Gravitational waves: Reward for five decades of teamwork

- Published

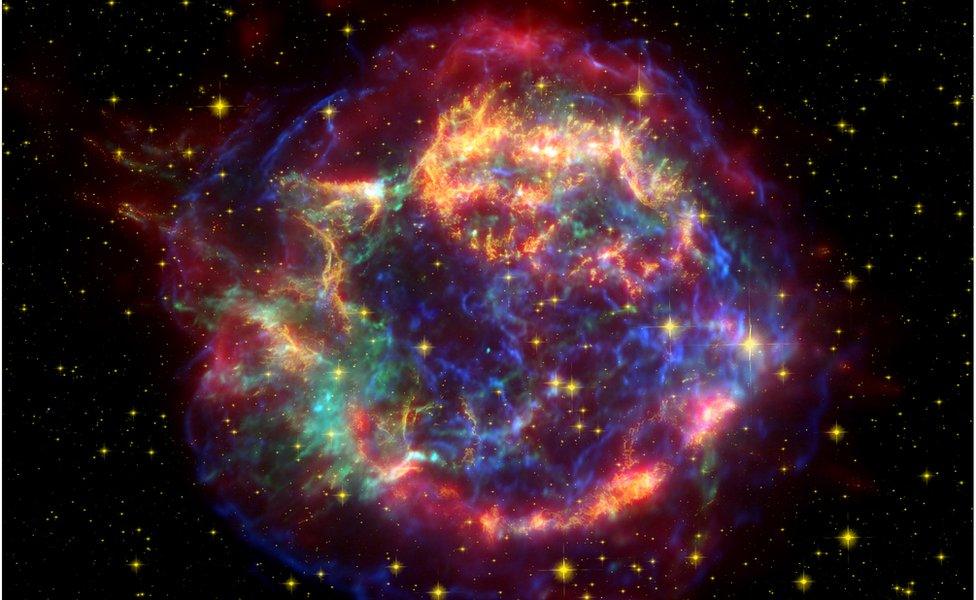

Science now has a whole new way to study the Universe

An international team of scientists has made the first-ever direct detection of gravitational waves.

This historic discovery not only confirms a major prediction of Albert Einstein's General Theory of Relativity in its centenary year, but marks the birth of a whole new way to study the Universe.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the very fabric of the Universe.

They are produced by violent events out in the cosmos and are detected by sensing tiny local changes in the direction and strength of gravity here on the surface of the Earth.

This discovery is groundbreaking - for a number of reasons.

The gravitational wave detected has a fabulously precise signature - matching two black holes, which are each tens of times more massive than our Sun - spiralling into collide and merge.

It's the first time we've ever directly detected a pair of such black holes, and it's the first time we've seen the merger of black holes.

Until now these events were predicted but never before observed.

Perhaps most excitingly, this detection is our first direct message from the "dark" Universe. It has come from an event that might not give out light of any wavelength - one detectable only through changes in the gravitational field.

The technologies required had to be invented over the course of several decades

For decades after Einstein's 1916 prediction, gravitational waves were treated as a mathematical curiosity.

Only in the 1960s did the realisation come that they could be real, and the hunt for these elusive signals started in earnest.

Why did it take five decades and the intensive work of many hundreds of scientists around the world to find them?

Well, gravity is really very weak - the weakest of the forces that control our Universe.

So to detect these signals here on Earth requires instruments that are exquisitely sensitive to the tiniest changes in gravity and building them has been no mean feat.

