Can 'pay as you glow' solve Malawi's power crisis?

- Published

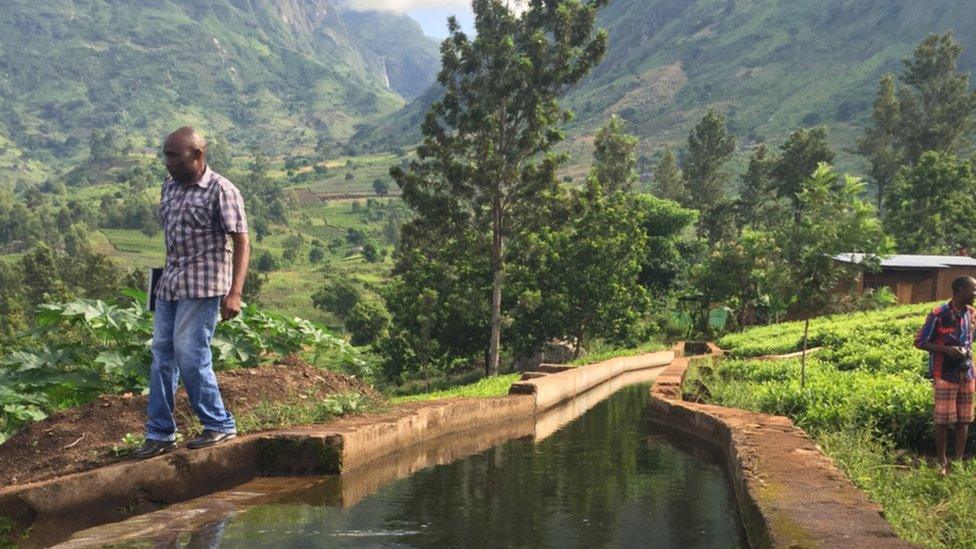

This canal feeds a small-scale hydro scheme in the village of Bondo, Malawi that powers 250 homes

Two months ago, Bill Gates reminded us, external of a stunning bit of information.

The amount of electricity per person in sub-Saharan Africa is lower today (excluding South Africa) than it was 30 years ago.

A rapidly rising population and the slow rate of connection means the "electricity deficit" continues to grow.

Even having a connection is not a guarantee of power.

All across the continent you can hear phrases like "dumsor", "kuzima zima", and even the slightly dubious "rolling brownout".

These curious terms all refer to the on-again, off-again "load shedding", external process, where electricity is rationed to cope with overwhelming demand.

For the sad truth is that there is often more of the mythological "electricity in the air" in Africa than there is in the wires strung between generating stations, homes and offices.

In Nigeria, according to the Afrobarometer survey, external, 96% of the population are connected to the electrical grid, but only 18% can expect the service to work most of the time.

Further south in the continent the picture is often worse.

Malawi is a beautiful, verdant slip of a country, wedged in between Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia.

Despite its natural resources and tourism potential, the nation is better known for coming close to the bottom of some important global league tables, external, such as income per capita.

Malawi’s verdant countryside makes it an attractive tourist destination but hotels often suffer from “load shedding” power cuts

When it comes to electricity connections, Malawi is a classic example of how not to do it.

Roughly 9% of the population are connected to the grid - in rural areas, this falls to about 1%.

The population is growing about 3% a year, meaning that every year the country is falling further and further behind.

The state utility, Escom, produces most of its grid power from hydroelectric installations on the Shire river. But falling water levels have hampered the reliability of this source.

To try and get more people on the grid the government is opening up the energy market to independent producers.

Power at a price

I visited Malawi to investigate the impact that lack of electricity was having on people's lives for BBC Newsday.

According to Malawi's Energy Minister, Bright Msaka, this opening up of the market will make a significant difference.

Women about to give birth at Milonde health centre have to bring their own lighting with them, usually candles or torches

Mr Msaka told me that Malawi would produce an extra 200MW of solar energy by 2019.

