous system might also be a complication - with limbs that cannot be controlled

Although there is no categoric proof that the virus is stunting the growth of the babies' brains, that is regarded as highly likely by those on the frontline of this health crisis.

One assumption is that greater damage is done earlier in pregnancy when the brain would normally grow most rapidly - but this is not confirmed and is urgently being researched.

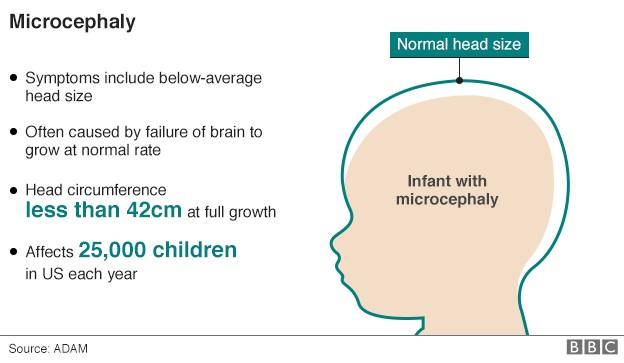

Another worrying unknown is a scenario of extreme disability where babies are born not only with microcephaly, the condition of the small brain, but also with damage to the nervous system with the result that the limbs cannot be controlled.

This is known as arthrogryposis, and pictures of babies born with it show distorted arms and legs, and X-rays reveal a lack of connection in the joints. The babies can only survive in intensive care.

Dr Vanessa Van der Linden and colleagues, who are preparing a paper on the condition, say six cases have now emerged in Recife and that it is "highly probable" that Zika is to blame.

She said: "The problem with these babies is in the spine. The motor neurones that makes the muscle move have a problem so these babies have some muscles without function."

While the research effort races to catch up with the crisis on the ground, the city authorities here are stepping up efforts to stamp out the mosquitoes that carry the virus.

Streets and alleyways in the favelas are regularly sprayed with insecticide, although when I watched one operation it seemed quite haphazard, only reaching the fronts of people's homes and none of the rooftops or yards.

And the crucial search for the mosquito larvae has been hampered until now by the inability of officials to enter homes without permission - I saw one pair of soldiers turned away and an abandoned dwelling left alone.

So, from today, officials will have the right to break in if needed - a sign of the escalation in measures needed to get a grip on the outbreak.

That might help to turn the tide of the crisis here.

The talk is of a war against the virus and, at the moment, it is not going well enough either to limit the number of cases or to reassure all the pregnant women reaching for their bellies, and wondering.

And for women thinking of pregnancy, there is a warning from one young mother.

Micaela da Souza's daughter Anica Vitoria has severe microcephaly and needs to be continually rocked to prevent her from becoming agitated, and her advice reflects the uncertainties of the science.

"I'd say it's not the moment to get pregnant because so far nobody knows where does this virus come from, how can this happen?"