Tiny sea snail 'swims like a bee'

- Published

Blink and you'll miss it: the sea butterfly in action

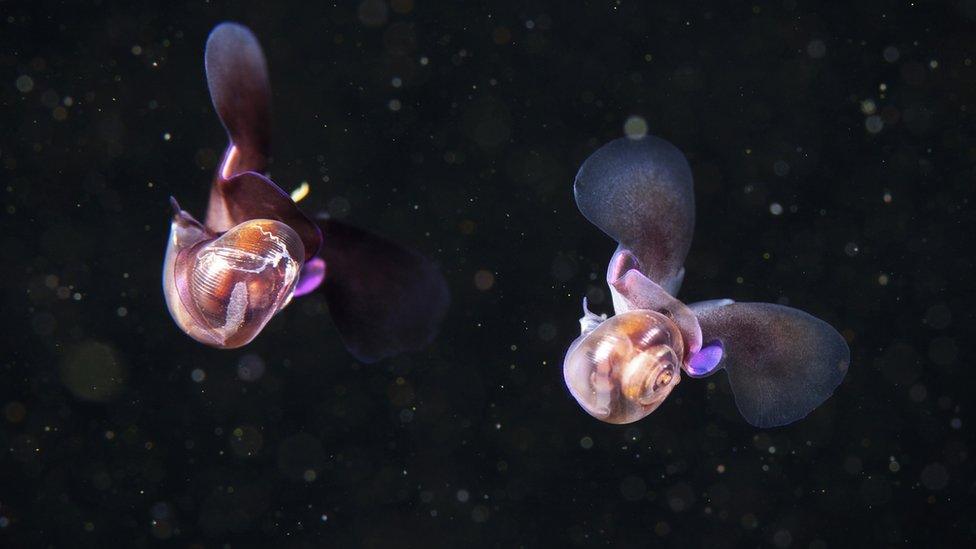

A tiny species of sea snail "flies" underwater using movements just like winged insects, according to a study.

US scientists observed the so-called sea butterfly - actually an aquatic snail - using high-speed video and flow-tracking systems.

The 3mm critter flaps its wing structures, which grow where a snail's foot would normally be, in a characteristic figure-of-eight pattern.

It also uses some of the vortex-making tricks that keep insects in the air.

"It looks like it's flying, like a very small insect," said Dr David Murphy, a mechanical engineer at Johns Hopkins University.

The study, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, external, was part of his PhD research while studying at Georgia Tech.

Honorary insect

Limacina helicina is a bizarre-looking predatory mollusc which, when not displaying its swimming prowess, makes large webs of mucus to filter-feed on smaller plankton.

Its insect-like acrobatics are "a remarkable example of convergent evolution", the researchers write. In other words, the same trait has evolved more than once in completely independent lineages.

Different types of sea butterfly range in size from 1-15mm

"Almost all zooplankton use their swimming appendages like paddles," Dr Murphy told BBC News.

"I was pretty sure that the sea butterfly was going to do something similar. But I was really surprised - it turns out to be more of an honorary insect."