That's a big claim for a country that at present has a total installed capacity of less than 300MW from all sources. However, if this improvement in supply does actually materialise, it will come at a price.

"We have to make sure that the people who come to invest in the power sector in Malawi are able to make a profit," Mr Msaka said.

"Either you have cheap power that is inadequate or you have adequate power for which you pay the appropriate price."

The idea of paying significantly more for electricity is not good news for people in villages like Milonde.

The medical centre doesn't have electricity. Vaccines are stored in a fridge powered by bottles of gas.

When the gas runs out, the vaccines have to be physically taken to another health centre 20km away, then brought back when the fridge is working again.

Candles are considered a dangerous and ineffective form of lighting but women in many maternity units have no choice

On a thunderous afternoon, I watched 50 secondary school students, crammed into a dank, dark classroom trying to complete an exam under the light of a single solar powered bulb.

But while small-scale solar might not be the solution in a large classroom, for millions of people in Malawi and elsewhere it could prove to be an important, intermediate step on the road out of darkness.

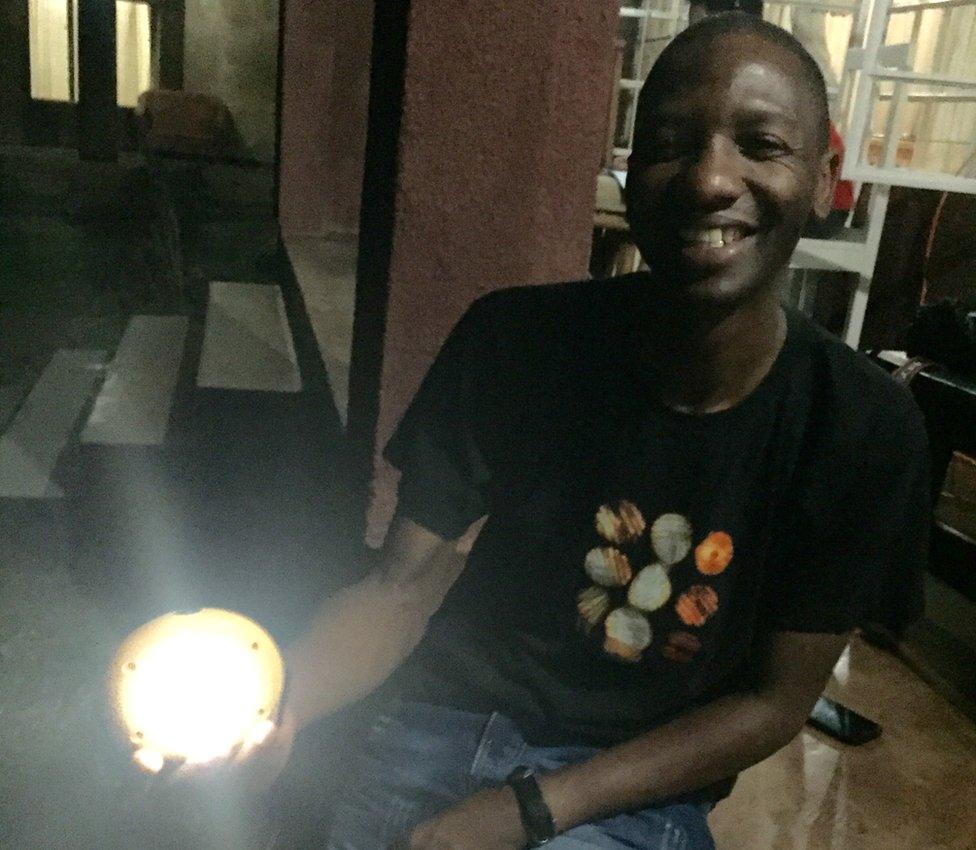

Brave Mhonie certainly believes that cheap, solar lights are perhaps the only way forward for the rural poor.

Brave is the national sales co-ordinator for SolarAid, external, a charity which sells solar-powered lights that also charge mobile phones.

