Giant web probes spider's sense of vibration

- Published

Watch the giant web in action

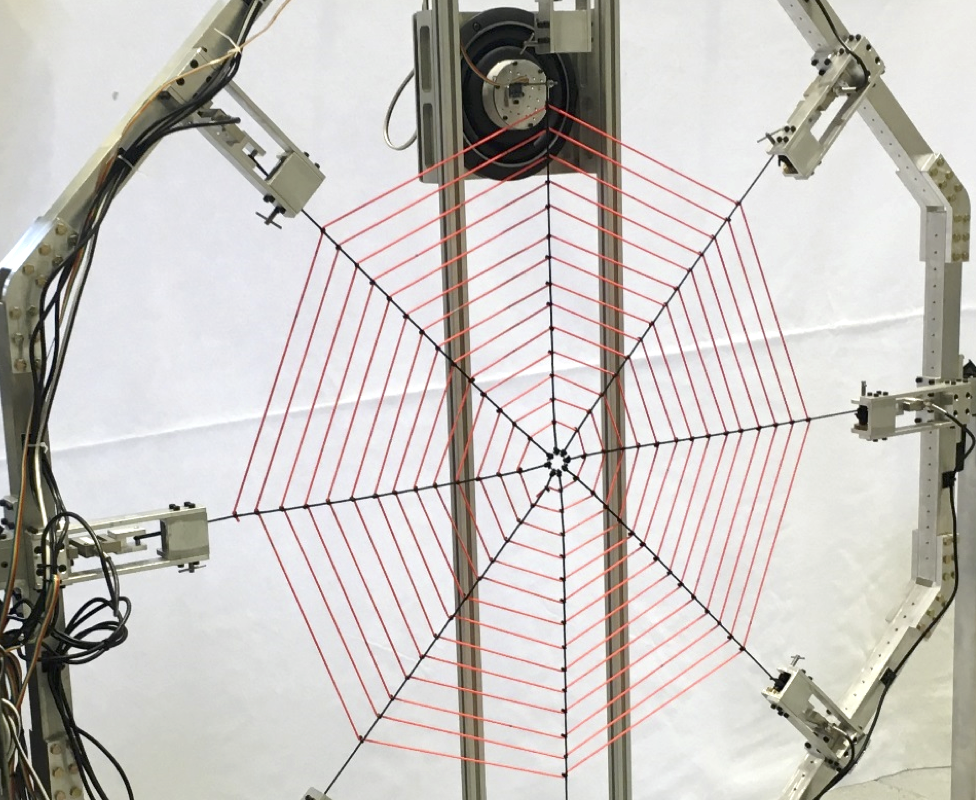

Inside a lab in Oregon, US, a two-metre spider web made of aluminium and rope is beginning to unlock how orb weavers pinpoint struggling prey.

When an unlucky insect lands in a web, it is vibrations that bring the spider scuttling from the centre of its trap.

How spiders interpret those signals is a mystery - so physicists have built this replica to figure it out.

They unveiled the design and their first results on Friday at a meeting of the American Physical Society, external (APS).

"We wove the web using two different kinds of rope, the same way as spiders use two different formulations of silk," said Ross Hatton, external from Oregon State University.

The radial strands that fan out from the centre are made of stiff, nylon parachute cable, while elastic bungee cords make up the "spiral strands".

The whole thing sits in an octagonal aluminium frame, with a speaker strapped to one corner to deliver some hefty vibrations.

A subwoofer hits the web with specific frequencies

"It's a big subwoofer, so we can give a fairly good push to the web - there's quite a bit of force in it," Dr Hatton told BBC News, at the APS March Meeting in Baltimore.

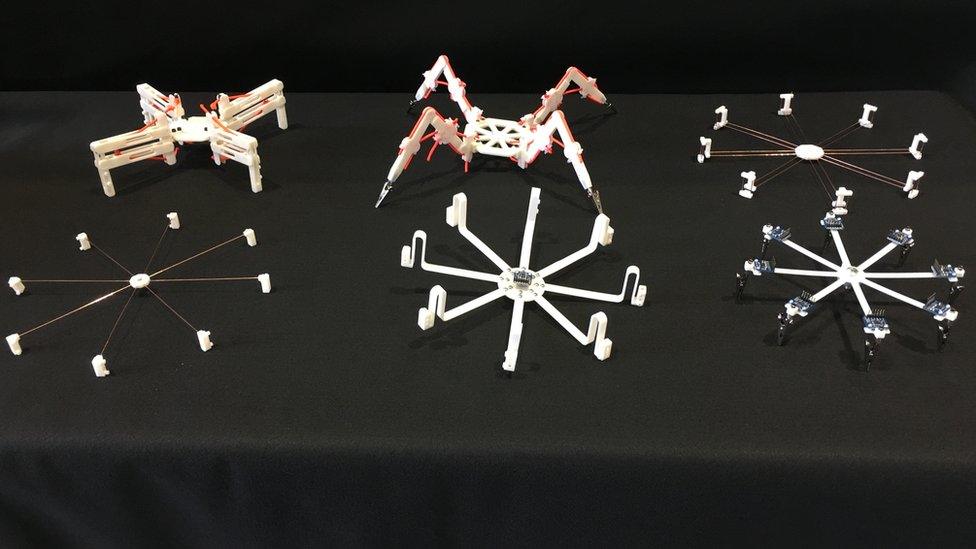

At the centre of the web sits an artificial spider - a simple eight-legged frame, which doesn't move but detects vibrations in the threads, just like a real spider.

"We went in with the basic hypothesis that if you shake one of the radial lines, then the spider will feel that shaking a lot, and the other lines less," Dr Hatton explained. "And so you could say, well I just go to wherever the line is shaking the most."

But this was not what he and his colleagues - including biologist Damian Elias, external at the University of California Berkeley - discovered.

The team has a selection of "spiders" to use for different experiments

In fact, the outsized orb web revealed surprisingly complex vibration patterns, with quiet spots in certain parts of the web where the shaking completely disappears.

"At different frequencies, different strands - so different feet - stop vibrating," Dr Hatton said.

Those different frequencies might reflect, for example, different types of trapped insect.

"So at the very least, the spider is going to need to know how the frequency couples with the web structure... in order to find which is the foot that shouldn't be shaking - so it doesn't end up going off at 90 degrees to where it should be going."

Follow Jonathan on Twitter, external

- Published23 May 2015

- Published11 December 2014

- Published26 November 2015

- Published7 March 2012