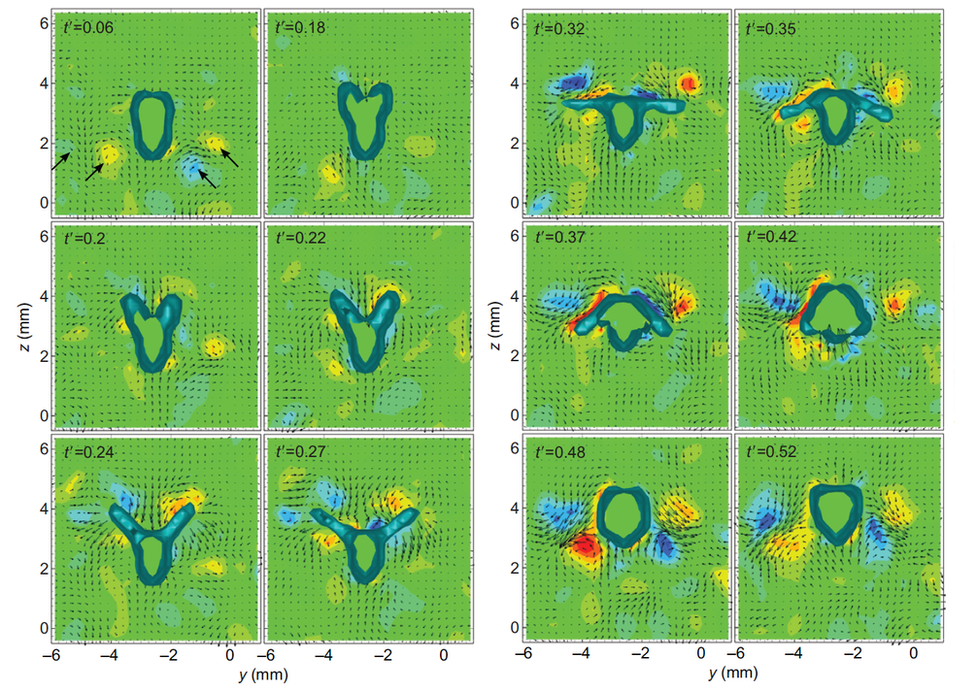

To make the discovery, Dr Murphy and his colleagues used a system they call tomographic particle image velocimetry: four high-speed cameras trained on a tiny volume of fluid, which is illuminated with laser beams and seeded with shiny particles to trace flow movements.

"Using our four cameras, we make a 3D measurement of the flow that the animal produces as it's swimming," he explained.

Four cameras traced exactly how fluid flows around the swimming snail

Simultaneously, the same system can track every detail of the animal's own movement.

"The 'aha' moment came when I'd spent a few months tracking the wing tips, relative to the body.

"I was putting all of this information into my code and finally it came out with this plot - and I saw this beautiful figure-of-eight pattern, which I immediately recognised as something more like what a fruit fly does."

Jelly in a shell

The similarity doesn't end there. The snail beats its wings with a similar, steep "angle of attack" to that used by insects, Dr Murphy said.

"And then what really convinced me, finally, was the flow information. It turns out they use one of the same tricks, to generate lift, that really tiny insects do."

This is a manoeuvre called the 'clap-and-fling': at the end of a stroke, the snail slaps its wings together behind its back, then pulls them quickly apart.

"This sucks fluid into that V-shaped gap as the wings open up, and creates tiny vortices at the tips of each of the wings. Those vortices are useful in generating extra lift."

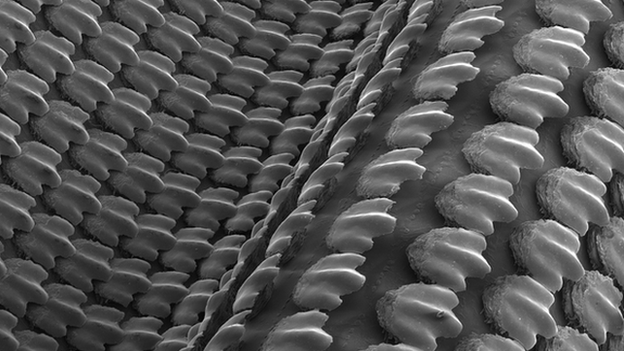

The creatures are entirely gelatinous, apart from a shell made of calcium carbonate

Understanding how these creatures get around, he added, will inform our knowledge of their behaviour in general - including how they find food, mates and avoid predators.

This is valuable because minuscule critters can play a big ecological role. The nightly migration of zooplankton, like Limacina helicina, to the ocean surface to feed and escape being eaten, is one of the biggest movements of biomass on the planet.

"They're also quite important in terms of bio-geochemical cycling; they have a shell made of calcium carbonate, so when they die and sink to the ocean floor this is an important carbon sink," Dr Murphy said.

And of course, like thousands of other animals with calcium carbonate shells, they are threatened by ocean acidification.

"They're actually quite difficult to study in the laboratory because they're incredibly fragile. They're essentially gelatinous, except for this shell.

"They're really quite a unique species."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published30 July 2014

- Published15 May 2014

- Published18 April 2013

- Published2 May 2013