Ancient DNA identifies 'early Neanderthals'

- Published

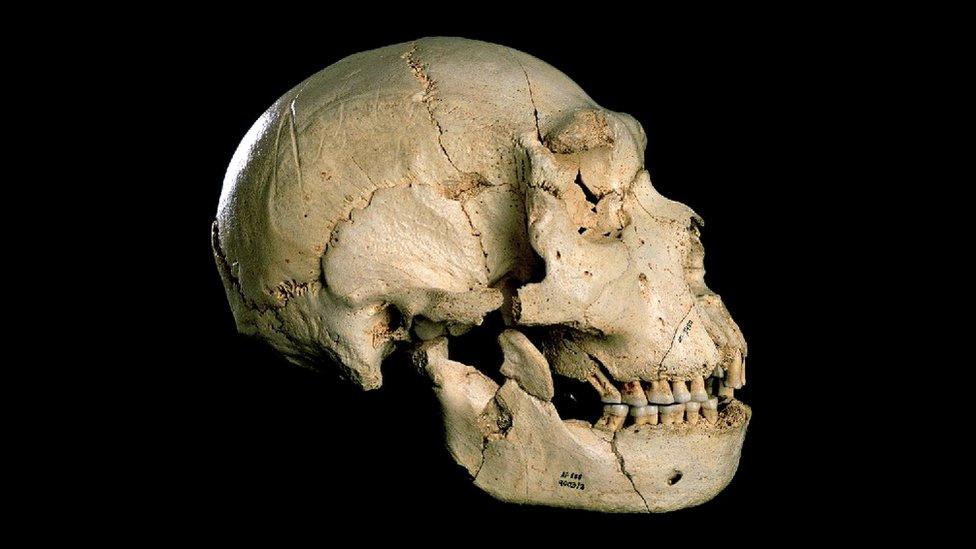

The relationship of the Pit specimens to other ancient species has been the subject of debate

The oldest "nuclear DNA" from a human has identified some early representatives of the Neanderthal lineage.

The well-preserved ancient remains from the "Pit of Bones" site in Spain have been known for more than three decades.

They are about 400,000 years old, but their relationships to Neanderthals and other ancient relatives has been hotly debated.

DNA analysis confirms that they lie on the evolutionary line to Neanderthals.

The results are published in the journal Nature, external.

Nuclear DNA accounts for most of the instructions to build an organism, and is located in the nuclei of our cells.

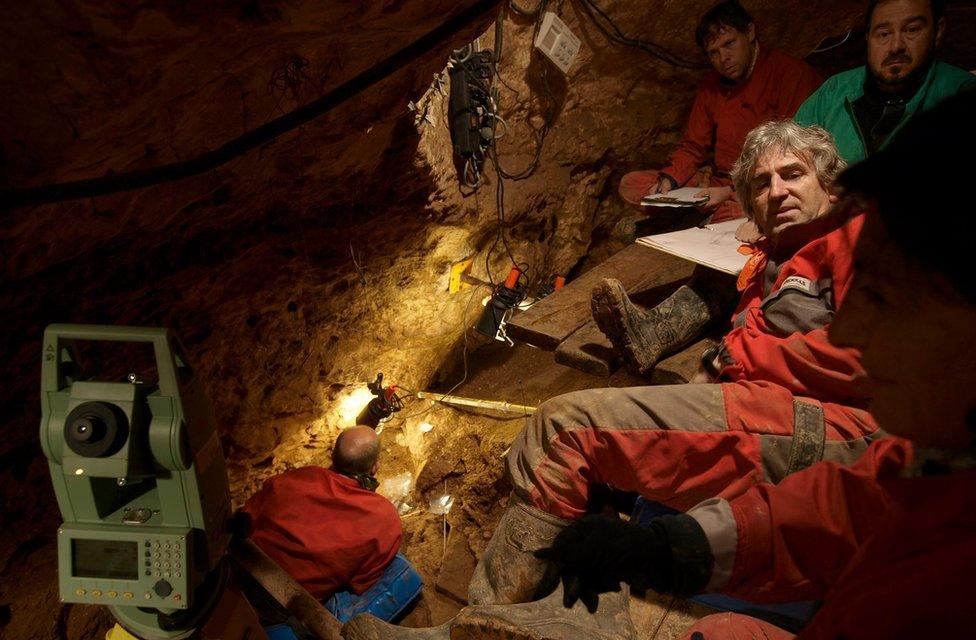

The 13m-deep shaft has been carefully excavated over the past three decades

Analysis of DNA from specimens this old is very challenging. But owing to the careful way the bones were excavated, and advances in genetic sampling and sequencing technology, the team was able to reconstruct parts of the genomes from a tooth and a thigh bone found in the pit.

However, this was enough to reveal their evolutionary affinities.

Based on skeletal evidence, the 28 individuals buried in the 13m-deep cave shaft have been variously interpreted as belonging to a human species called Homo heidelbergensis or as proto-Neanderthals - that is, on their way to evolving the classic physical characteristics of the Neanderthals.

But in 2013, a team reported their analysis of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) retrieved from remains at the archaeological site - known as Sima de los Huesos in Spanish. This type of genetic material is inherited only via the maternal line.