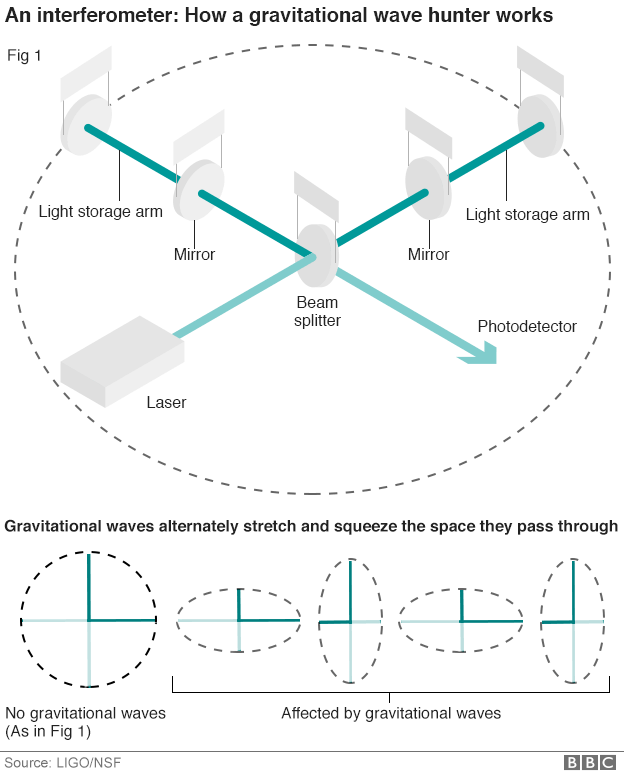

Gravitational wave detectors use a technique called laser interferometry.

A laser is beamed down km-scale pipes, arranged in an "L" shape to very precisely monitor the distance between mirrors at each end.

According to Einstein's theory, the distance between the mirrors will change when a gravitational wave passes by the detector.

The tricky part is that a gravitational wave changes the lengths of the arms by a tiny amount - about one-ten-thousandth the diameter of a proton.

Being able to achieve this required technology that didn't even exist 50 years ago - it had to be invented along the way.

A laser is fed into the machine and its beam is split along two paths

The separate paths bounce back and forth between damped mirrors

Eventually, the two light parts are recombined and sent to a detector

Gravitational waves passing through the lab should disturb the set-up

Theory holds they should very subtly stretch and squeeze its space

This ought to show itself as a change in the lengths of the light arms (green)

The photodetector hopes to capture this signal in the recombined beam

The current peak of technological achievement is embodied in the two Advanced LIGO detectors at sites in Louisiana State and Washington State in the US.

This is a major international project involving a consortium - the LIGO Scientific Collaboration - of nearly 1,000 scientists from countries around the world.

The UK, along with Germany, are partners in Advanced LIGO, with some of the key technology essential for this detection having been pioneered in the UK-German 'GEO' collaboration.

In particular, seismic motion of the surface of the Earth would naturally disturb the mirrors much more than any gravitational wave.

Sophisticated pendulums to hold the mirrors were developed at the University of Glasgow to combat this.

In these systems the mirrors hang from ultra-pure glass fibres just a few times thicker than a human hair.

This both filters out seismic noise and reduces noise from the very atoms of the mirrors vibrating, leaving the mirrors almost motionless and ready to respond to the gravitational echoes of colliding black holes, coming to us from more than a billion light-years away.

We also need to know what shape of signals to search for, and UK researchers in Cardiff have pioneered models to predict this, whilst scientists in Birmingham have studied how best to interpret the signals and understand what they tell us about the cosmic events producing them. All part of a global partnership.

Pallab Ghosh explains the sound of the gravitational wave and a computer visualisation

Most exciting is that this is just the start. More discoveries lie ahead - perhaps of colliding neutron stars - with rich new information about dense stellar interiors.

More sensitive detectors will expand our horizons towards the era of the early Universe, letting us map its gravitational history reaching back towards the Big Bang - further than ever before.

Future gravitational detectors in space - for which the recent LISA Pathfinder mission paves the way - should see supermassive black hole collisions of phenomenal energy.

Every time in history a new telescope has turned on it has found signals that were completely unexpected; perhaps that's the most exciting prospect of all.

The current peak of technological achievement is embodied in the Advanced LIGO detectors in the US