DNA points to Neanderthal breeding barrier

- Published

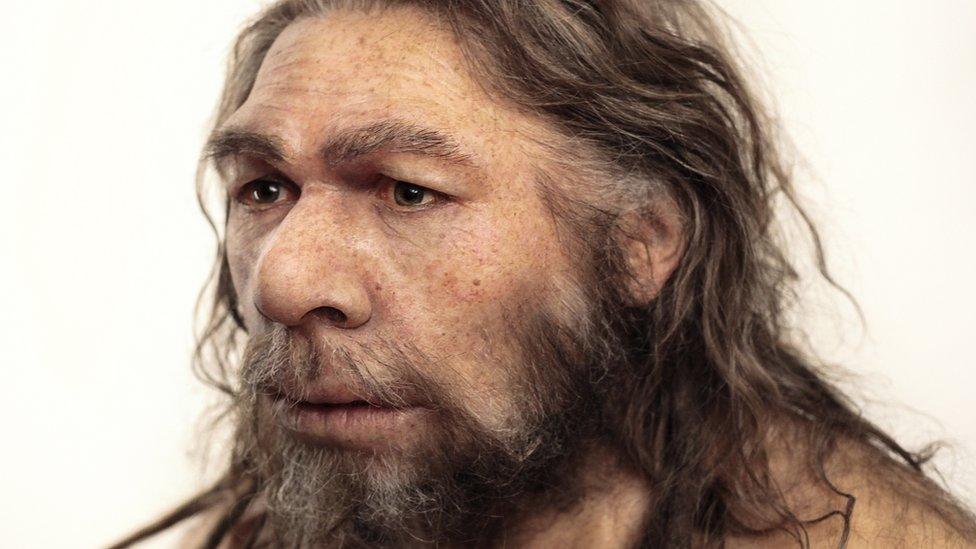

Reconstruction of a Neanderthal male

Incompatibilities in the DNA of Neanderthals and modern humans may have limited the impact of interbreeding between the two groups.

It's now widely known that many modern humans carry up to 4% Neanderthal DNA.

But a new analysis of the Neanderthal Y chromosome, the package of genes passed down from fathers to sons, shows it is missing from modern populations.

The team found differences in immunity genes on the Neanderthal Y chromosome that could have led to miscarriages.

The results have been published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, external.

The small amount of DNA in present-day people is the legacy of breeding between the two populations 50,000 years ago - after our species Homo sapiens expanded out of its African homeland and began to colonise Eurasia.

But the new analysis reveals the Neanderthal Y chromosome is distinct from any found in humans today.

"We've never observed the Neanderthal Y chromosome DNA in any human sample ever tested," said co-author Prof Carlos Bustamante, from Stanford University in California.

"That doesn't prove it's totally extinct, but it likely is."

The researchers say it is possible that Neanderthal Y chromosomes were initially circulating in the modern human gene pool, but were then lost by chance over the millennia.

Another possibility is that they included genes that were incompatible with other genes found in modern humans. Indeed, the researchers found evidence to support this idea.

Several of the Y chromosome genes that differ in Neanderthals function as part of the immune system. Three are "minor histocompatibility antigens," or H-Y genes, which resemble ones that transplant surgeons check to make sure that organ donors and organ recipients have similar immune profiles.

Because these Neanderthal genes are on the Y chromosome, they are specific to males.

In theory, a woman's immune system might attack a male foetus carrying Neanderthal versions of these genes. If women consistently miscarried male babies carrying Neanderthal Y chromosomes, that would explain its absence in modern humans.

So far this is just a hypothesis, but the immune systems of modern women are known to sometimes react to male offspring when there's genetic incompatibility.

Prof Bustamante said: "The functional nature of the mutations we found suggests to us that Neanderthal Y chromosome sequences may have played a role in barriers to gene flow, but we need to do experiments to demonstrate this and are working to plan these now."