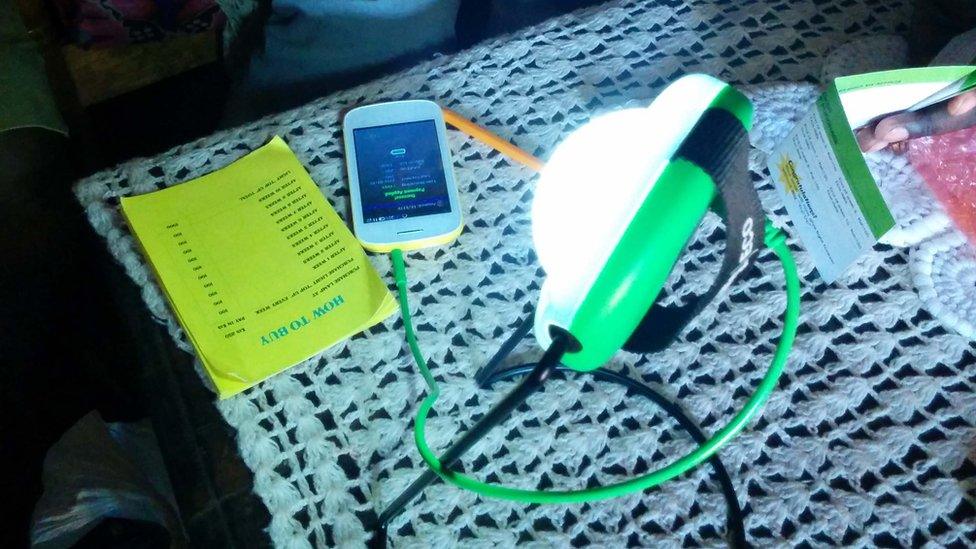

A pay-as-you go solar lamp takes eight hours to charge but can give light for 30 hours

They've introduced a pay-as-you-go ownership scheme for these lamps, which cost about $12 (£8).

That's a lot of money in a country where people typically earn about a dollar a day. So the company charges $3-$4 upfront, and the rest is paid off over time.

"We tell customers how much the lamp costs and we ask them to pay over three to four months, but if they don't pay the lamp goes off," says Brave.

"The amount of light that you get is linked to the amount of money you pay."

The solar lamps can also charge mobile phones

If the customer defaults on a payment, the distributor enters the details on his phone which is linked to the lamp and the lights go out. A high-tech solution to a low-tech problem.

Network of teachers

So far the "pay as you glow" model is working well as the amount people pay monthly is roughly the same as they would spend on paraffin lamps.

In Malawi, even the remotest and poorest areas have schools - SolarAid takes advantage of that network to distribute their products.

And headteachers make fantastic intermediaries.

"We know we are the agents of change and people use us to get the information on solar lights," said Prosper Zilima, who runs a school with 1,200 pupils.

"We teach them how important these solar lamps are, in terms of saving money and in terms of fire risk from the paraffin lamps."

Students at Milonde secondary school in Malawi at morning assembly – a lack of connection to the electricity grids means they have no laboratory for science lessons

People in these areas trust the teachers, who collect the money and place the orders. The heads also get a little commission that boosts their own salaries. Most buy solar lamps for themselves as well as selling them to the local population.

"I have four lamps and they are assisting me fully," said Simeon Namakhwa, another teacher with a large school.

"Even my kids are studying using these type of light lamps - I don't use money for paraffin or candles because of these lamps, but I have a full night of light."

These may seem like small steps and indeed they are - but solar is scalable and a single lamp today can be added to until a whole home is lit up.

With mobile phone networks covering over 80% of the continent, electric power is more than ever the most important key to helping rural poor people take advantage of the connection and become better educated, informed and prosperous.

While African governments dither over reform of utilities and investing in large-scale power plants, the little solar lamp approach may just be the critical breakthrough for millions of people

The future of electric light in Africa may not be that bright, in fact it's likely to be quite dull - but that slowly dawning glow of solar power could mark real, sustainable change across the continent.

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external and on Facebook, external.

- Published15 March 2016