'Brain Prize' for UK research on memory mechanisms

- Published

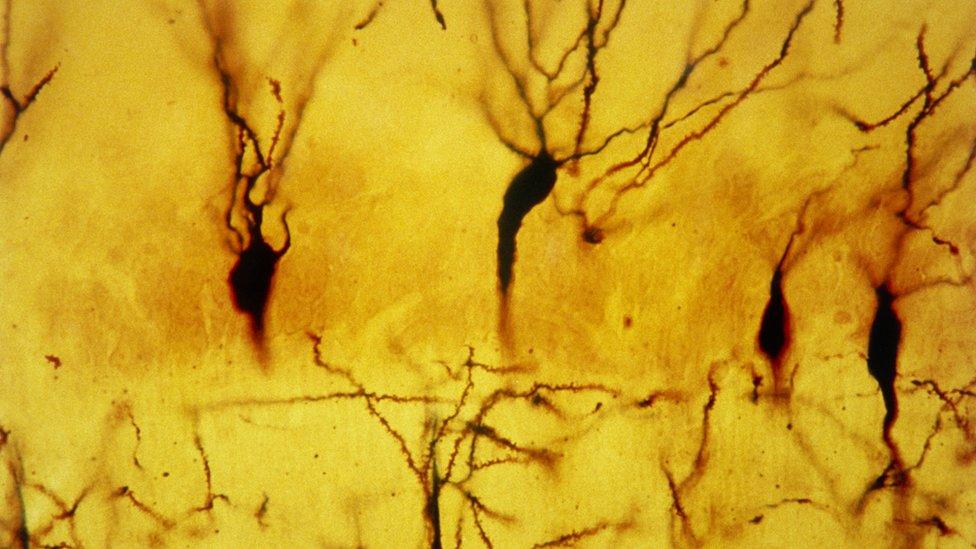

When a connection between two nerve cells is busy, it gets stronger

Three British researchers have won a prize worth one million euros, awarded each year for an "outstanding contribution to European neuroscience".

Tim Bliss, Graham Collingridge and Richard Morris revealed how strengthened connections between brain cells can store our memories.

Our present understanding of memory is built on their work, which unpicked the mechanisms and molecules involved.

This is the first time the Brain Prize, external has been won by an entirely UK team.

It is awarded by a Danish charitable foundation and the 2016 winners were announced in London on Tuesday.

Speaking to journalists at a media conference, Prof Morris explained it was the "chemistry of memory" that he and his colleagues had managed to illuminate.

Fire together, wire together

"Before this team got going, we had some idea about particular areas of the brain that might be involved in memory… but what we didn't have was any real understanding of how it worked," explained the professor, who works at the University of Edinburgh.

The "team" of three winners never worked together in the same laboratory, but they have collaborated over the years.

Prof Bliss (L) and Prof Morris spoke at a media conference, where the mood was celebratory

"Memories change the brain - the brain is plastic," said Prof Bliss, who worked for many years at the National Institute of Medical Research in London and is now affiliated with the Francis Crick Institute.

Those changes occur at the junctions between nerve cells - synapses - and were described in a pioneering study, external by Bliss and a Norwegian colleague, Terje Lømo, in the 1970s.

They recorded brain cells in anaesthetised rabbits and found that repeatedly stimulating two connected neurons caused their connection to get stronger.

"If nerve cell A is connected to nerve cell B, and A takes part in firing B, then the synapse - the connection between A and B - will be strengthened," Prof Bliss explained.

This paradigm, sometimes summarised as "neurons that fire together, wire together", was suggested by the Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb in the 1940s, but Bliss and Lømo were the first to glimpse it happening inside the brain.

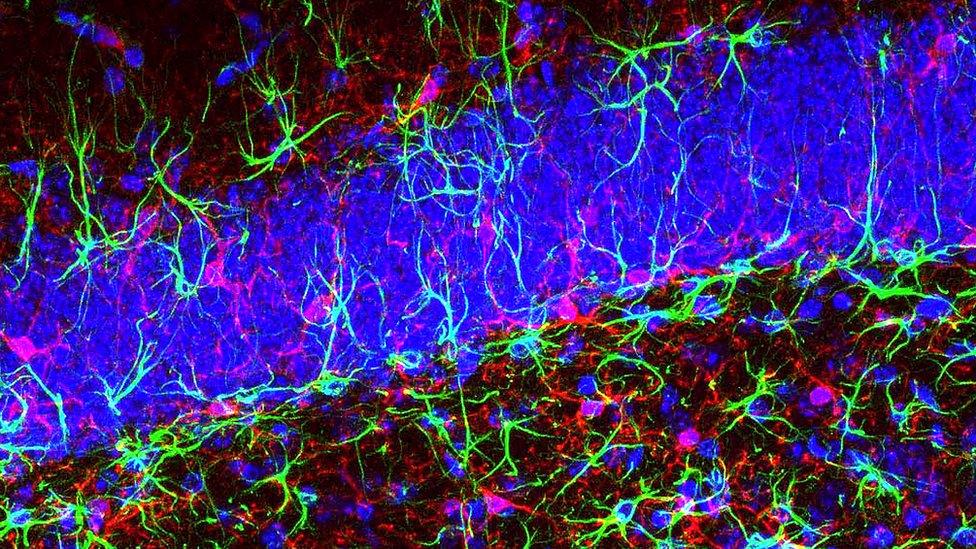

Subsequently, Prof Collingridge - a researcher at the University of Bristol - worked on finding the specific molecules responsible.

Currently working at the University of Toronto in Canada, he spoke to journalists by telephone and paid tribute to the original Bliss and Lømo study.

Their paper was an inspiration to him as a young researcher, Prof Collingridge said.

"I immediately recognised that this was a phenomenally interesting property, which gave us the opportunity to understand the mechanisms of learning and memory in the brain - and decided that this was going to be my career."

Finally, it was Prof Morris who demonstrated that the molecular systems identified by Prof Collingridge and his colleagues were, in fact, crucial for memories to form.

If those systems are disrupted, for example, rats and mice have difficulty learning to navigate a new environment.

The most critical connections are made in part of the brain called the hippocampus

The Brain Prize is awarded by the Grete Lundbeck European Brain Research Foundation, based in Copenhagen; a committee, external of eight neuroscientists makes the decision.

Billed as "the world's most valuable prize for brain research", its one million-euro value - to be shared by the three winners - marginally exceeds that of the biennial US $1m neuroscience prize awarded by the Kavli Foundation, external.

It will be presented in Copenhagen on 1 July by Denmark's Crown Prince Frederik.

The first British winner was geneticist Prof Karen Steel of King's College London, who shared the prize in 2012 for her work on deafness; Cambridge psychologist Trevor Robbins was one of three recipients in 2014.

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published5 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published17 March 2015

- Published6 October 2014

- Published8 July 2014