They concluded that the mtDNA was more closely related to that found in the enigmatic Denisovans, external, a population of ancient humans who inhabited Asia more than 50,000 years ago, than to that found in Neanderthals.

Bone powder from a thigh bone yielded the first DNA sequences from the 430,000-year-old hominins

The Denisovan link was a surprise, especially given the Neanderthal-like characteristics of the bones.

But the latest genetic results reveal that the Pit of Bones people were indeed closely related to the Neanderthals.

"Sima de los Huesos is currently the only non-permafrost site that allows us to study DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene, the time period preceding 125,000 years ago," says Matthias Meyer of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

Juan-Luis Arsuaga, from the Complutense University in Madrid, who led the excavations at Sima de los Huesos, said: "We have hoped for many years that advances in molecular analysis techniques would one day aid our investigation of this unique assembly of fossils"

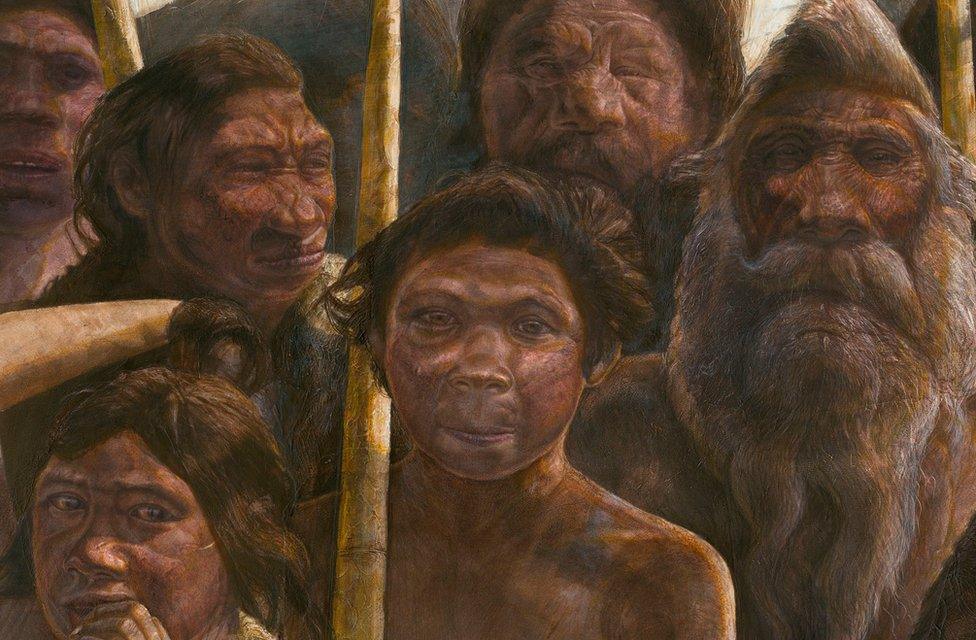

This artist's impression shows what the Pit of Bones people might have looked like

"We have thus removed some of the specimens with clean instruments and left them embedded in clay to minimise alterations of the material that might take place after excavation."

Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA from one individual supported a relationship to Denisovans - consistent with the previous study.

This leads the scientists to speculate that mitochondrial DNA types seen in later, "classical" Neanderthals may have arrived in a migration from Africa, replacing those present in the Pit of Bones people.

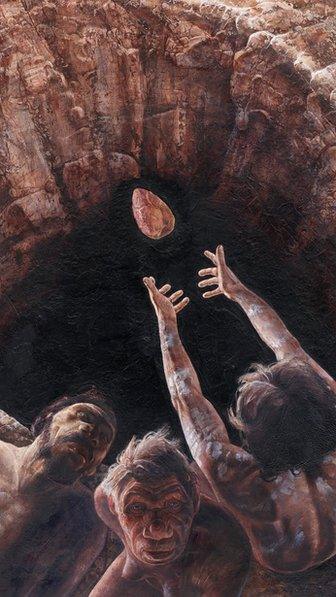

It's unclear whether the remains came to rest in the pit accidentally, or were deposited there as part of ritual burial

Prof Chris Stringer, from London's Natural History Museum, who was not involved with the latest study, said the results shed new light on how our own species (Homo sapiens) and Neanderthals diverged from a common ancestor.

"There has been continuing debate about how deep in time the Neanderthal-sapiens split was, with estimates ranging from about 800,000 years to 300,000 years," he explained.

"I have recently favoured a split time of about 400,000, and have argued for many years that the widespread species H. heidelbergensis at about 500,000 was probably their last common ancestor."

He added: "When new genetic data are used to recalibrate divergence times, these now suggest older split times both between the Neanderthals and Denisovans (approximately 450,000 years) and their lineage and ours (approximately 650,000 years)."

Prof Stringer said research must now refocus on fossils from this key time interval to determine which ones might actually lie on the respective ancestral lineages of Neanderthals, Denisovans and modern humans.

Co-author Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology commented: "These results... are consistent with a rather early divergence of 550,000 to 750,000 years ago of the modern human lineage from archaic humans."

How the skeletons of 28 ancient people, along with the remains of prehistoric animals, ended up at the bottom of the pit is unknown. They might have fallen to their deaths through an opening, but some experts think they were deliberately buried.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external