Solar Impulse: A repaired plane and team

- Published

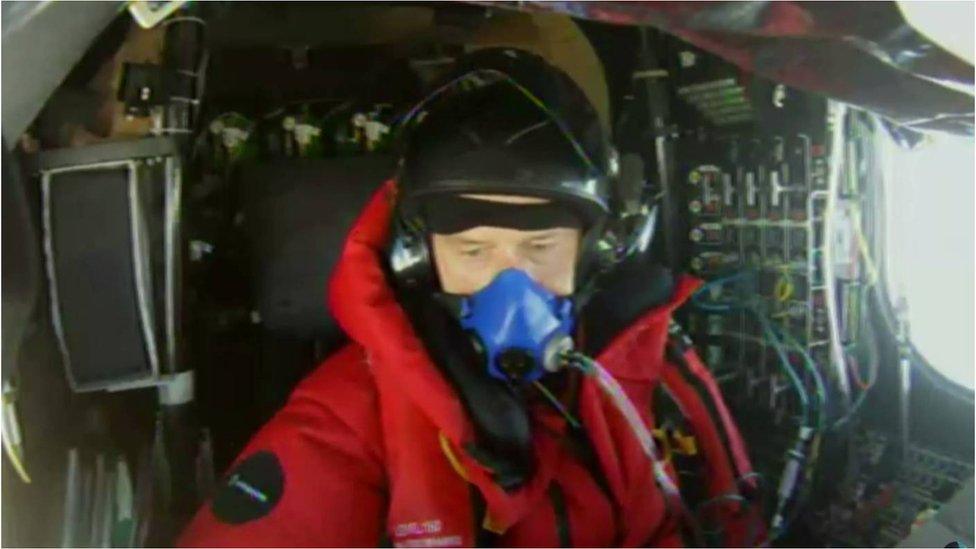

Andre Borschberg: "I felt the situation was very difficult and very emotional"

All big projects have their crunch moments, and these pinch points will very often define the people involved.

For the Solar Impulse team, external it came over the northern Pacific Ocean in mid-summer last year.

Their pilot Andre Borschberg was in the midst of trying to make a crossing from Japan to Hawaii - the longest non-stop solo aeroplane flight in aviation history.

Although a routine journey for today's airline passengers, this 8,000km passage was full of uncertainty and danger for the Swiss adventurer's slow-moving, sun-powered vehicle.

Did it have the performance? Did he, on what would be a five-day and five-night feat of endurance?

And Andre had a major problem: one of his key safety systems wasn't working.

Raymond Clerc (extreme right) leads the team in mission control in Monaco

This was the electronic box he calls his "virtual co-pilot".

It's a system that monitors the plane while the human pilot rests, and will sound the alarm if the craft starts to do something it should not.

For the super-light Solar Impulse plane, easily buffeted by winds, a potentially disastrous situation could arise at anytime. The experienced hand of the aviator needs to be available to take control in the instant - something that would be delayed if he is in a deep slumber.

And so to proceed with continuous flight for several days and nights without this critical back-up seemed a risk too far.

At least that's what many of the team's engineers at mission control in Monaco thought. They wanted Andre to abort the crossing and turn back to Japan. He, on the other hand, intended to press on. And that led to quite a bust-up.

"The weather window was constantly improving and I thought if I looked at the global risk of the situation this was a good window and I could manage the deficiency I had, and I decided to continue.

"But it was a drama because some of the engineers threatened to resign immediately as they did not understand my decisions," he told me.

"This was the first time for a dramatic and extremely important decision that we were not unanimous.

"I felt the situation was very difficult and very emotional. The technical decision for me was easy because I was prepared for that, but the emotional side of it was extremely strong, and I meditated the entire night. And when I saw the sun rise in the morning, I had the feeling I could throw these emotions out of the cockpit and really get into the flight."

The plane has been undergoing repairs in Hawaii and is now ready to complete its global journey

Bertrand Piccard watches from the Hawaii runway as Andre Borschberg takes a training flight

The disagreements were resolved in a clear-the-air teleconference between the cockpit and mission control. But the drama left its mark on the dynamics of the team.

Fortuitously, as Andre now views it, the plane suffered damage to its batteries on the Pacific crossing, which meant it had to undergo some lengthy maintenance. It was an opportunity also to repair the team.

"We called in a friend of mine who is a captain with EasyJet," recalls Solar Impulse flight director Raymond Clerc.

"He is a trainer in that company for what we call CRM - Crew Resource Management.

"Each airline pilot has to do this every year. It's about improving communication between different teams. It's an approach used now in hospitals and police forces, and the like, but it came out of aviation.

"It was realised in the 70s and 80s that a lot of accidents were due to misunderstandings within the cockpit, for example between the captain and the co-pilot. You can have a very good aircraft but you can crash because the people do not understand each other.

"So we've done sessions with the engineers and the pilots, in the "classroom", and I think it's had a good effect."

Andre likens the sessions to "couples therapy".

What has emerged, he believes, is a more solid team, a stronger unit - one that will be better able to deal with any future crises.

Solar Impulse now stands ready to try to complete its circumnavigation of the globe.

Last year, it travelled from Abu Dhabi, UAE, to Kalaeloa, Hawaii. If the weather is kind, the plane will seek to fly to the US West Coast in the coming days.

Andre's business partner and project chairman, Bertrand Piccard, will be at the controls for the first leg, which will aim for one of Phoenix, Los Angeles, San Francisco or Vancouver.

The hope is to be in New York in June to begin preparations for an Atlantic crossing. If Solar Impulse gets that done successfully, it should be a relatively straightforward run to the finishing line in Abu Dhabi.

"Before the flight from Japan there was still a very big question mark," says Andre. "Would we be able to do it? Would the airplane be capable? Would we have enough performance? And of course this is now done; it has been demonstrated, and we go to the next leg with a high level of confidence.

"It's still not easy because the weather is not totally predictable. But the longest flight we needed to do is done. So from an exploration point of view and a technical point of view, I think we are in a very good position."

LEG 1: 9 March. Abu Dhabi (UAE) to Muscat (Oman) - 772km; 13 Hours 1 Minute

LEG 2: 10 March. Muscat (Oman) to Ahmedabad (India) - 1,593km; 15 Hours 20 Minutes

LEG 3: 18 March. Ahmedabad (India) to Varanasi (India) - 1,170km; 13 Hours 15 Minutes

LEG 4: 18 March. Varanasi (India) to Mandalay (Myanmar) - 1,536km; 13 Hours 29 Minutes

LEG 5: 29 March. Mandalay (Myanmar) to Chongqing (China) - 1,636km; 20 Hours 29 Minutes

LEG 6: 21 April. Chongqing (China) to Nanjing (China) - 1,384km; 17 Hours 22 Minutes

LEG 7: 30 May. Nanjing (China) to Nagoya (Japan) - 2,942km; 1 Day 20 Hours 9 Minutes

LEG 8: 28 June. Nagoya (Japan) to Kalaeloa, Hawaii (USA) - 8,924km; 4 Days 21 Hours 52 Minutes

- Published15 July 2015

- Published3 July 2015

- Published2 July 2015