Global food production needs 'significant' fertiliser boost

- Published

Production of grass will have to increase significantly to meet future demand for meat and milk

The world must significantly increase its use of phosphorus-based fertiliser to meet future demands for food.

That's the conclusion of a study that suggests a fourfold rise in the amount of mineral and organic phosphorus needed on grasslands by 2050.

The researchers say that at present, more phosphorus is being lost from soils than is being added by farmers.

But there are concerns that increases in the use of the mineral could damage the environment.

Phosphorus is an irreplaceable element for all life forms - but it is only since the 19th century that humans have been systematically using it to boost agricultural production.

The mineral can be mined as phosphate ore - but animal excrement is also an important source especially in the developing world.

Grass boom

Demand grew so rapidly over the 20th century that there were concerns about overuse and "peak phosphorus", external.

But research published in 2012, external, looking at the need for phosphorus on crops, suggested that future demand could be met from existing sources.

This new study though looks at the use of phosphorus on grasslands which cover around a quarter of the Earth's ice-free land areas.

These fields are crucial are in the production of milk and meat. As global incomes rise, demand for these products is set to soar. This in turn will spark a rise in demand grass crops and production is expected to increase by 80% by 2050.

But the study points out that at present, the vast majority of grasslands in the world are losing more phosphorus than they are gaining.

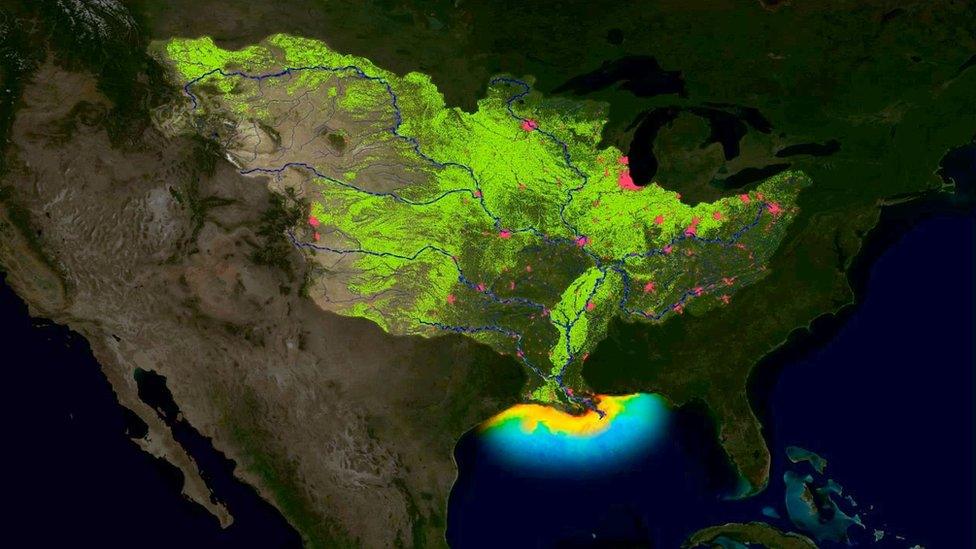

Phosphorus and other nutrients can create marine dead zones such as this one in the Gulf of Mexico

The losses are mainly caused by farmers collecting manure from grasslands and using it to fertilise croplands. The amount being lost from intensive farming is far greater than from pastoral systems. Between 1970 and 2005, 44% of these losses occurred in Asia.

"This is one main factor," said Prof Martin van Ittersum, a co-author of the study from the University of Wageningen in the Netherlands.

"Of all the manure that is deposited on the grassland, half of it is taken away for croplands or used for fuel or for plastering the walls of the houses in Africa. The fact is that the grasslands are not fertilised, so you have very little inputs to the system."

The researchers say that to meet the projected demand for grassland in 2050, the amounts of phosphorus used will have to grow more than fourfold from 2005 levels.

To cope with both grassland and arable land demands, the overall use of mineral phosphorus fertiliser must double by the middle of the century.

"It is a vast area but that is very significant, yes," said Prof van Ittersum.

"It is our strong assumption, that productivity will decrease and the pressure on our feed crops will increase and that is something that we should avoid," he said.

"There is already a societal concern that we are feeding too much of our cereal crops to livestock and that pressure will only increase if our grasslands decrease in productivity."

Marine impacts

But increasing the amount of phosphorus used on land, especially in mineral form, carries significant environmental concerns.

Excessive use of fertilisers of all types can lead to a leaching of nutrients into the sea where they have created so-called "dead zones", external.

"A fourfold rise in phosphorus use would have a big impact on the environment, especially on marine life," said Marissa de Boer who is European Project Manager of SusPhos, external at VU University in Amsterdam.

"The leaching of phosphorus from agricultural lands into rivers and eventually the sea leads to uncontrolled algae growth and dead zones such as the ones found in the Baltic Sea, Lake Erie and the Gulf of Mexico. This is an effect of increased fertilizer use in the past half century.

What would the effect be if we now increase phosphorus use fourfold?"

Prof van Ittersum says these issues can be controlled. The most important thing is awareness.

"We are still talking about modest amounts, I don't think the environmental risks are particularly big," he told BBC News.

"We have to do it carefully, we have to reuse our residues and wastes and make sure as little phosphorus as possible ends up in our sewage systems."

The study has been published, external in the journal, Nature Communications.

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external and on Facebook, external.